It's a cordon, it's a wall, it's a barricade, it's a work by Horst Kiechle that dominates and unifies this year's Octopus at Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces.

In these times when curatorial premises are de rigeur and curators are becoming the new artists, guest curator Nicholas Chambers has set out not to theme his edition of Octopus. Rather he brings together four artists with divergent practices and lets them play; it is refreshing to see established and emerging artists together in one show. It appears that his intention was to link the works by creating a space in which they could be framed. He has chosen artists from a range of cultural backgrounds, but does not ask them to assert themselves as their cultural stereotype but simply as artists.

Horst Kiechle is known for his interest in extending our perceptual boundaries of built environments through the amorphous cardboard constructions that he inserts within modernist architectural and other structures. He asserts that we have the ability to create new, organic spaces to inhabit and the idea of the box as the perfect spatial form is redundant. With Octopus 5 he was challenged for the first time to reinterpret the 'white cube' and also to collaborate with the other artists in this show to create a distinct space for each artist's work.

Made of raw cardboard, bent and curved, shaped floor to ceiling into monolithic walls that recall the Berlin Wall and more recently the controversial West Bank barrier being built by Israel, Kiechle's wall creates three distinct new spaces, it overpowers the gallery space, deadens the sounds and smells like wet pulp.

To my eye the collaboration was in part successful; it worked for the Grant Stevens video works and set up an incidental dialogue with Raafat Ishak's paintings, but overwhelmed the delicate lyricism of Koji Ryui's sculptures.

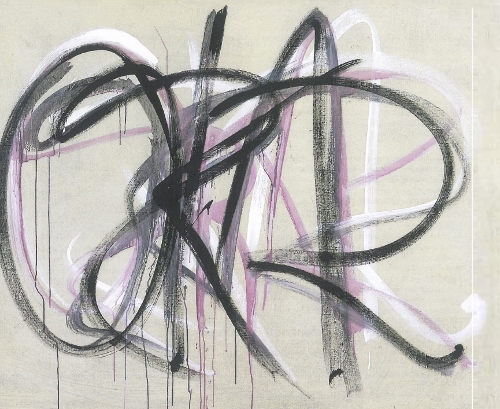

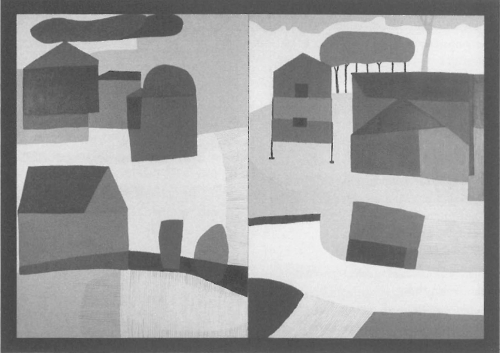

In the front gallery Raafat Ishak exhibits four medium-scale geometric paintings on unprimed MDF. Swathes of raw surface are visible in the gaps of the paint. The paintings are screwed onto the similarly raw cardboard surface, almost melding with it, the geometry speaking more of Mondrian than of Islamic carpets and suggesting that he has diffused the more culturally idiosyncratic imagery of his previous works by choosing a more generic modernist geometry. Could this be a symptom of our times? Has he chosen to make work that specifically gives up culture and blends with or disappears into the surface of the walls?

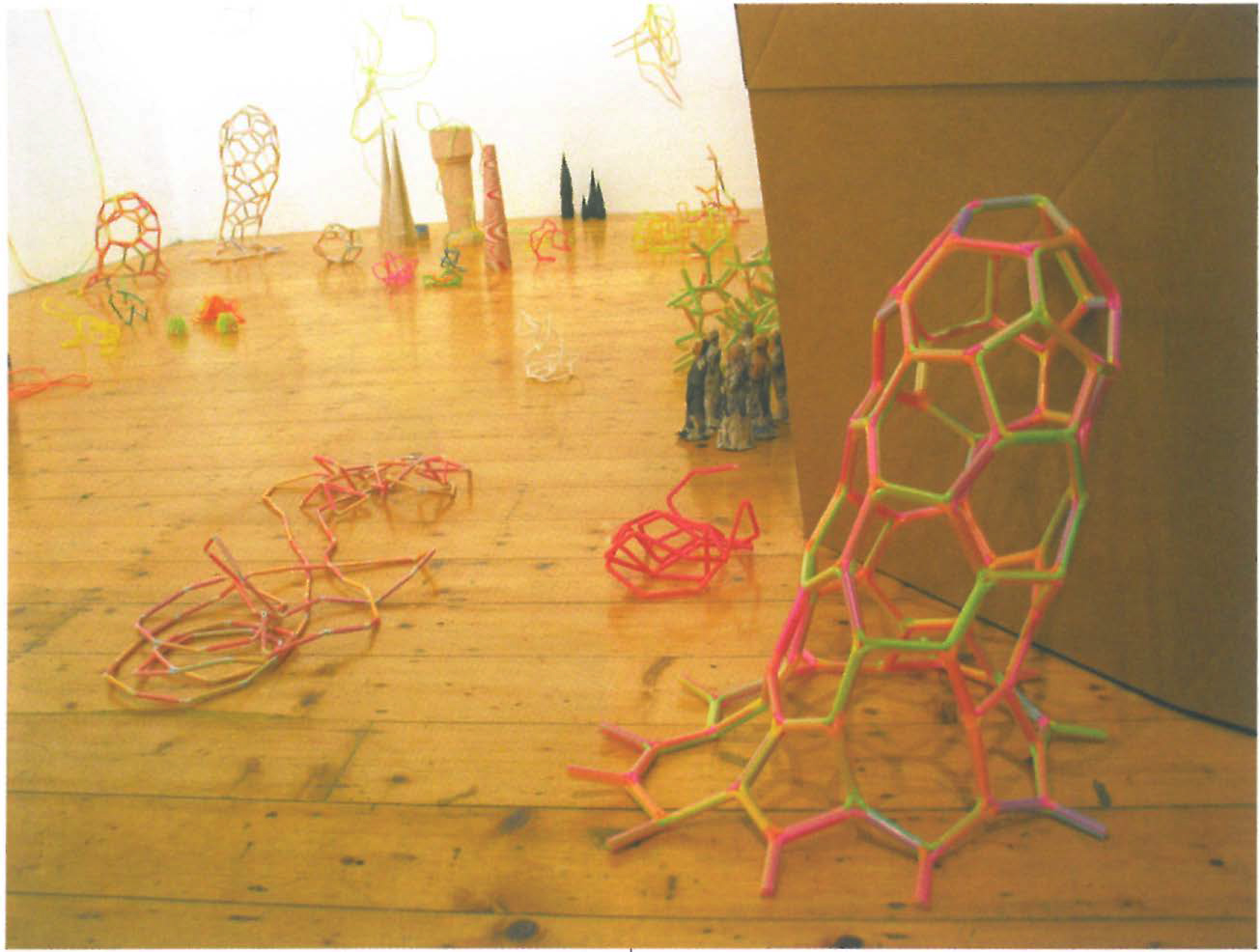

In the open space in the back with its Baltic pine floor Koji Ryui exhibits very delicate works made of everyday materials – drinking straws, streamers, tape, newspaper. He pulls the coloured tapes into towering pinnacles that lean delicately into the space. He joins drinking straws in fantastic molecular-like constructions to highlight their patterning and versatility as a building block, playing spatially with colour and form. Entering the space one becomes a giant in a new Lilliput. Apart from the lithe towering rolls of paper, the majority of the drinking straw structures are less than knee height. I wanted to get down and crawl through the work to engage with its playfulness, but gallery etiquette doesn't inspire this sort of behaviour. Ryui's delicate, lyrical work is subsumed by the brown wall alongside, making it, for me, the least successful of the collaborations.

The cardboard cavern made for Grant Stevens' video work creates an intimate environment for the viewer. This space is perhaps the most successful because it falls into the tradition of cinema, creating a space where we can truly suspend our disbelief for a while. On three big flat screens, made of cardboard painted white, Stevens projects words, and more words, in a fast, syncopated rhythm. They flash black and white on the screen following a monologue by a small voice, word for word. They talk about the existence of God. Oh, it's Woody Allen. A brief moment trapped inside Woody Allen's head. A bit too long in the space and the flash of the words made me nauseous.