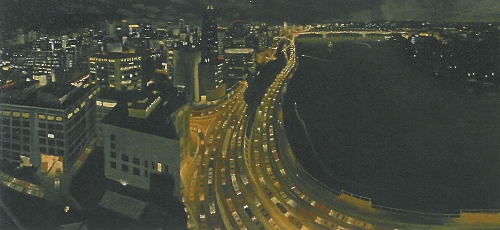

In science critical mass is the point at which a chain reaction begins, usually incited by a smaller explosion. Similar 'cultural' processes can take place in cities, provided conditions are right.

New Brisbane is one of a number of terms - the 200 kilometre city and Brisvegas are others - used to describe an increasingly important port on the Pacific Rim: a city with a troubled history, dating from when the people of mi an jin were displaced by the convicts and jailors of the British empire in 1825. It was a garrison town then, with a fifty mile zone excluding free settlers. It was a garrison town again between 1942 and 1945, when General Douglas Macarthur and his US troops occupied the city. The Brisbane Line, a perhaps mythical Defence Force strategy, was drawn from Brisbane to Adelaide. The country below would be defended; the country above would be scorched and left to the Japanese. Maybe these histories impacted on the city's psychology. How else explain Queensland's attitude to State of Origin?

We live increasingly in city-states, where nationhood is diminished, and where cities compete for their own place in the world and strive to establish their own 'identity'. The term New Brisbane, and the realities of changes to the city have been ascribed to Jim Soorley, the Lord Mayor from 1991 to 2003. His Labor administration played a key role in changing the city's culture. The Brisbane City Council was the first Australian local government authority to fly the Aboriginal flag (it has flown every day since). More recently Soorley demanded that the flag of the United Nations be flown alongside the Aboriginal flag, the city flag and the Australian flag in protest over Australia's involvement in the Iraqi war. These actions - disturbing to many - together with a strong commitment to arts and cultural development, changed prevailing perceptions of the city.

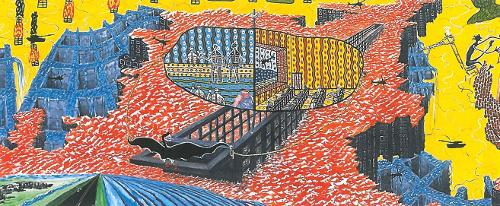

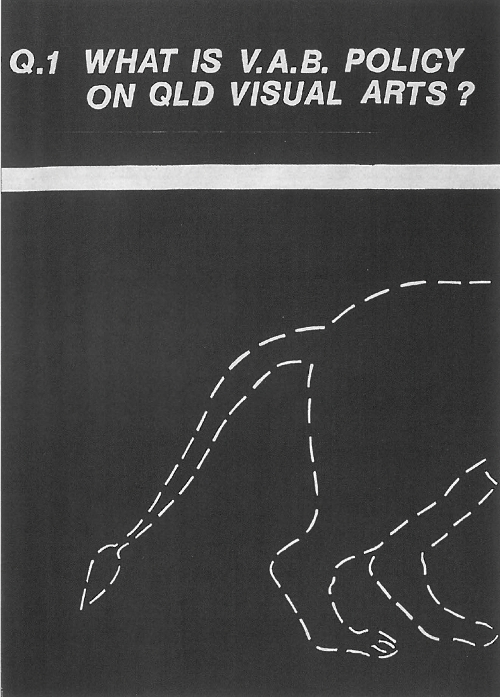

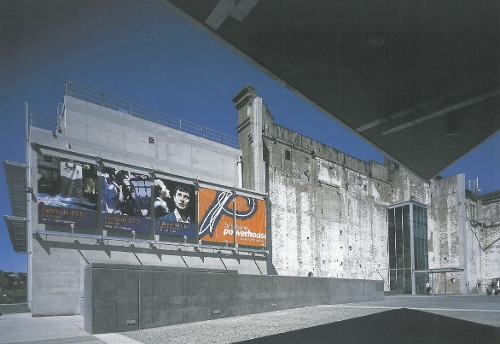

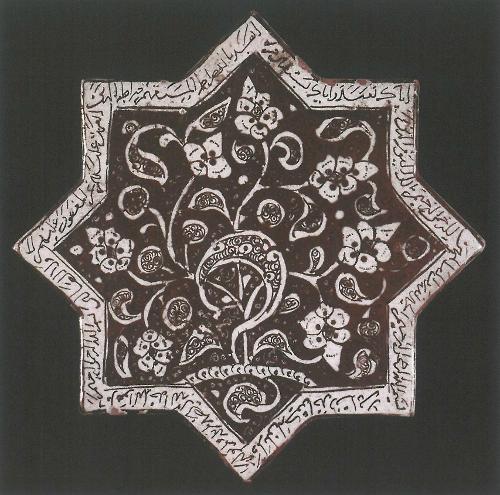

The Brisbane City Council rivals the state government in power and influence. This is particularly apparent in the arts. When the state builds an art gallery, the city opens one too. When the state starts an arts festival, the city matches it. Two highly acclaimed theatre complexes – the state-funded QPAC and the BCC funded Brisbane Powerhouse – compete for critical acclaim. While Queensland is best known for the oppressive climate of the Bjelke-Petersen era, there was a time when it was a progressive state. It elected the world's first Labor government; it was the first to abolish the death penalty, and to introduce free hospital care. In the ten years since Joh there has been a return to openness and progress. Continuing migration to South-East Queensland (particularly from other states), links with other cities of the Pacific Rim, development of the seaport and airport have brought not only trade, but ideas. It's no coincidence that the Asia-Pacific Triennial found its home in Brisbane. The APT's dialogue with the Asia-Pacific region was based on, and then enhanced, existing economic ties. Multimedia Arts Asia Pacific (MAAP) also is in constructive dialogue with Asia around the development of new media.

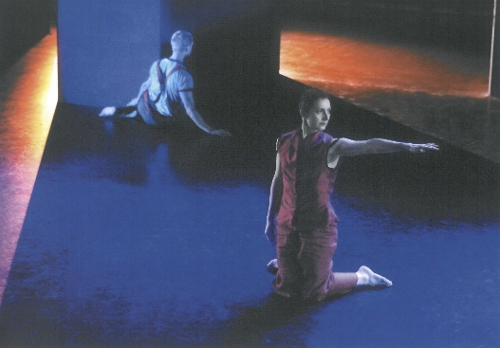

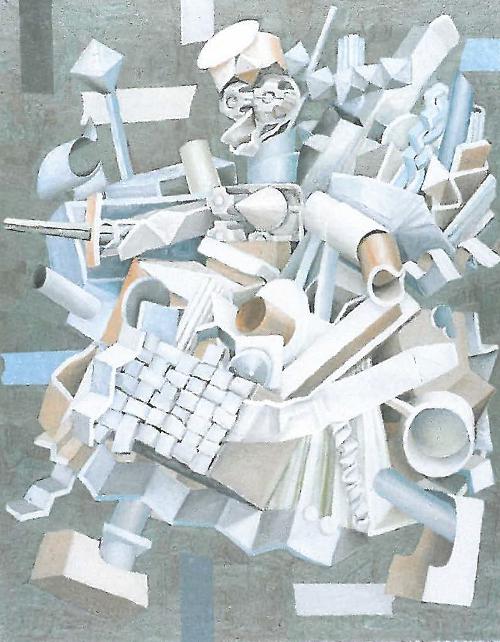

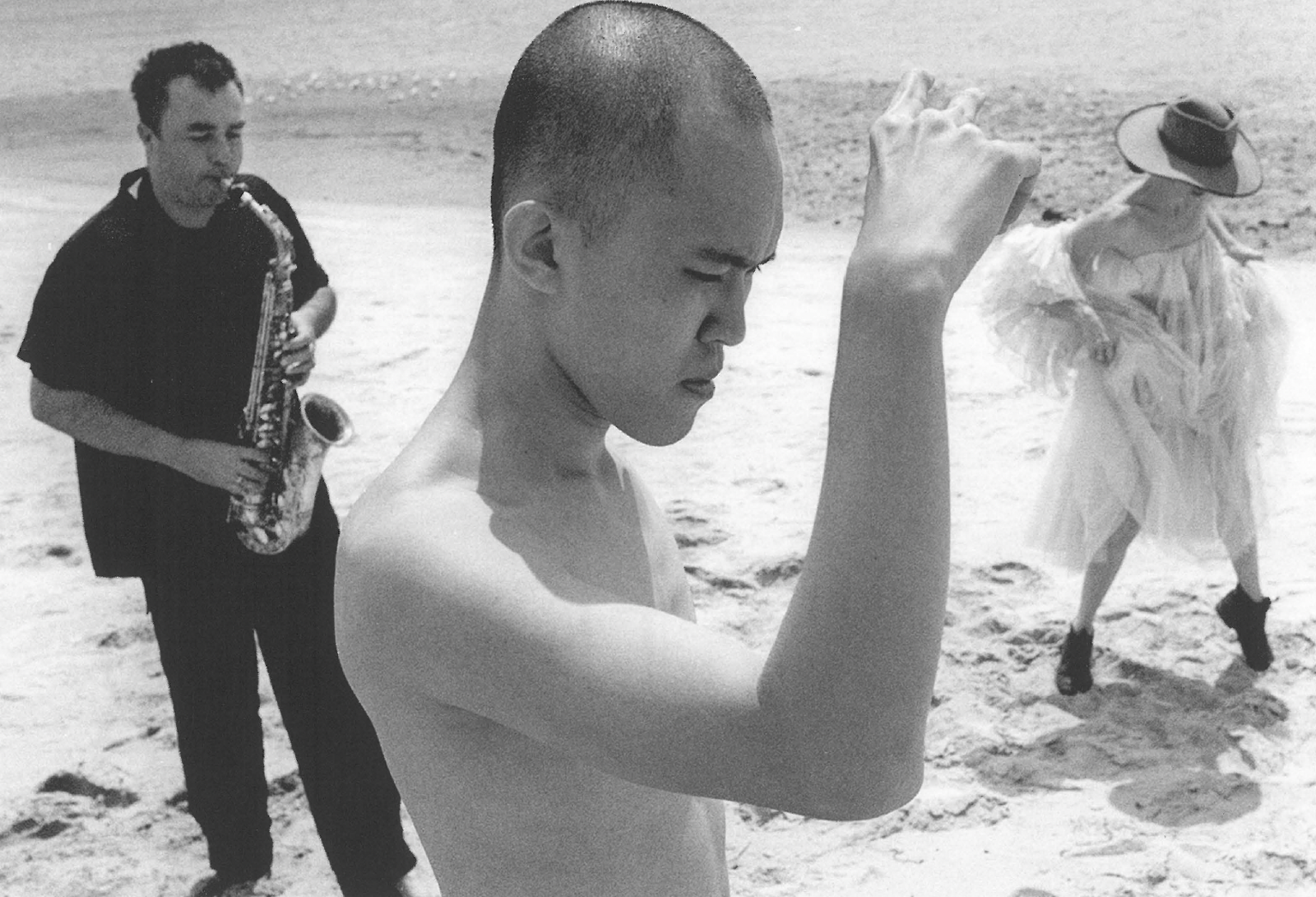

These links are part of a wider transformation of cultural industries within the city. The arts as much as trade have been a means to development of city identity. The success of the Campfire Group in 'exporting' to Europe is evidence of a strong and confident Brisbane Indigenous community. Through organisations like Elision and Rock and Roll Circus, there is a vibrant hybrid arts practice, perhaps more than visual arts typifying the risky edge to Brisbane culture. And film and television production has boomed from less than $10m a year to more than $150 million in the space of a decade.

Where did all this intensive activity come from? The Key Centre for Cultural and Media Policy had a big influence on Brisbane town and cultural planners through the 1980s and 1990s. The Key Centre, in creating policy debate, acted on a desire by city and state leaders to reinvent the city as an important Asia-Pacific port. But policy alone does not bring change. Brisbane also happened to be in the right place at the right time in terms of economic development (it is the most accessible major port on the east coast).

Brisbane is perceived as a sprawling, almost wayward, city, but it has surprisingly compact cultural infrastructure. Most major institutions are located in the precincts of Fortitude Valley/New Farm and Southbank/Gardens Point, bringing vitality to the city centre. This is most apparent standing on the Goodwill Bridge linking South Bank with Gardens Point. Initially criticised as wasteful of taxpayer's money, this 'unnecessary' footbridge was crossed by millions of people in its first year. Students cross back and forth between the two universities, families on rollerblades, tourists and the inevitable Brisbane hobos, provide a sense of cultural critical mass.

But a number of concerns linger. If by 'critical' we mean feedback and analysis – a city that can think hard about itself - perhaps there is still some way to go. For all its vitality and optimism, many writers in this issue express concern about the city's neglect of its past and the bulldozing of buildings that provided both artists' accommodation and a sense of cultural history. This may be the price to be paid for growth, but without an awareness of history there can be no sustainable culture. All will be transitory.

There are, however, positive signs that a 'critical' process has begun. A logical sequence of events has unfolded; first came the questions posed and discussion prompted by the Key Centre for Cultural and Media Policy Studies. The Brisbane City Council took note of its multi-disciplinary approach to cultural/arts planning and implementation while the state also played an important role in policy and infrastructure development. Art Schools have developed innovative courses and arts education for young people is being taken seriously (note the Queensland Art Gallery's Children's program and the Kid's APT). These efforts are refreshing attempts to inculcate an appetite for contemporary art among young people and to involve them in the public life of the city. Finally, there seems to be a community-wide acceptance of experimental art. Perhaps in Brisbane's case criticism, analysis and debate about history and identity will follow rather than precede change.