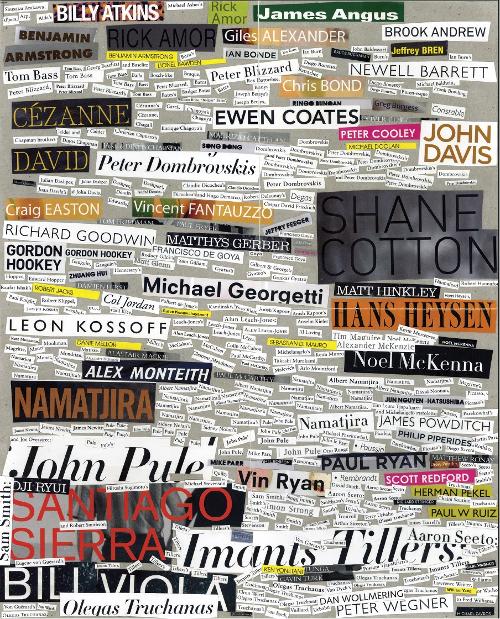

Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art has opened its largest exhibition of contemporary Indigenous Australian art My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia with 130 participating artists and 300 works that have been selected from its rich collection. Exhibition curator Bruce McLean has been the key to releasing these voices from the vault, and it is the Queensland voices that sometimes sing the loudest.

McLean locates three interrelated topics: ‘‘My country’’, ‘‘My history’’, and ‘‘My life’’ to convey our stories and experiences as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the Australian narrative. In an exhibition that is a celebration of diversity, McLean skilfully demonstrates the strength of the collection by creating new dialogues between familiar works and offering a transformative experience to an audience he acknowledges is predominantly white.

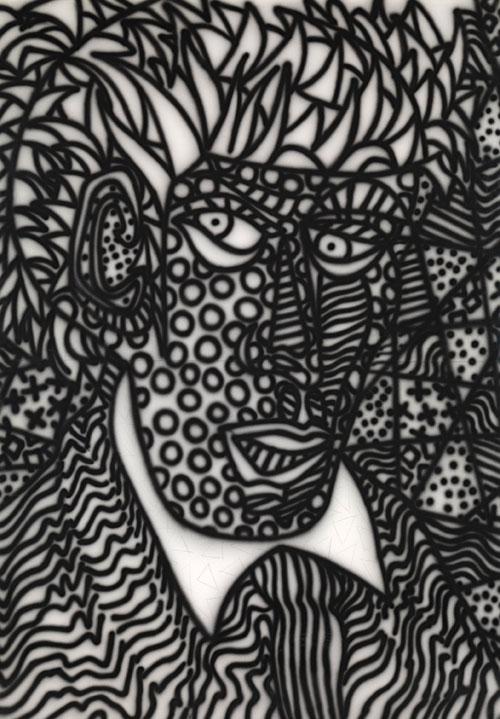

Reko Rennie’s vibrant Trust the 2%ers (2013), a monumental urbanised Kamilaroi dendroglyph specifically commissioned for this gathering ground, symbolically marks the entrance to the exhibition. Powerful and proud, this work also serves as a reminder that what you are about to encounter derives from 2% of Australia’s population.

The thematic backbone ‘‘My country’’ is located in the Long Gallery where significant works by senior Desert artists reclaim, reconnect and reaffirm connections to country. Twenty-six paintings are hung salon-style creating a visual map, a colourful feast of songlines crossing country. The sheer height of these walls demand that viewers must look upwards, making it hard to successfully engage with each work and get a sense of the important stories that are being told, passed on and shared here.

At the end of the River Room, decaled onto the windows, Megan Cope’s mesmerising Fluid Terrain (2012) casts a dot-dancing screen across the Brisbane city river landscape that lies beyond the glass. By restoring the traditional language place names on this outsized map, Cope immediately locates an Aboriginal presence in a reclamation of place.

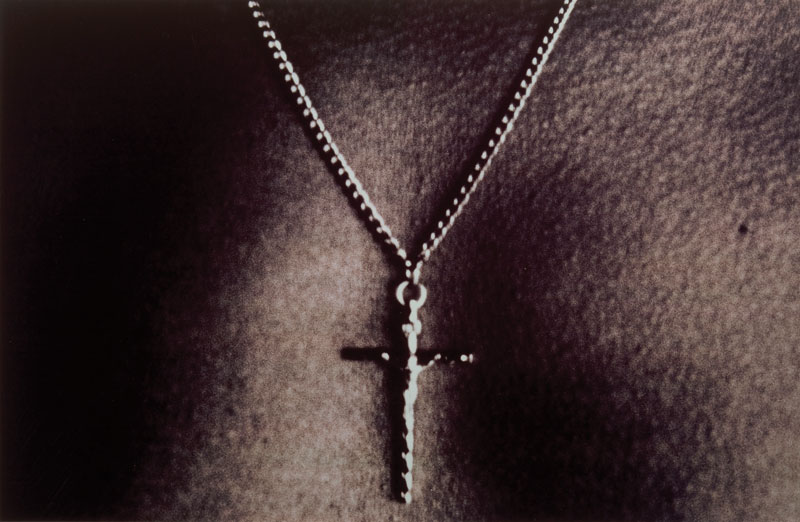

With a small singular work, Unnamed (2012), Dale Harding exposes the enormous mistreatment of Aboriginal people. At Worrabinda Mission, Harding’s grandmother was identified by the system as W38, and this code is beaten into the breastplate. With this cast lead piece Harding provides the historical context for many of the other works in the ‘‘My history’’ chapter.

‘‘My life’’ instantly references Kevin Rudd’s 2008 apology with bold text and Tony Albert’s Sorry (2008) is replete with kitsch ‘‘Aboriginalia’’. The artist has reversed Sorry since its 2008 installation in Contemporary Australia: Optimism, signifying the lack of any positive outcomes for First Peoples since the apology. Richard Bell’s I didn’t do it (2002), etched in black gravel on black, with the words ‘‘it wasn’t me, I am not sorry’’, echoes in solidarity.

The fraught issues that surround Aboriginal deaths in custody emerge as recurring themes. The soft pigments of Judy Watson’s canvas titled Memory Bones (2007) reference the sixteen broken ribs, and spilled blood of a young Palm Islander in 2004, the 147th Aboriginal person to die in police custody since the 1990 Royal Commission. Gordon Hookey’s Blood on the wattle, blood on the palm (2009), addresses the infamous events that occurred on Palm Island.

Vernon Ah Kee’s 4-channel video installation Tall Man (2010), which gathers together a number of strands associated with this issue to serve a punch that most keenly hits the mark. The artist orchestrates footage from mobile phones, cameras and newsreels on the day of the uprising to surround you with several viewpoints. This work delivers the impact of that moment when the authorities announced their whitewashed decision that the Palm Island death in police custody was the result of an ‘‘accident’’. At the conclusion of this video the tension in the darkened room is palpable leaving an overpowering silence that serves as a reminder of W.E.H. Stanner’s description of ‘‘The Great Australian Silence’’ that has attempted to render mute so much Indigenous history in this country.

As at any great gathering there are festivities, uniting voices, exchanges of information, and lessons to be learnt. The artists in this exhibition speak intimately about their lives and why they still call Australia home, creating challenges for viewers who make the effort. McLean has convened a meeting place that needs attention and respect to absorb all that is on offer. Some works scream at you, some creep under your skin, but all relate real stories, real experiences that need to be told – whether whispered, sobbed or shouted.