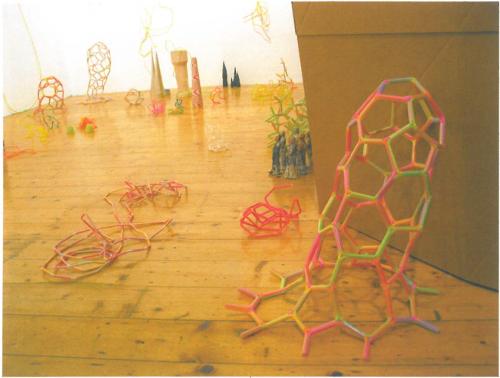

Encountered in a gallery only just tall enough to contain it, Brad Nunn's sculpture Machine Gun Walker, is a daunting object. It's big, it embodies the mutant biker technology of the Mad Max films, and it raises the question of who would use such a thing. The work gives a new and disconcerting connotation to the term 'power walking'.

It is, in theory, a prosthetic device for the disabled, a custom-modified walking frame the likes of which are regularly used (minus the weaponry) by thousands of people who rely on assistance from technology to go about their day's business. The extent to which conventionally-abled people rely on special devices to do things they otherwise couldn't (such as travel long distances in a short time or instantly expand their available memory) has led to the proposition that the human body is now technologically obsolete. Nunn acknowledges Stelarc's vision of a world where to be human is to be augmented and enhanced by technology. The mind is programmed to a higher level of performance than the body, which can't do all the things people need to do. The disabled have understood this proposition for much longer than everyone else.

Nunn's works are produced through computer-aided drafting and laser cutting. This is a fairly standard practice among sculptors and particularly designers, but the technology is especially valuable to Nunn, who was affected by a stroke in 1993 while a student at the Queensland College of Art. His working method, the assembly of fabricated components, is adapted from boyhood hobbycraft model-building.

A penchant for finely engineered and meticulously structured implements has been further developed by an interest in medical equipment. He has taken prosthetic devices as subject matter several times in the past, generally enlarging them to an extent that emphasizes their strangeness. The objects he has represented (such as specially modified tableware and footwear) are known and immediately recognizable objects that have been altered, sometimes only slightly, to suit the needs of people for whom the standard model is less useful. Distortion to the form and scale of familiar things, making them extremely unfamiliar, is essential to the impact of these works on the viewer. Sardonic humour also recurs in this area of his work.

As installed at the Institute of Modern Art, the big Machine Gun Walker sculpture faced a wall of tiny cutouts of various generic designs for walking frames. Apart from being positioned to blow these conventional models away, the super-modified walker seemed even more monstrously big when seen in their company. The viewer was more conscious of being dwarfed by the huge apparatus when made to feel like a giant by the minuscule objects on the wall. Human size was made immaterial by these discrepancies of scale, and the physical body made irrelevant.

Machine Gun Walker is startling because it combines two devices that seem not just unrelated, but emblematic of radically opposed aspects of human experience. The walker is a byword for old age and infirmity. The machine gun represents aggressive power. This diametric opposition is integral to the meaning of the work, but so is a rather poignant connection between the two components. The Vickers machine gun reproduced in this work was the one used in World War I, World War II and the Korean War: the wars in which those who fought are now of an age when walking frames would have taken the place of guns.

As a white middle-class male, Nunn is a member of the patriarchy that is most stridently expressed in military might, yet as someone with what he describes as a 'dysfunctional body', he can identify with the patriarchy's other. A childhood spent tinkering in his father's workshop, plus a youthful interest in the structural armature of early 20th-century aircraft and a fondness for the Biggles novels about a British fighter pilot are elements of social conditioning for a particular role that is now embodied and contradicted by his work. The structural engineering of an object such as Machine Gun Walker, which has about 600 individual components, reflects a mechanical aptitude that has not been blocked by impaired motor skills and has been applied to art rather than military hardware.

The machine gun is an extreme statement of the kind of power to which the disabled are denied access, and the walking frame is the kind of equipment with which they are more commonly associated. Nunn describes what he is doing as looking at prostheses from an impaired person's point of view. The machine gun is the fantasy, the walker is the reality.