It is almost 30 years since Ken Searle first exhibited whimsical paintings based on the landscape of the Adelaide hills. In those years of Ocker Funk, the land was inhabited by kangarigars, mythical creatures that were half budgerigar and half kangaroo. The glory of these works was in part how he sustained his mythological creation right through the entire life cycle of his mythical beast. The other key characteristic of his early works was their painterly nature. In the midst of Ocker Funk, as painting was emerging from the tight control of masking tape and spray gun, here was an artist who reaffirmed the value of the older tradition of the Australian landscape. Right from the start his work was characterised by a sense of place, by the notion that art should spring somehow from the land that nurtured it. Yet these works, and his subsequent paintings of Newtown, the journey from the centre to the west of Sydney, and the Cook's river, all managed to convey a sense of wonder, to make the landscape appear somehow magical and special.

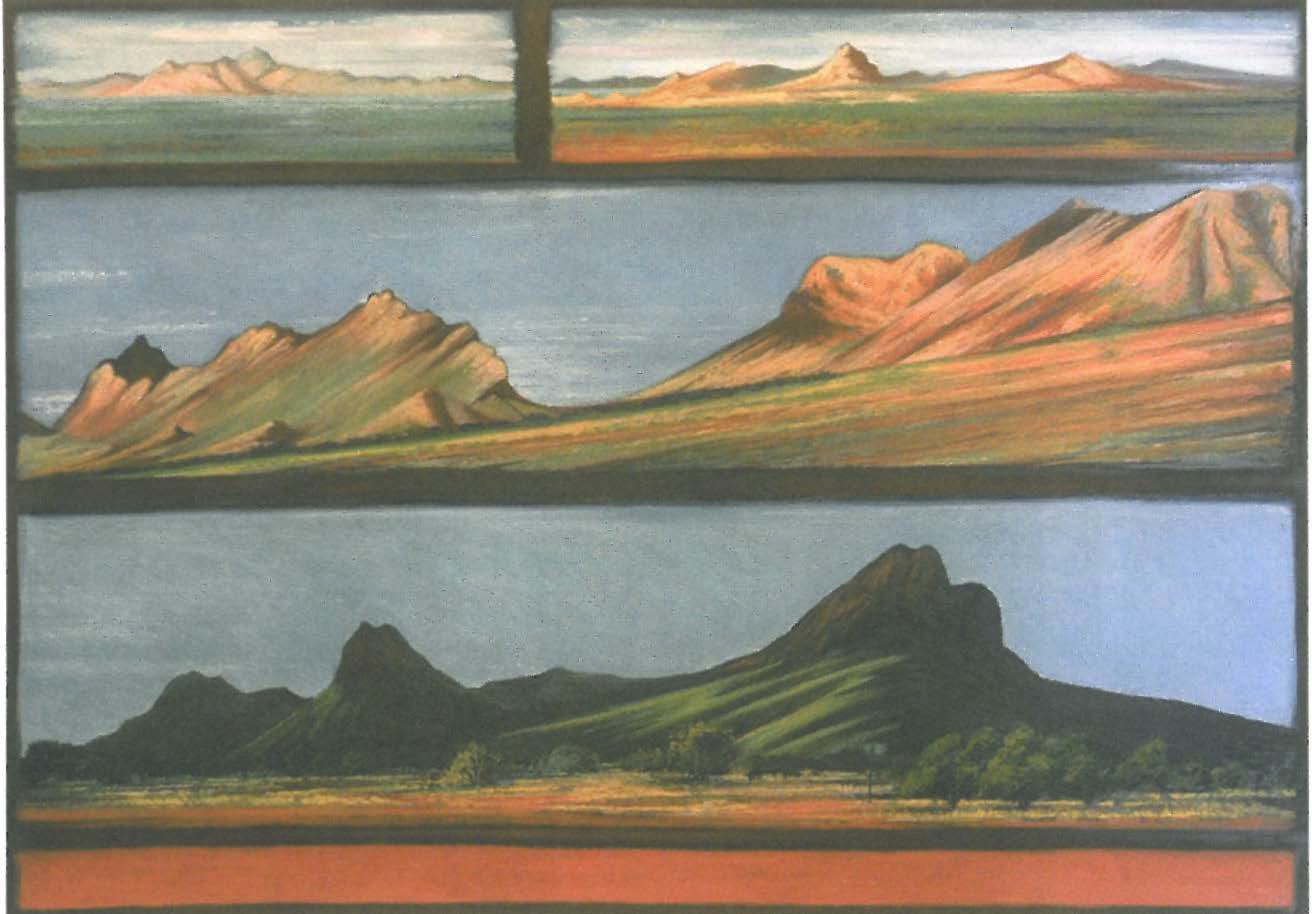

This same sense of wonder and understanding is present in his latest series of works painted at Papunya in central Australia. Searle visited the township for a number of years, working with the people, absorbing the lessons of the land, and now has produced a series of paintings and drawings that reflect his mature vision, works made in sympathy with the land, its people and the traditions of Australian landscape. Some works are panoramas, long thin extended landscapes of desert and mountains, quoting the exaggerated format of some of Arthur Streeton's Sydney Harbour paintings from the 1890s. But Streeton never painted the land so red, the purple hills, the salt lakes. There was one German Australian artist who travelled north from Hahndorf, whose paintings and drawings of the bare hills of the Flinders ranges later impacted on Rex Batterbee and through him the young Albert Namatjira. Sadly many later artists came to believe that these were cliché paintings, and thus ignored their fundamental structural beauty.

Searle draws on the visual lessons of Hans Heysen and Namatjira when he comes to interpret the stark landscape, but he has also drawn on his connections with the land itself, and the people with whom he was working.

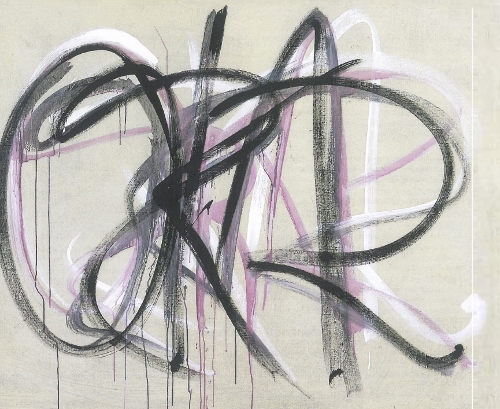

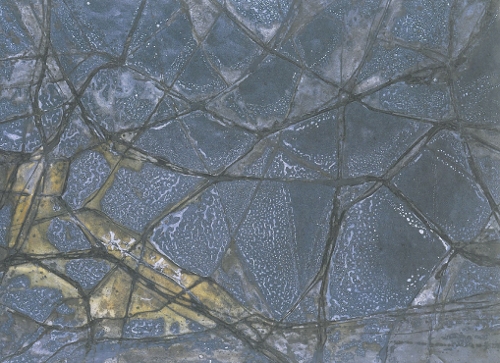

In a remarkable series of works the artist dissects different elements of the land, the form and the colours. He has painted and drawn the hills in monochrome so that the viewer sees them as bedrock, the foundation of all things, the source of all endurance defined by line in light and shadow, but the name of the hills is Sleeping woman, and the folds of the hills echo the folds of a body covered in cloth. In Shifting Horizon, a series of small paintings, he paints the colours of the horizon and the sky framed by brown, which might be a window, to create some of the most satisfying apparently abstract studies I've seen in a long time.

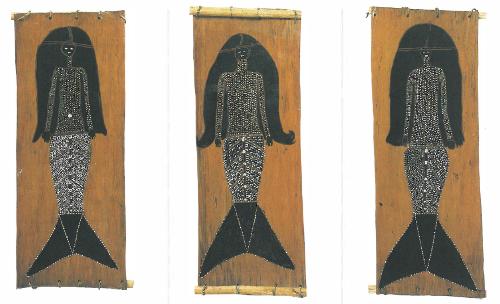

But it would not be Searle without the whimsy, so in the midst of these almost perfect abstracts he places an exquisitely precise Teddy Bear's Arsehole, the name of some local vegetation. Other paintings show solitary boots, abandoned in the scrub, and an upturned car and abandoned wheelchair give a less heroic landscape.

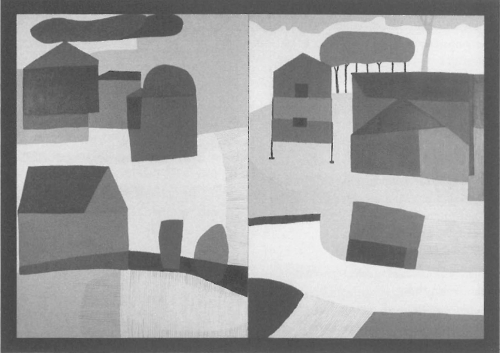

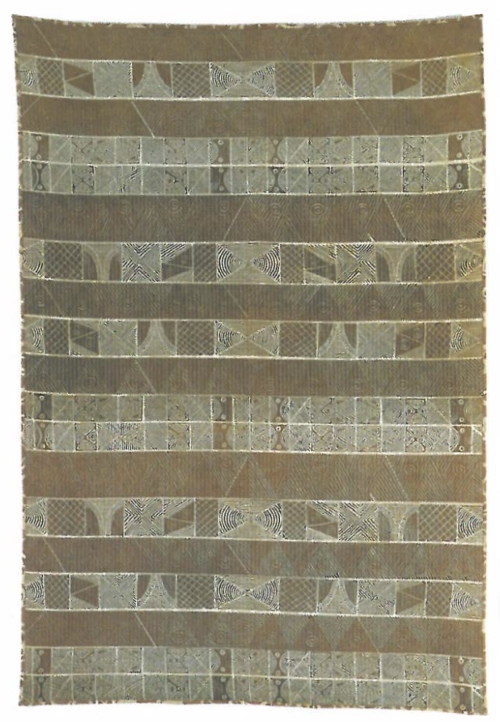

Searle has indicated that he sees this series as a continuation of his paintings of urban landscapes, but there are no works here that use the collaged imagery of his Newtown or West series. Instead there is a series of vignettes that do relate closely to the studies for the older works. These are unusual in that they concentrate on the galvanised sheet metal and brick buildings of the township, a landscape that is usually ignored by town visitors. In one work, Papunya: Bird's Eye View, Searle paints both the houses and the scope of the township, but also the tracks and the roads that surround the town. The overall effect is that the painting looks almost as though Searle is indirectly quoting the work of the Indigenous artists with whom he was working. Yet he has carefully avoided using mythology that would not belong to him. There is no coy appropriation of others' imagery and symbols. The works stand alone as small insights into another place.