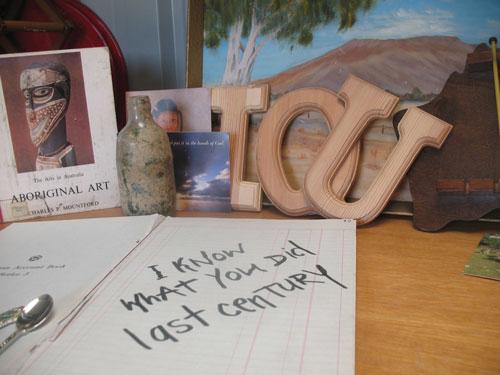

All that swagger and not a sorry in sight

At the beginning of his video work The Dinner Party (2013), Richard Bell is friendly and chatty as he walks through the crowd of people who are eager to meet him. The first question that he is asked is “So, what is it Richard, activist or artist?”, Bell replies “You will just have to wait and find out”.