SafARI, the independent, grassroots alternative to the behemoth that is the Sydney Biennale turns 10 this year and, under the direction of co-curators Liz Nowell and Christiane Keys-Statham, presents six different venues across Chippendale, Kings Cross and the CBD to varying degrees of success.

SafARI’s aim has always been to highlight and support some of the city’s lesser known artist-run spaces and this is admirably done with a confident sense of curiosity, particularly in buzzing Chippendale, but curatorially, SafARI 2014 is difficult to wrangle, with a great deal of emphasis given to the debut of a performance art programme rolled out across four of the six venues over three weekends.

For those of us who visited during the week, particularly the subterranean Alaska Projects, the lack of anything significant to really look at left you feeling like you’d arrived at the party after everyone else had left. Located down in the dank darkness of the Kings Cross Car Park’s Level 2, Sam Songailo’s untitled installation is almost literally the only light down there, after having awkwardly strolled the gauntlet of backpackers reading and cooking in their Combi vans at the erstwhile Sydney Travellers Car Market (an inadvertent addition to the live art calendar if ever there was one.) There was an additional small room given to Paul Williams and Christopher Dolman’s pithy ceramic musings on the mundaneness of studio life (think bongs and half eaten biscuits) but, as a whole, the experience here lacked coherent substance so it’s a shame to have not seen the performances by Frances Barrett or Linda Brescia. They could only have helped.

At The Corner Cooperative on Abercrombie St, the remnants of Kelly Doley’s performance Cold Calling A Revolution (Sydney Residential A-Z) at least gave some licence to imagination. Even without the artist there, systematically making her way through the phone book, cold calling people to ask them, market-research style, about their thoughts on revolution, the space and Doley’s methodical, quietly serious, wonderfully ironic work still felt intact enough to interrogate and appreciate. Other highlights at The Corner Cooperative included James Francis’s naïve portraits and Emma Hamilton’s delicate salt-encrusted landscapes set on and against blocks and tubes of glass. But again, as a whole, the works seemed incidentally put together and struggled to create any sense of a dialogue or identity specific to this actually rather lovely exhibition space.

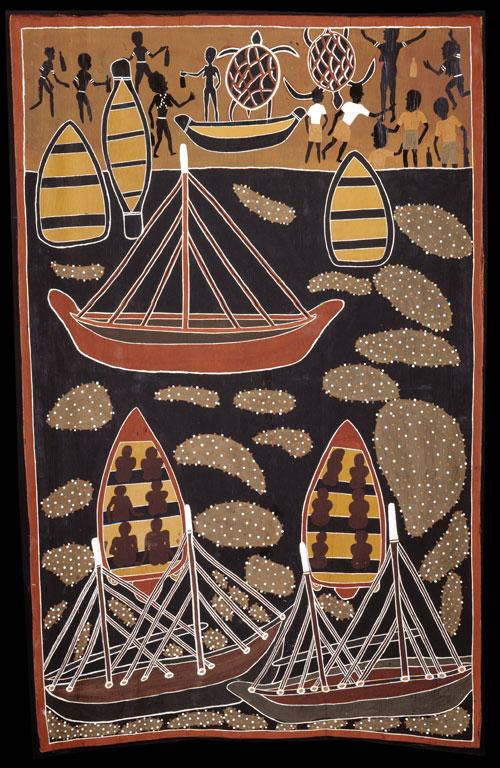

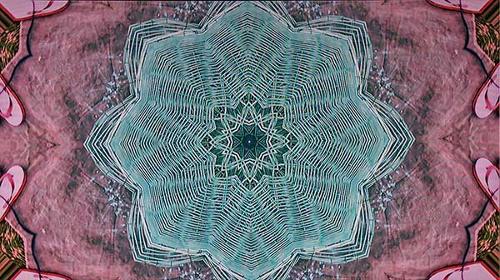

DNA Projects and Wellington Street Projects, also both in Chippendale, had singularly memorable works — respectively, Leyla Stevens’ two-channel video installation Ngendag/Rise Up (2010), a beautifully realised meditation on the role of the body in place-based ritual and community; and James Carey’s large, obsessively rhythmic pencil drawings. But that was about it.

Cross Art Projects in Kings Cross, showing works by Laura Moore, Dale Harding and Kate Blackmore and Jacinta Tobin in collaboration, felt the most curatorially resolved of all the spaces, exploring strong thematic ideas around physicality, lived experience, personal connection and Indigenous history.

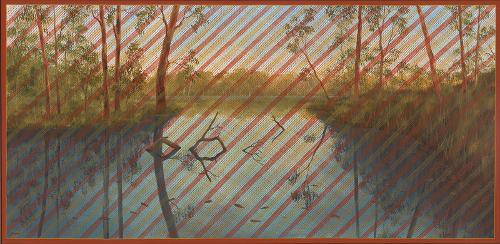

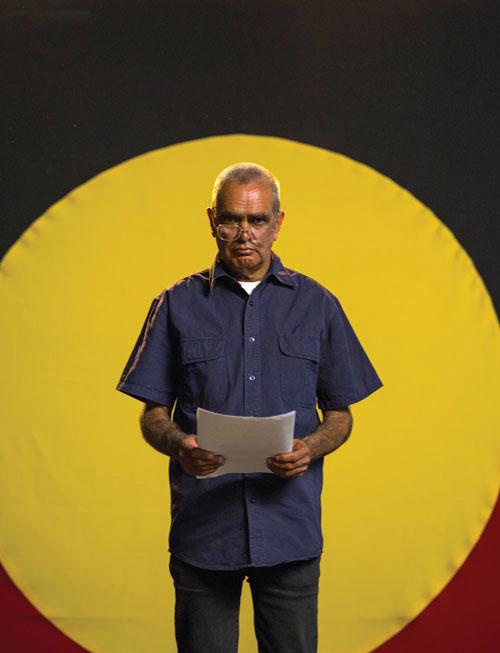

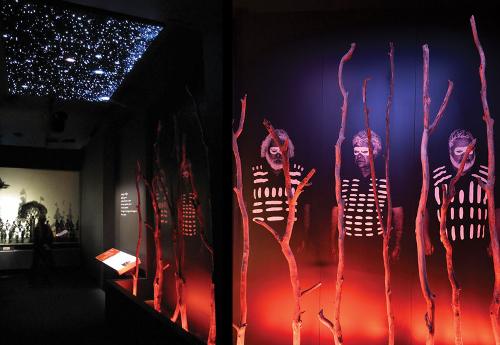

Laura Moore’s large-scale, darkly lit digital photographs capture fleeting moments of physicality as intimate portraits. The sunburnt traces of her swimming costume caught on her back; the tissue-delicate skin of an elderly man, his face cropped and obscured by shadow. They’re arresting images. Elsewhere Kate Blackmore and Jacinta Tobin’s work Ngallowan (They Remain) (2014) is an elegant and powerful visual exploration of Australia’s whitewashed history. Starting from W.E.H. Stanner’s 1968 Boyer Lecture on the “systematic failure of historians to integrate the story of Aboriginal dispossession” their dual-screen video work shows the blonde Blackmore on one screen dousing a blank room in white paint before then painting herself into obscurity, while on the left, a seemingly resigned but steadfast Tobin, in a red, black and yellow poncho, is shown sitting alone by a campfire with clapping sticks, occasionally appearing to glance, however accidentally, towards the woman on her right. Dale Harding’s restrained but devastating sculptural re-imagining of the horrific ‘punishment trees’ found on a number of Central Queensland Aboriginal missions also warrants mentioning here.

The sixth and final space, The Conductors Project in Museum and St James Stations in the city, proved difficult to locate.

It’s unfortunate to walk away from SafARI feeling largely underwhelmed as there are some genuinely engaging encounters to be had and the enterprise, supporting experimental, lesser-known art spaces and young emerging artists, is a critical part of the art landscape, and not just in Sydney. But there is a pervading sense, this time around, that some of the parts on offer are greater than the whole and the lack of a clearer objective of what that whole is, curatorially speaking, is certainly part of the problem. A significant live art program, while ambitious, has only shown up what’s missing elsewhere.

In introducing SafARI on their website, the curators talk about the exhibition’s now cult following, built from “the sheer love of the potential it represents”. Potential it definitely has, but it’s still not quite there.