Juliana Engberg’s Biennale of Sydney is a reminder that exhibitions are events framed by time. Her original vision, as outlined at a media conference at the Sydney Opera House last year, seemed an optimistic exploration of a world in flux. By the time of the official opening, the concept had been battered by a local campaign against the Biennale’s mainstay sponsor, the private company Transfield Holdings, for the involvement by the public company, Transfield Services, in the Australian government’s incarceration of asylum seekers. While most of the protesting artists eventually returned to the Biennale, some did not. Bearing in mind that Libia Castro and Ólafur Ólafsson’s work dealt directly with the world-wide issue of the plight of refugees, their absence was unfortunate.

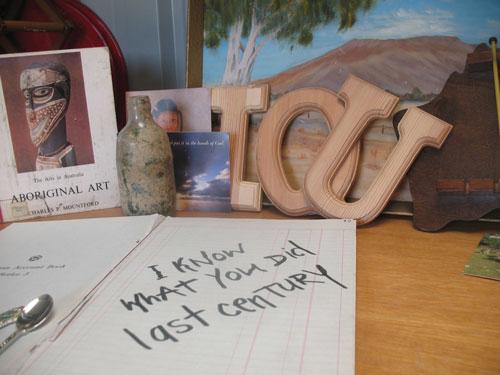

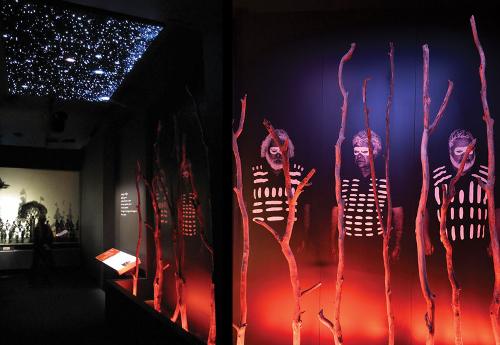

Inevitably the exhibition has come to be seen through the lens of a more politically aware audience, and it has not benefited from the change of context. The other problem with timing is that the Biennale coincided with Adelaide’s Dark Heart. While it is not really fair to compare the smaller Australian-made Adelaide exhibition with the large international Biennale of Sydney, usually that kind of comparison would see the international exhibition reign supreme. But Dark Heart has captured the Zeitgeist, while the Biennale of Sydney has largely missed the bus.

In a world made urgent by the plight of refugees, the looming ecological disaster, the cruelty of bureaucracy and the sheer madness of modern life an exhibition trumpeting “the transfer of creative energy between the artist and their audience” just seems out of touch. Yet some of the art is better than the gloss that surrounds it. On Cockatoo Island, Tori Wrånes’ compelling performance piece The Stone and the Singer, mingles ancient music, the performer as a singing mythical figure and a stone pendulum – swinging just above human height. There is a certain controlled lunacy here as though Wrånes’ work has a primitive energy that puts it as one with the decrepit industrial landscape of the island, one of the most assertive exhibition sites in the city. Cockatoo Island’s history is one of violence, death, and the aggression of heavy industry. Art that is shown here has to be tough enough to deal with the context. One problem with Engberg’s catch-all curatorial vision is that she sees the island as “an imaginary, anticipated space ... a destination, a fantasy location, a fun-park; a utopia perhaps”. She sees it as light, when the reality is dark. A geographic misreading of space is perhaps why Randi & Katrine’s The Village is described as a commentary on the exclusion of refugees, although to Australian eyes it looks like a department store’s Christmas installation. All it needs is mock snow and Santa Claus.

Not every piece on the island is so out of place. Mikhail Karikis’ video, Children of Unquiet, installed in a creaky old shed, has children in an empty industrial landscape speak the words of the philosophers Antonio Negri and Adriana Cavarero. It is utterly compelling. There are some very good videos in this Biennale, mostly at Carriageworks where the installation ensures that each work is seen in a space that respects its individuality – while the poor quality of the overall lighting is an OH&S incident waiting to happen. At the MCA Pipilotti Rist has a multi-screen installation of incredibly lush sumptuous beauty while upstairs Douglas Gordon’s Phantom mixes an unnerving eye with pianos and the voice of Rufus Wainwright.

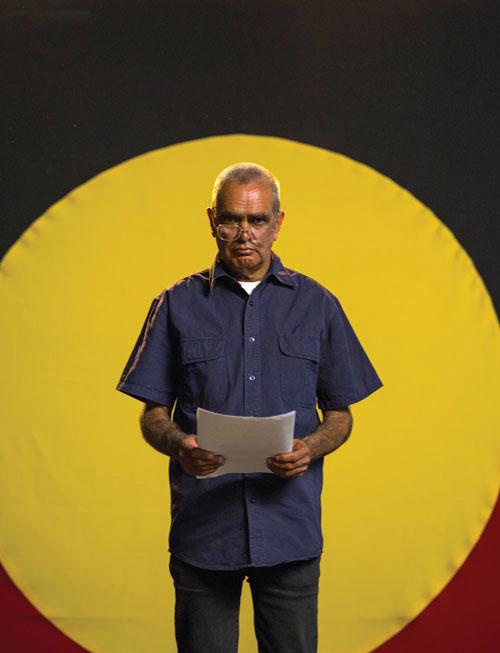

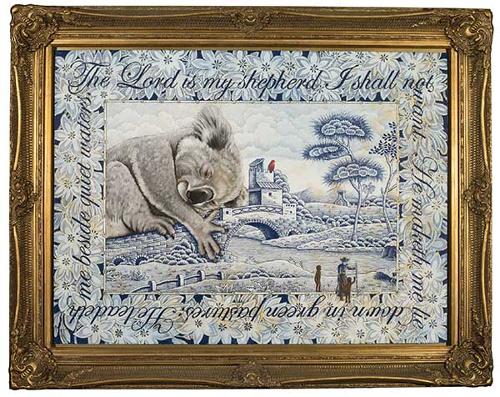

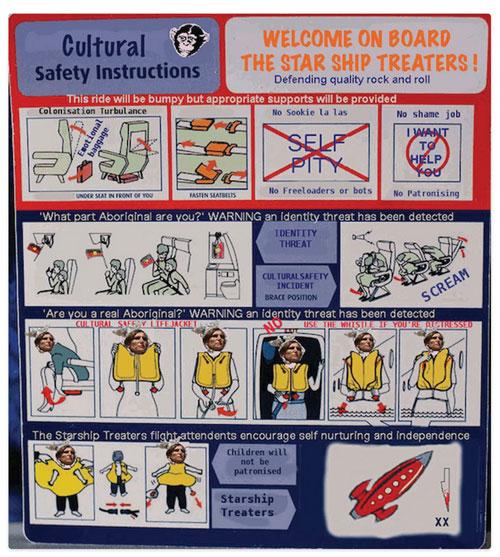

At the Art Gallery of New South Wales the space, and the well-schooled installation crew, make all the exhibits seem smooth, polished and inevitable. Bindi Cole’s We all need forgiveness, where Aboriginal people are recorded forgiving those European Australians who apologised for the crimes of the past, is countered by Angelica Mesiti’s heartrending lament, In the Ear of the Tyrant. Even more compelling is Mircea Cantor’s Sic Transit Gloria Mundi, a combination of video and installation that looks at the fragility and transience of life though fire and the remnants of exploded bullets. Some photographs, like Michael Cook’s digitally manipulated Majority Rule hold a message over and above beauty, while Yingmei Duan’s private wilderness installation gives both a song and a sense of the artist’s real presence.

But too much of the exhibition looks like a grab-bag, in the same way that Melbourne Now was a grab-bag. The difference is that Engberg had the world to choose from, that opportunity at least makes the Biennale of Sydney a more interesting exhibition. But it doesn’t give it a visual coherence. We need more from the Biennale of Sydney than a curatorial sampler bag.