I was glad we had booked a hire car before we got to Tasmania. A festival which happens in every corner of the island can be certain of one thing -– that the rental car firms will be happy. Ten Days on the Island has many reasons to be pleased with its second edition, which has vindicated the faith of the Premier Jim Bacon, also Minister for the Arts and Chair of the Festival Board, and that of many leaders in the community, that through a biennial arts festival Tasmania could achieve a vast range of positive things, not least of which is improving its image. When most people think of Tasmania they think of cold weather, wilderness, logging, the Franklin River, abandoned mining towns and perhaps double brie, and clear-felled hillsides.

They do not necessarily think of new opera, painting, music, porcelain, furniture by designer-makers or digital art. Ten Days on the Island is an example of inspired thinking on the part of artistic adviser Robyn Archer to make Tasmania the hub for other island dwelling artists elsewhere on the planet, whose particular sensibilities are thus placed in context. Despite the global village and air fares coming down, there is still something different about living and working on an island and the event allows visitors to reflect on this as they follow the festival trails around the state. What they find is a hive of activity in the arts across all media and disciplines way out of proportion to the state population of 500,000.

My ten days were actually only five, and I had to limit myself to looking at visual arts, with one notable exception, and there was an energy and vitality in much of it, despite, or perhaps because of, the very limited funds available.

Con Koukias is one of those resourceful people, who is not only a very talented composer but has worked in Hobart for more than a decade to establish a niche for new opera production of the most innovative nature. His company IHOS performs at festivals on the mainland, but Koukias' dedication to local talent drew him to form the IHOS Music Theatre Laboratory in Hobart.

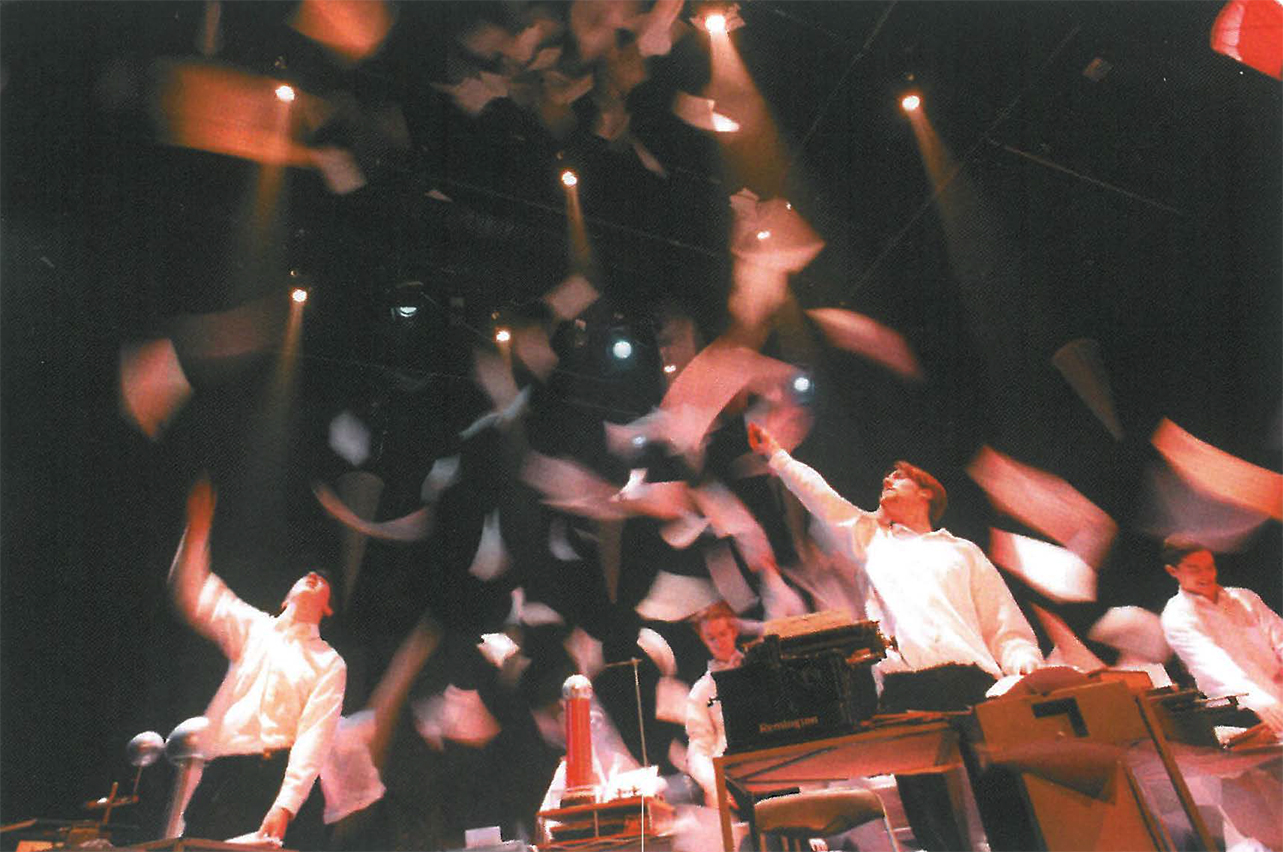

Opening night of the world premiere of his work Tesla: Lightning in His Hand saw an expectant crowd pick their way in the semi-dark to bleachers set up in the Princes Wharf No 1 Shed, in the heart of the port and just adjacent to Salamanca Place. (Hobart is a small city and walking between festival venues yields delightful surprises, like the African and Oceanic art shop nearby whose collection would make most museums green with envy.) Tesla was a Serbo-Croatian inventor born in 1856, an eccentric engineering genius who harnessed electricity into alternating current, emigrated to the US and had a lengthy, disturbed career working alongside Edison and Westinghouse. His later talk of space exploration and death rays caused the FBI to investigate him as a security risk. The 'capturing' of lightning in a Tesla Coil seems, through Koukias' interpretation of his life, to epitomise the personality of this man; complex and arresting lighting effects are used throughout to build up the confusion and conflict which followed his inventions, their patents and commercialisation. At every turning point in the story the principal singers are embedded in a 50-strong male choir who are employed as a grid of ciphers with strongly sculptural props acting out various roles, typists, factory workers, demented filing clerks hurling paper in the air. There are thousands of light bulbs, pigeons, sand pouring through swinging cones, overhead projections, rows of refrigerators, striped light and a real Tesla Coil in a Faraday Cage, in addition to a children's choir and a live orchestra including classical and electronic instruments and a theremin.

This work has been several years in gestation, with three 'work in progress' performances preceding this. IHOS, like much music-theatre and hybrid practice in Australia, lives from hand to mouth and must operate accordingly. The male choir are amateurs from around town, the technology is mostly on loan and it is hugely to Koukias' professionalism that everything went without a hitch. The evidence of this final version of Tesla shows that it has the makings of a great opera in terms of wonderful music and visual design. A smart librettist who could crank up some tension in the dramatic content would surely tip it into a world class event.

Arriving in ghostly Queenstown, a landscape blighted by sulphur fumes from the mine now closed, we discovered in the old Mines Office Hard Rain an exhibition of painting and objects curated by Sean Kelly and Mining the Imagination, a CD-Rom based interactive interpretation of Queenstown made by a team headed by Richard Bladel. What hit me on leaving was the impossibility of really understanding art of a place without being there. On the five hour drive from Hobart the mythical, 'Hydro' had suddenly materialised around various bends in the road, parallel rows of massive black pipes plummeting down a hill from some unseen high place. The old battles of power generation versus wilderness are now replaced by logging and the rather small almost picturesque power stations one comes across in these green valleys seem to belie their fearsome reputation during the Battle for the Franklin. These landscape icons, shapes and locations appeared obliquely in most of the works on show; without the seeing could I have recognised them?

Of the many other shows on during Ten Days, the three powerful rock and water paintings by Philip Wolfhagen hung in the new Queen Victoria Museum and Gallery building in Launceston stood out. These are great works shown to perfection in the imposing but friendly spaces created out of the old railway yard buildings at Inveresk by architect Andrew Andersons, inspired remodeller of so many of our best art museum spaces.

Perhaps the event most nicely tailored to the travelling festival-goer was Jane Deeth's invitation to artists to make installations at five points on the Midlands Highway between Launceston and Hobart. Hwy 1 stopped motorists from getting from A to B in the quickest possible time by inviting them to stop at the old staging posts and take time to contemplate the history and current situation of these places now that they have all been bypassed by the highway. Two of these made a lasting impression. At Cleveland House, an old inn, an unattended installation by Bron Fionnachd-Féin awaited the unsuspecting visitor in its 19th Century stone stables. Already thrown off-balance by ancient cobblestones and the gloomy interior, the row of horses' tails pinned to the walls complete with roughly cut rump hide indicated that we were confronting animal death; judging by the smell it was not long in the past. From a passage-way where the courses of the whitewashed stone walls were lined with horse hair, was a row of small rooms each containing a full size cast-iron bath on legs. The baths contained a yellowish liquid, and each was tethered to a ring set in the wall. Beyond this another room, this time containing three tables each set for a film noir meal consisting of the words 'fold', 'enfold' and 'unfold' carved out of fresh hide. It was in the final room with three horse carcasses, old-fashioned cotton frocks on hangars and an afternoon tea setting with dainty cups containing more of the yellow liquid that the smell became nauseating and one rushed for the door, thankful for the innocence of the little lawn, blue skies and trees beyond. Those knowing visitors who think about the urine of pregnant mares and its role in hormone replacement therapy would have understood the title one season: 'just like her' and pondered the fate of horses in today's 'civilised' society. Courageous in confronting these things and skilful in achieving such quiet menace in her piece the artist faces us with one of those ethical questions which will not go away just because these days it is never mentioned.

Further down the highway at Campbell Town, the healthy fecundity of vegetables and flowers growing in vigorous profusion in three large circular beds set up its own associations. Bok choi, spring onions, parsley and silverbeet set amongst marigolds, nasturtiums and white flowers (?) were planted so as to form three Chinese characters, which together mean 'Australian'. Greg Kwok Keung Leong chose the site of an early Chinese market garden to grow his symbol of a multicultural society, carefully fencing the area off and constructing a little wooden viewing platform outside the fence in the manner of annual Flower Day ritual viewing and judging. Set on the margins of the town on the far side of a creek it felt slightly isolated, as the Chinese would have been then, and as they continue to be in some circles in today's political climate. It seems apt that the process of making this 'exhibit' a considerable distance from the artist's home in Launceston combined with the lack of resources turned it into a community project, with scores of local people, including traders, cheerfully mucking in at every stage to help a Chinese-Australian artist make a good-natured statement about their forbears.

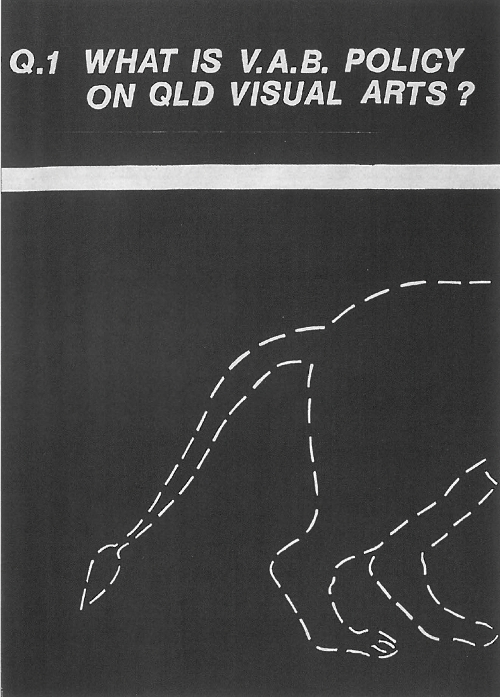

Thankfully the visual arts at Ten Days were not impacted to the extent of some sectors by the widely publicised boycotts by prominent artists and writers regarding Festival sponsorship from Forestry Tasmania. Boycotting artists and writers joined forces to organise Future Perfect, a parallel event in North Hobart in shop windows, pubs and galleries ironically adding greatly to the festival ambience and involving more people at a grass roots level than most sponsored events could hope to do. While the environmental issue is absolutely real and artists of principle are right to stand up and be counted, the wounds and schisms in this small arts community caused by what seem in part to have been badly targeted protests (apparently the Readers & Writers Festival which was the worst affected event did not even have Forestry sponsorship) combined with peremptory responses from the Festival need to be healed if Ten Days is to gain strength and achieve national and international recognition. Given the potential of the arts to affect political decisions it would be a tragedy if this attempt to use the Festival as a vehicle by which stop the logging were to close off one of the very avenues by which Tasmanian artists can become more influential in the community.

chain, installation at Cleveland House stables as part of HWY1.