The exhibition demonstrates that contemporary art does not come from a void but emerges from the complex trajectories of geographical exploration, trade and colonisation.

This sentence is the wall text which prefaces Fabrics of Change at the Flinders University Art Museum though I could not find it in the accompanying catalogue. Does anyone really think that contemporary art comes from a void and is not imbricated in history like all art? The tone of this text, didactic and patronising, pervades this exhibition which is overall much more like an illustrated thesis than a visual art exhibition. That said there is some rich material here which reverberates with significant resonances even though it is somehow muffled by its presentation.

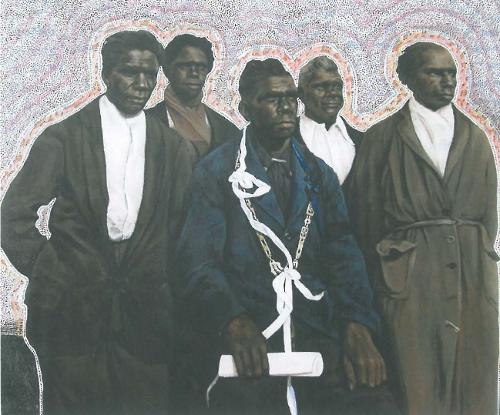

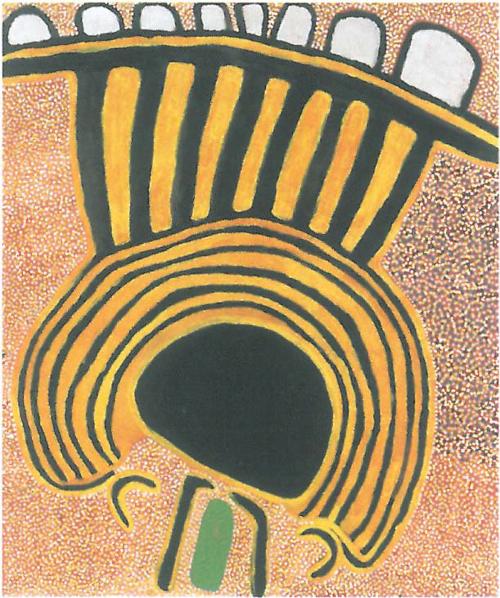

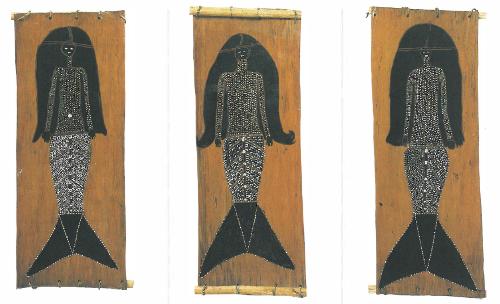

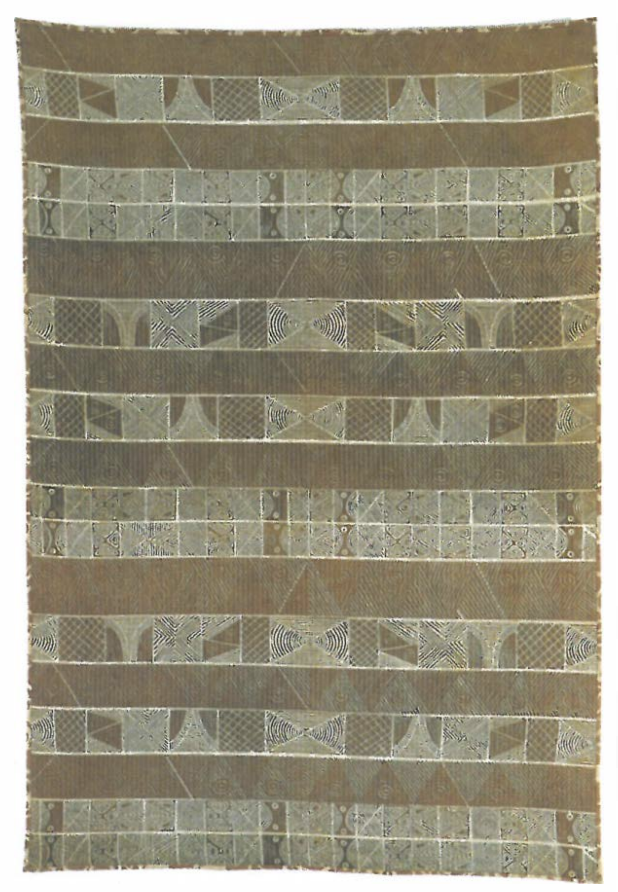

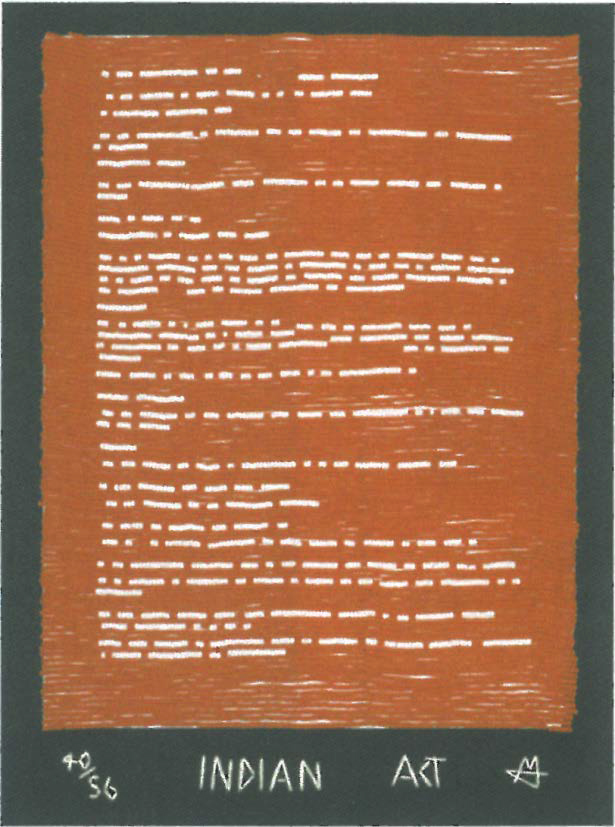

The exhibition's thesis - that colonised cultures used and use elements of colonising cultures, sometimes critically, sometimes with great joy, to continue and develop their own material cultures is hardly new but it is a postcolonial one currently very fascinating to many people. The thesis is demonstrated by Indigenous artists: John Pule with a lithograph combining Niue and pan-Pacific imagery; Bathurst Islander Osmond Kantilla's silk-screened blanket of traditional designs; Mary Mungatopi's etchings of objects from the Mountford Tiwi heritage collection (many of the relevant objects were borrowed from the South Australian Museum to be shown alongside the prints); and Canadian Nadia Myre's more overtly political work, a communal project initiated by Myre and Rhonda Meier in which fifty-six pages of the Indian Act were embroidered with beads in an act of resistance and restitution.

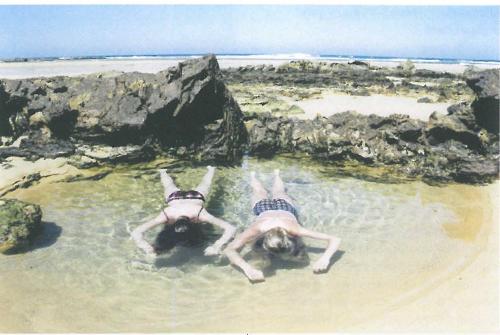

The survival and development, the transition and transformation of cultures are implicated in Jubelin's cool precise work which uses the wordless language of the stitch and the multi-stranded stories of fabrics and their journeys around the world. One of Jubelin's works shows a rendition in petit point of an Irish linen cloth hemmed by Tiwi women in 1974. In the catalogue it is flanked by a photo of Tiwi women hemming just such cloths taken by Fabrics of Change co-curator Diana Wood Conroy who worked at Tiwi Designs on Bathurst Island in 1974.

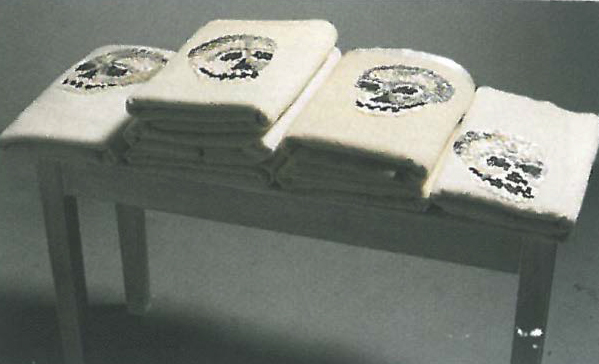

Kay Lawrence's Folded, All I have is a voice to undo the folded lie consists of grey and white pearl buttons sewn into skull forms on cream blankets folded in piles on a table. The blanket is a recurring colonial artefact. Like glass beads, flour, tea and tobacco, blankets were given to Indigenous people and sadly sometimes those blankets were infected, whether deliberately or not, with disease. Lawrence's skull, a memento mori, originated in an Italian medieval mosaic, pearl buttons connect with the global pleasure taken in their iridescence and the historical journeying of pearl buttons around the globe. The work reminds us that Aboriginal divers in the 1860s provided vast quantities of shell to the textile industry in Manchester.

It was disappointing that the exhibition's prize syncretic object of a Victorian leg-of-mutton dress made around 1880 in Samoa from traditional block-printed tapa cloth, which belongs to the Macleay Museum in Sydney, could not travel. It would have been good if at least it was represented by a substantial photograph.

It is interesting to contemplate whether there are differences between Jubelin and Lawrence's work and the other pieces. If a colonising culture uses something from a colonised culture it is called appropriation, the other way round it is a testament to the vitality of tradition. But perhaps our ideas about cross-cultural interchanges are now more flexible.

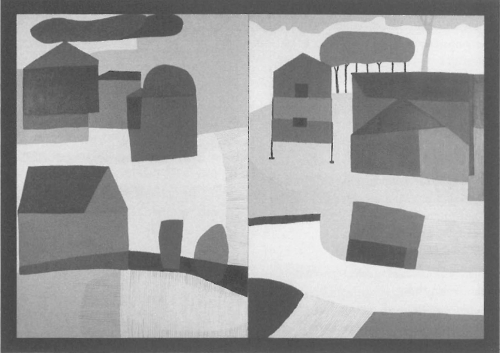

Slightly on a tangent is a display of samplers from the making of Kay Lawrence's splendid design for the impressive and moving Parliament House Embroidery (1984 - 1988) in Canberra. Here one person designed and many anonymous people embroidered. The work does not quite fit Fabrics of Change's rubric of cross-cultural investigation or the revival and persistence of tradition. Yet it is possible to discern the anonymous embroiderers asserting their opinions and personalities in interpreting Lawrence's design, thus the multiplication of history into many stories that the exhibition asserts is amply demonstrated.