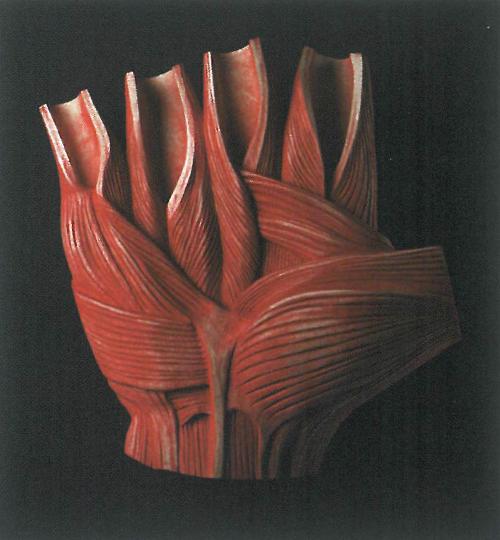

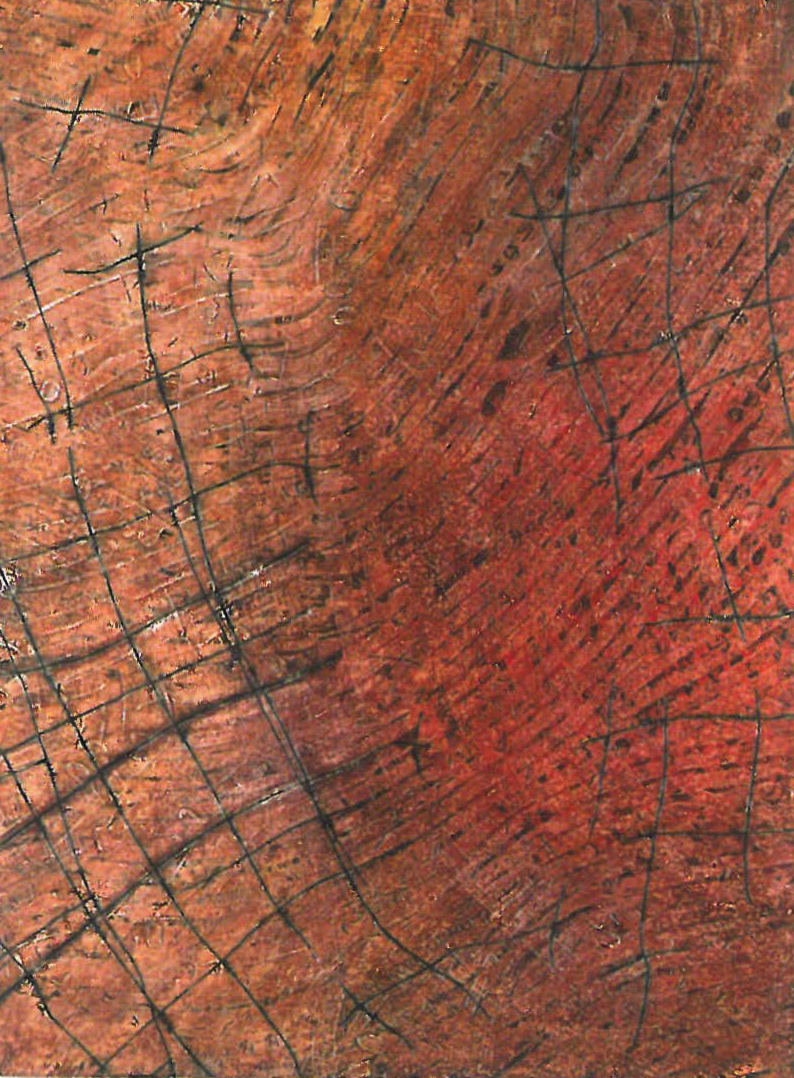

Wendy Teakel's landscapes begin with a baptism of fire. Adapting the technique of pokerwork, she uses heated strands of fence wire or fragments of found metal to sear cartographic designs on sheets of plywood, canvas and stretched paper. Later she applies acrylic paint, bringing colour and a sense of contour to these aerial views. But the initial interplay of scorched tracks and charred furrows remains visible in the finished work.

The act of burning suggests natural cycles of destruction and regrowth. The exhibition title, Drought and Fire, indicates that contemporary concerns about climate change and bushfire are being chronicled. In developing this theme, the works on paper are especially resonant. Washes of diluted paint have stained the paper in weathered tones of ochre, ash and rust. Signs of erosion suggest a countryside in decline, but the feeling is neither maudlin nor sententious. The layering of media and the transparency of process successfully evoke the long sequence of accretions (physical and cultural) that give depth of meaning to the experience of place.

There are encouraging signs that landscape is enjoying something of a rejuvenation in contemporary art. John Wolseley's recent shows, the continuing success of Mandy Martin and this exhibition by Teakel are part of a broader trend. It is anything but a return to cows and gum trees but rather a highly literate engagement, informed by history, science and readings from a growing literature that might be described as philosophy of place.

These highly contemporary landscapists take an innovative approach to process, achieving synthesis between their subject and the finished work. Wolseley, for instance, has been drawing images of bushfire damage by means of a highly gestural process that involves dragging sheets of paper through the charred bushland he depicts.

Teakel approaches the country near her home outside Canberra in an almost archaeological manner. Repeated visits to a farm near the town of Hall provide opportunity for observation and for the collection of materials: corrugated iron, old guttering and feeding troughs - uniquely coloured by peeling paint or deterioration of the galvanised coating. Often used in conjunction with organic material like oats and grass, coils of wire mesh and sheet metal provide material for her sculptural works.

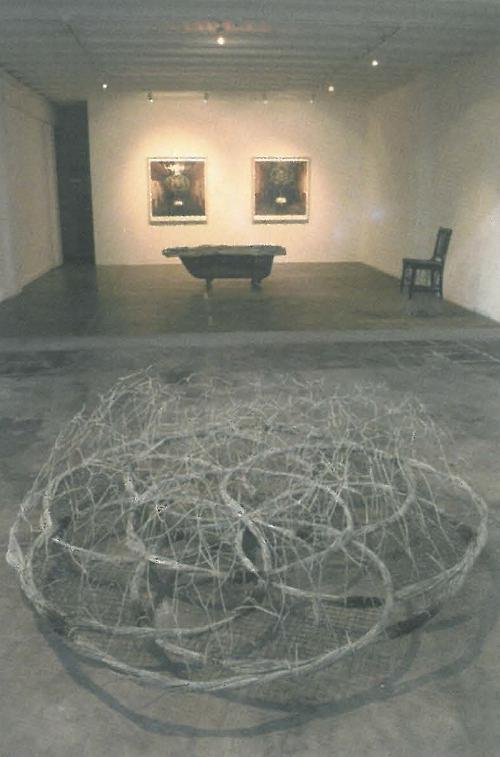

The combination of two and three-dimensional objects was a particularly persuasive aspect of Drought and Fire. Two floor sculptures, both waist-high, consisted of gutter-like troughs supported by plinths of wire mesh. They directed movement through the gallery and drew attention to the materiality of the subject. The troughs were filled not with water, but with oats, salt, tea and sugar: human foodstuffs arranged in bold patterns.

Fixed to a wall was Wind, another, far more delicate, sculpture. An imaginary form crafted from fine chicken wire, it seemed organic in inspiration, though it reminded me of a dilly bag or fish trap, the opening of which was fringed with tufted grass.

Such imagery alludes to Aboriginal technologies and traditions - an association reinforced by Teakel's preference for the aerial perspective in her two-dimensional landscapes. Formally there is a certain commonality with dot and acrylic paintings, though the iconography is completely her own. Being interested in land use history, indigenous and non-indigenous, it is inevitable that intimations of Aboriginal presence can be felt in Teakel's complex landscapes.

Perhaps such presence is registered in the opening gambit that produces the drawings and paintings. The pokerwork is a form of inscription that could destroy the paper if it is not applied with lightness of touch. Here is a consummate metaphor for travelling lightly. It also evokes Aboriginal traditions of 'firestick farming' - the burning practice that gave to Australia its distinctive ecological form.