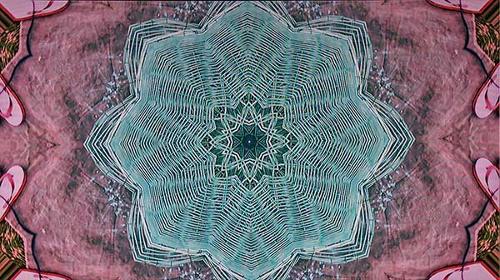

While editing this edition of Artlink Indigenous, several articles and blogs renewed my passion for identity politics, chief amongst them are Celeste Liddle’s piece in the First Nations Telegraph, titled, “Fair-skin privilege? I’m sorry, but things are much more complicated than that”[1] and Defender Of The Faith’s blog post, “But you don’t look Aboriginal.” [2] These texts along with the Abbott Government’s planned repeal of section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act which will effectively deliver free speech to bigots, all serve as strong reminders that Aboriginal identity and its kaleidoscope of shades, experiences and connections continues to be reduced to a one-size-fits-all approach by many non-Indigenous Australians.

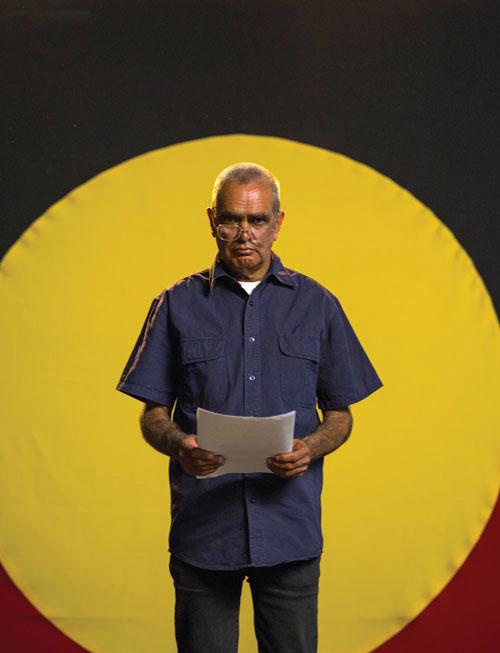

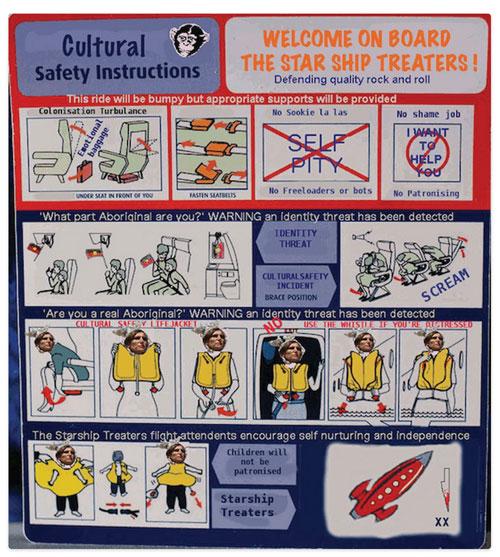

Among many people in mainstream Australia, the judgement of a person’s identity, and of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity in particular, is too often determined by the colour of their skin and/or by how much traditional knowledge they have. I know this from personal experience and from the stories of other Aboriginal people, including members of my family as well as writers and artists including Sharon Egan, Dianne Jones, Richard Bell and The Treaters – to name just a few. What is fascinating, when I’m not infuriated by this, is how strong some of these narratives continue to be, especially the narrative about the “real Aborigine,” which really gets my goat.

No one person will ever meet the full criteria of the unsullied “real Aborigine,” because this cultural type is a fiction and we live in the 21st century where access to and influence from all types of cultures is widespread, even from within our own multicultural families. Yet many of these fixed narratives about Indigenous Australians are firmly entrenched in people’s minds. But they don’t just stay there; they are manifest in thought and action, as in the following conversation that I have experienced time and time again (usually with men) illustrates:

“Where are you from?”

“Australia,” I regularly reply though I know what they mean.

“Where are your parents from?” they persist – my olive skin, brown eyes and hair are at odds with their vision of a typical Australian resplendent with blonde hair, blue eyes and pale skin.

Again I say, “Australia” and to put them out of their misery I add, “I’m Aboriginal.”

“Oh!”, they say with obvious surprise, then they blurt, “You don’t look Aboriginal”.

I smile or grimace, depending on my mood. And sometimes I politely reply, “No. I don’t.”

“How much Aboriginal are you?” is usually the next question.

“It doesn’t work like that,” I say. “If you are Aboriginal, you’re just Aboriginal.”

“We don’t use parts,” I hasten to explain. The “we” isn’t a reference to anyone in particular; it’s an inclusive, non-offensive and educational “we-apon” to stymie the use of quantifications like half- and quarter-caste, and full blood, terms which make me cringe.

“Can you speak an Aboriginal language?” This is often the last attempt to connect me with what they know about Aborigines.

“No,” I reply, “I grew up in the city.” This usually brings the questioning to a close.

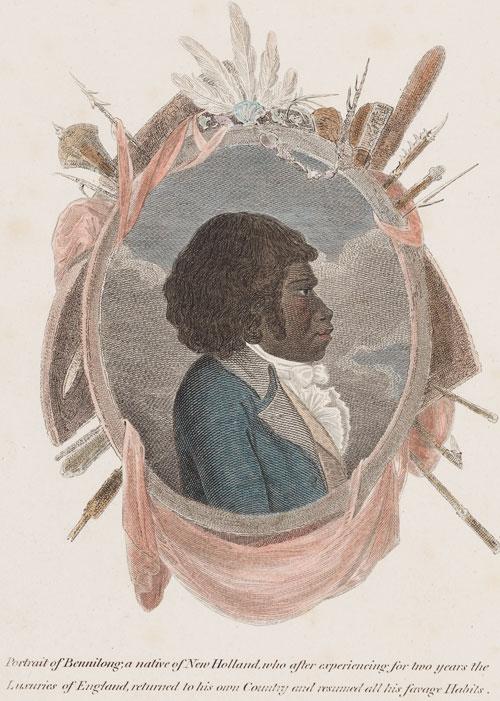

.jpg)

Although a reconstruction, this dialogue is almost verbatim of the narratives and subtle negations that I and many others experience practically every day. The unwitting subjugation of my cultural identity (and me) is embedded in the various sentiments and questions involved. In most instances, the person doing the asking is oblivious to these undertones. And as indicated, the “right kind” of Aborigine does not live in the city. I am not a “real Aborigine.” But nobody is and that’s the point, at least for me, of this edition of Artlink Indigenous – to emphasise, through art and story, the reality of Indigenous experience (plural), and to iterate that EVERYTHING is cultural no matter where you live, what you do or look like.

Over the last eight years, for my PhD studies, I have researched Aboriginal identity in urban centres. As a result, I am highly alert to the different ways that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and organisations reinforce the reality of our lives as Indigenous peoples. Art, literature, radio and television programs and advertisements, as well as blogs by individuals and groups like Deadly Bloggers (established by Leesa Watego) each exert truth over fiction.

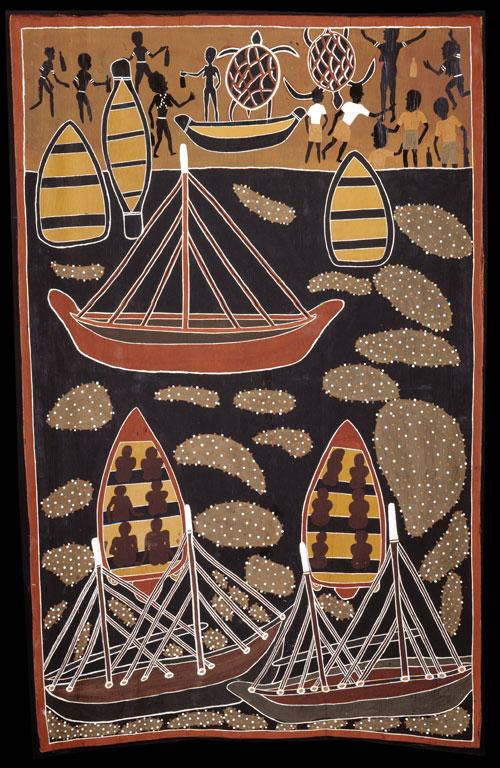

An intrinsic strength to these activities is that they situate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, culture and experience in the now, showing our relationship to a present which parallels and criss-crosses that of other Australians. For many, if not all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, our present also includes a living memory of the past handed down by family and community. The content that artists, authors, curators and organisations present showcases our individuality and diversity, as well as our connectedness inside, outside and across communities and cultures.

In minority studies the term “lived experience” is used to describe the first-hand accounts and impressions of living as a member of a minority or oppressed group. Sharing our lived experience is one of the single most important things we can do as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in this country. Our lived experience informs our identities in their myriad forms, just as much as our biological and cultural inheritance does. And every day it is our identity/lived experience that is being denied in insidious ways. By talking about our lives (read identity) we have the opportunity to present our selves, as we know them to be. It also gives people the opportunity to acknowledge us as we are.

To my mind, two likely outcomes must eventually unfold. First, if our lived experience is acknowledged our humanity must also be acknowledged. By this, I mean that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are accorded the fullness of the experiences of life – highs, lows, frustrations and joy, and creativity as presented across the articles in this magazine – therein releasing us from the role of distant “unknowable” Other. Secondly, if our identity is acknowledged; then so, too, must our existence as contemporary peoples living and breathing on black ground. While this can be difficult and intimidating, it is in our best interest to reveal our stories covering the full gamut of love, life and loss.

P.S. Thanks to my co-guest editor Glenn Iseger-Pilkington, the authors, artists, and trailblazers such as Tess Allas who was a guest editor of Blak on Blak with Daniel Browning who later became co-editor of the 2011, 2012, and 2013 annual special editions of Artlink Indigenous.

Footnotes