A short history of Yolngu activist art

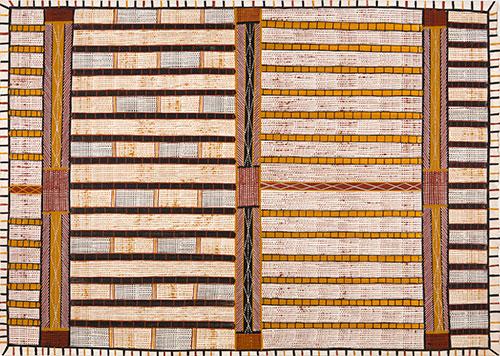

This is an account of some objects that appeared in the 2015 Istanbul Biennial and how two people responded to them very differently. Carolyn Christov Bakagiev was the curator of that Biennial and the person who identified and assembled the objects for exhibition. She proposed in her accompanying text that the land and sea rights achieved through art from Yirrkala formed perhaps the first case of activist art. And, as reported by The Australian, in her opening speech at the media launch “Christov Bakargiev mentioned the bark petition and Saltwater Collection – the theme of the biennial is saltwater – as early examples of art used to further claims to land.” As she stated, “The bark petition triggered the whole process of restitution of lands and it started with this gift of an artwork.”