In recent years the word 'craft' has developed negative and dowdy associations compared to its sexier siblings 'contemporary art' and 'design'. The very sexiest areas of contemporary art and design are those that espouse a connection with science and advanced technology. In her claim that the three craft practitioners in Light Black are 'exploring links between art and science', curator Janice Lally jumps on the fashionable bandwagon, dispensing with 'craft' altogether in the title and welding art and science in what is a simplistic union. Light Black, an exemplary exhibition by three outstanding practitioners, does not need such pretentious claims.

Craft practice at its best, as exemplified by Light Black, not only retains vitality and relevance, but also gains resonance from its connection with traditional practices. Pejorative perceptions of 'craft' as a term to describe specific areas of art practice, are largely a matter of fashionable misconception, abetted by the institutional apartheid of craft organisations and their increasing preference for 'design' as terminology of choice, however inaccurate. This situation is reinforced by Australia Council policies that marginalise craft (but that's another story).

As for the link with science, rather than illustrating the veracity of scientific knowledge the work in Light Black attests to an essential difference from science in ways of understanding the same biological, organic world. The power of the work lies in its embodiment of the subjective truths of individual perceptions as distinguished from the objective truths of science. It is the superlative craft skills of each artist, their profound knowledge of materials and technical expertise, which provide the means for this poetic embodiment. Scientific knowledge of such fields as human anatomy and marine biology plays a subsidiary, supporting role as a source of reference.

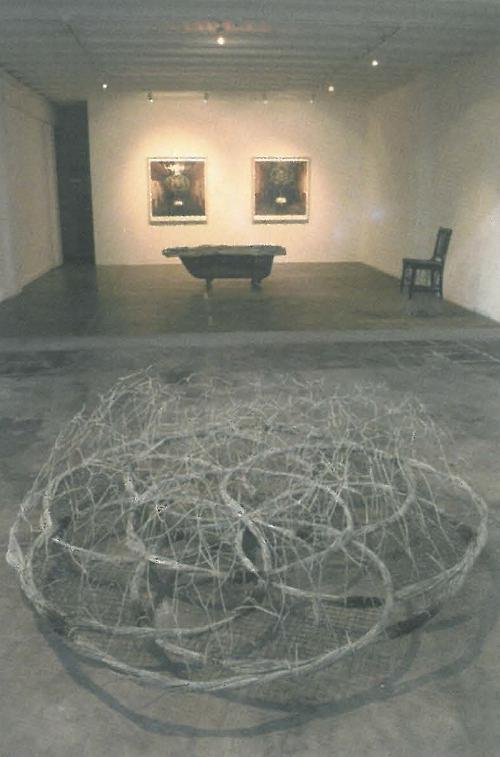

While Light Black gains a superficial visual stylishness from the dominance of black, offset by white and red, there is a deeper and more genuine synergy between the cast ceramic forms of Robin Best, the carved, dyed and burnt lime-wood sculptures of Catherine Truman and the blackened steel sculptural forms of Sue Lorraine. This is a connection that grows out of their shared interest in the distillation of organic and biological form into artistic form.

Robin Best's use of organic decoration owes a debt to the19th century – both to Ruskin's aesthetic philosophies of art inspired by natural form and to German biologist Ernst Haeckel's exquisite illustrations of marine organisms in his landmark book Art Forms in Nature. In her Fleurieu Marine series the surface of each finely cast, semi translucent porcelain vessel is encrusted with intricate textural decoration, evoking in its delicacy the fragile condition of the region's marine ecology.

Her new series of Open Cut vessels, are sleekly contoured forms cast in black porcelain, emanating a darkly powerful physical presence. When viewed from above they reveal their hidden inner geological form, a thin layer of green clay compressed between ochre and black. With these two contrasting but conceptually and technically dazzling bodies of work Best affirms her status as one of Australia's most innovative ceramists.

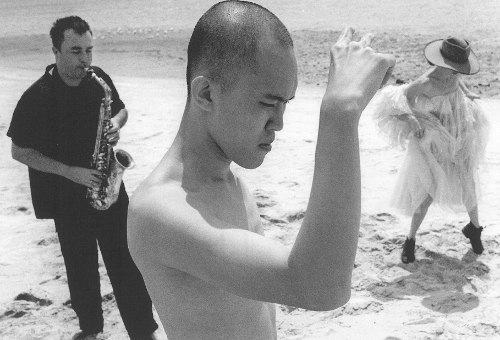

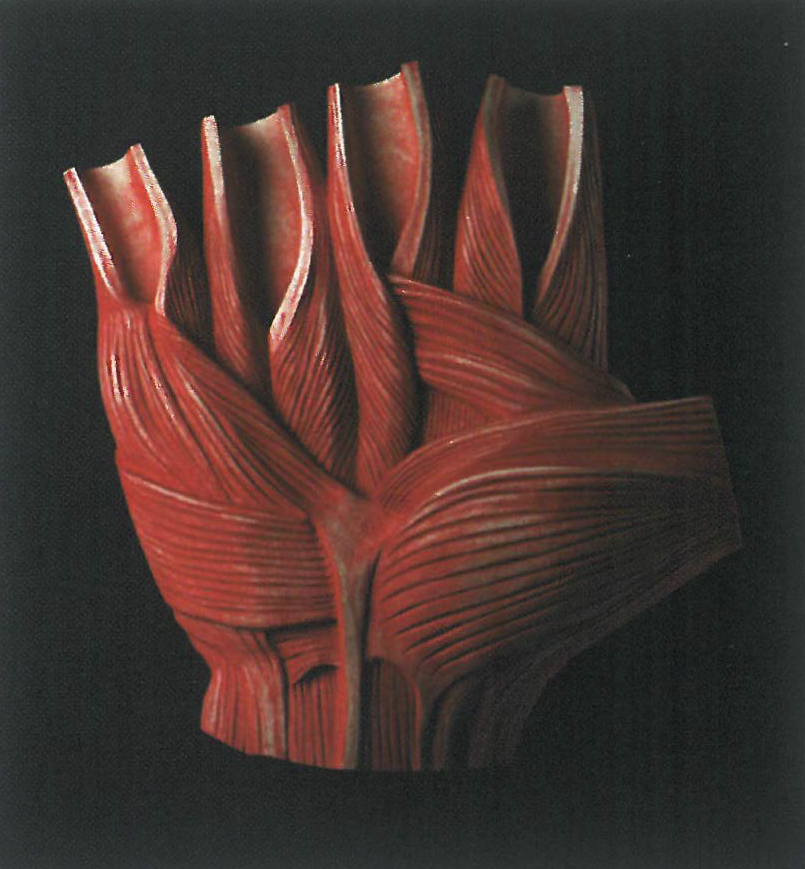

Catherine Truman's new carvings reveal a darker, more anatomically explicit strain to her continuing project of poetically visualising the hidden world of her body beneath the skin. The painfully slow act of carving the resistant lime-wood may be viewed in part as a penance that exacts its price of physical duress on the body, especially the hands. In a miracle of carving, this tension and pain are encapsulated in studies of two hands. Palm Up, dyed with the distinctive Japanese red Shu Niku (or red meat) ink is a fleshy, tightly coiled complex of muscles and sinews. In Palm Down, Truman waxes and abrades the surface to imbue the clenched knuckles with an ethereal translucency and pallor.

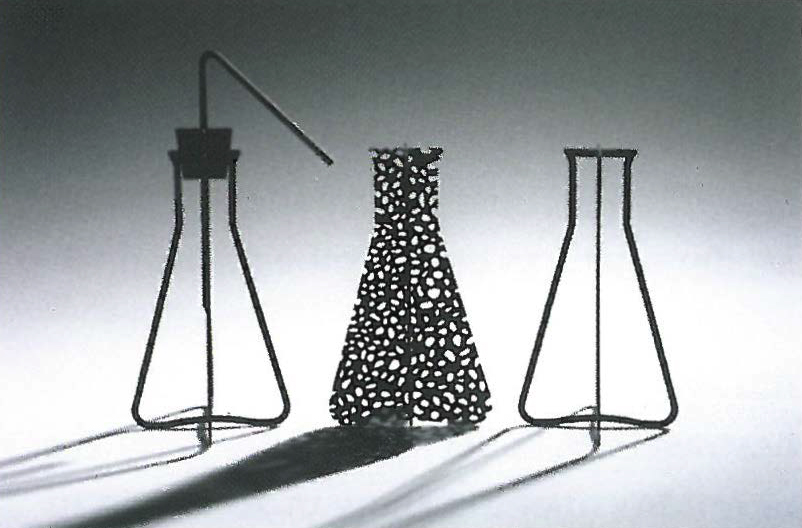

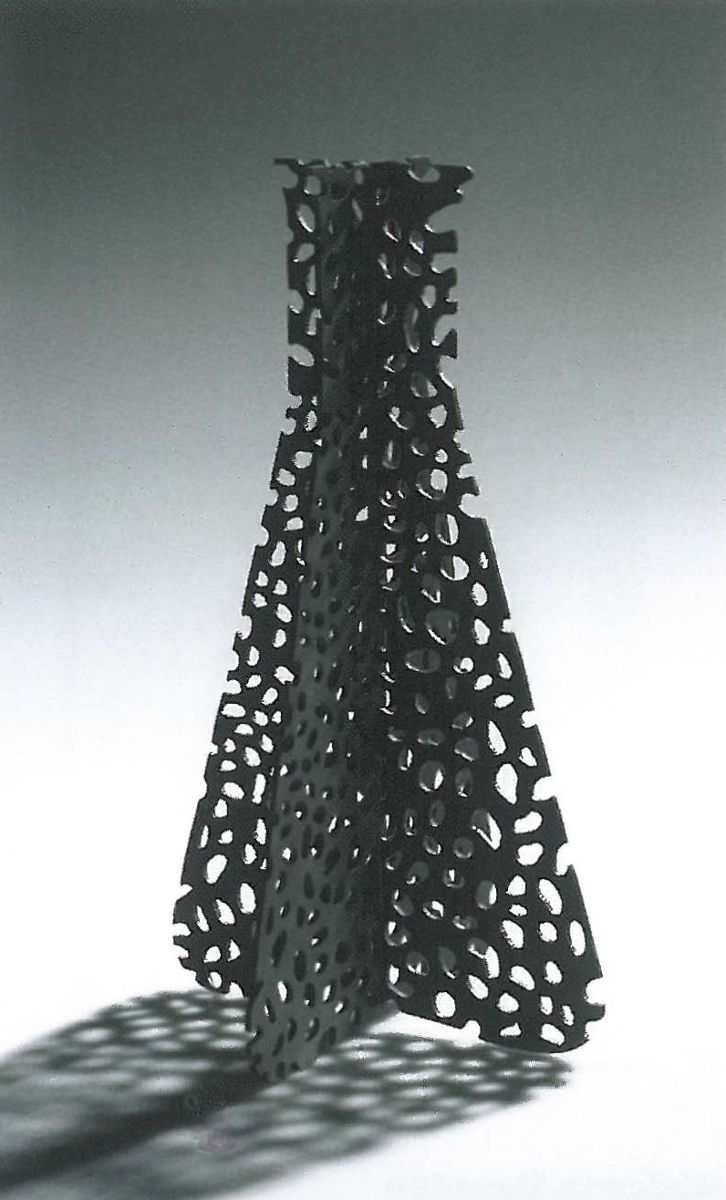

While the work of Best and Truman invites intimate scrutiny to discern subtleties of surface treatment, Sue Lorraine's elegant laser-cut steel silhouettes and linear wall sculptures make their optimum impact from a distance, in a play of darkness and light that belies the material from which they are made. In contrast to Truman's poetic visualizing of the body, Lorraine's approach to the anatomy is coolly semiotic and based on a desire to deconstruct scientific representations of the anatomy. In her curatorial foreword, Lally quotes Lorraine's belief that 'the rapid advances in science and technology are not mirrored in our understanding of the moral and ethical issues these have raised'. Although Lorraine's work is visually satisfying and beautifully crafted, ultimately it cannot carry this weight of conceptual meaning that is attributed to it by the artist.