Since moving to Canberra I have changed two of my critical preconceptions – firstly through hearing Patricia Piccinini talk about her work at the ANU School of Art and secondly, through visiting Cold Blooded, a survey exhibition of the work of eX de Medici. Both big-name Australian artists with connections to Canberra have been invoked as part of the Canberra Centenary celebrations. The shift in my perceptions of their work is characterised by a moving away from the obscene explicitness of the high impact towards an aesthetics of care, a more difficult and multilayered gravity.

The themes of death, seduction, fragility and obscenity have long been present in de Medici's work. Viewing so many of her paintings together in this survey, different themes and reactions started to emerge. The exhibition is split into four rooms featuring de Medici’s recent Iranian inspired work; her Vanitas paintings; her gun series and earlier works that evolved from her long-standing artist fellowship at CSIRO Division of Entomology. These series overlap and inform each other. The moth wings invade the weapons and the plant motifs of the Vanitas paintings grow from the guns.

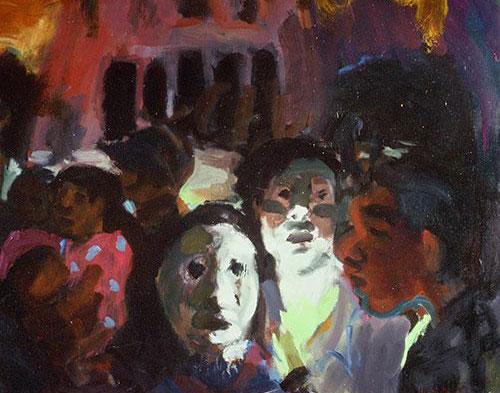

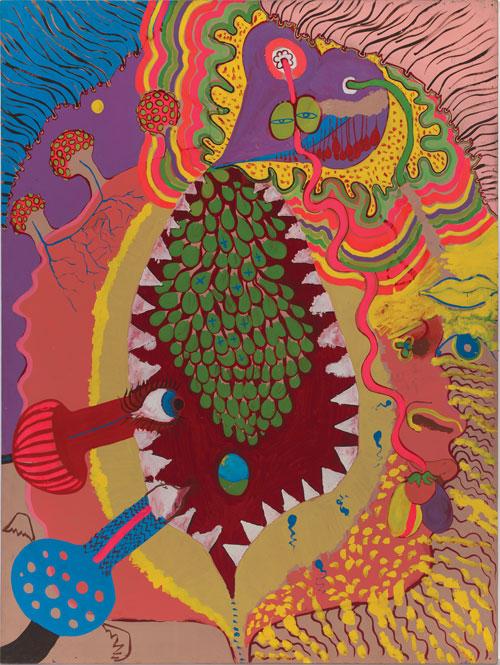

de Medici’s Vanitas paintings do not present life decaying in the orderly manner of Dutch Vanitas, rather, they are crammed with the clutter of greedy, power-hungry lives. In their busyness, the frames filled with juxtaposed images, they speak of life spilling over, overflowing into the inevitability of death. They are demanding, they ask the viewer to keep looking for connections, for realisations; they ask for time. Time is a significant factor in de Medici’s work; the time that the works take to paint, and the time it takes to view them. Time correlates with care, she is asking us to take more than the flickering moment of viewing, to take more care of how we see.

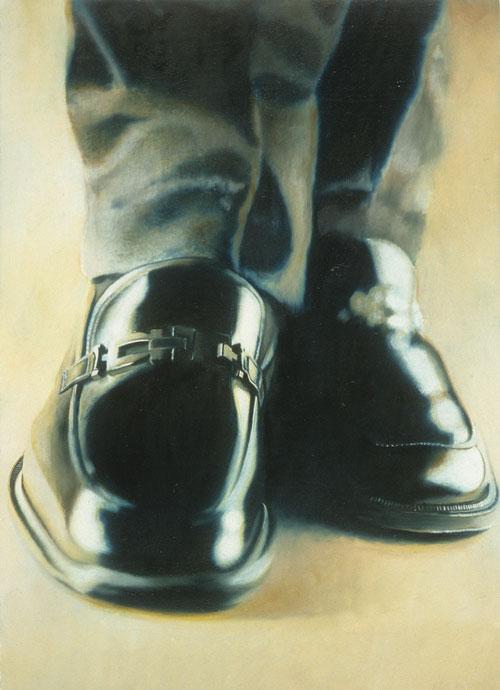

She presents a world where the soft pelt of death has already crept its way into everything. Guns, implanted with the highly patterned scales of moths, are solid and alive in her images, but could soon crumble to dust as dead moths so readily do. The tension between the cold hard guns and the microscopic surfaces of moths maps out the corresponding tension between life and death, but also points to a greater complexity that is less about the inevitability of death and more about the responsibility for life.

The moths that de Medici studied for these works are species that have not yet been classified and that may be extinct as they are from areas where mining had destroyed local ecosystems. In one of the catalogue essays, Marianne Horak, a taxonomist from the CSIRO who worked alongside de Medici during her residency there, writes that the moth paintings also function as a celebration of the beauty of the moths that they both studied. There is a textile-like quality to de Medici’s markmaking; the small patterns of moth scales that cover a skull or a gun evoke the beads of a woven cloth adding a tactile quality; the excess of floral motifs pushed against the surface of the paintings evoke the tapestry and cloth designs of William Morris. There is a sense of familiarity produced by textiles, what becomes startling then, is that I want to stroke this moth-gun, to hold it close.

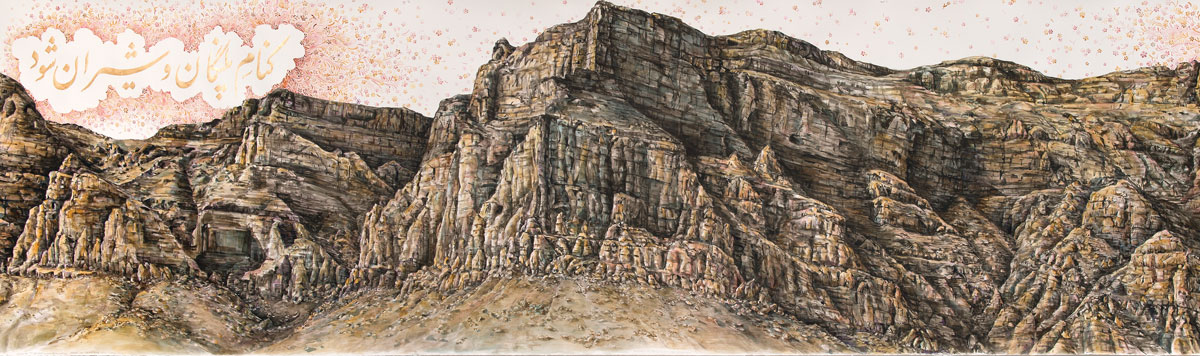

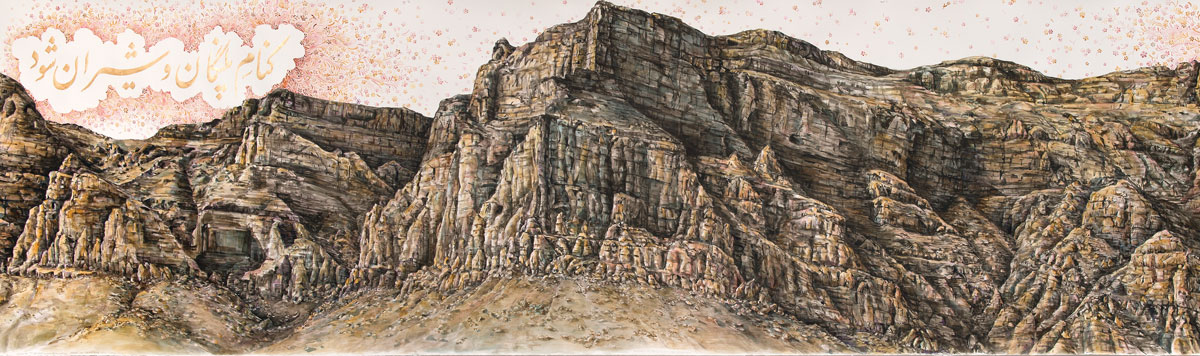

In her most recent work de Medici has taken her inspiration from her many visits to Iran. One of the most striking works of this series is Real Estate, a five-metre long unframed painting of the stark Shir-Kuh Mountains in Yazd, a place close to the heart of Persian people. This work is a collaboration with Master Calligrapher, Mahmoud Rahbarah, who painted the illumination across the sky. The viewer is dwarfed by this harsh landscape; it is presented as an un-enterable place, as unreadable as the Persian text. This sense of alienation highlights the othering of Iran, repeatedly ‘demonised’ by the Western media.

de Medici’s works are often described as shocking: the viewer is seduced by beauty only to be stunned into recognition of the paintings’ true subjects. Viewing all of the works together in this survey this sense of shock is neutralised, much in the same way that the saturation of media images that she critiques tends to be. For me, what emerges from these highly complex paintings is not their capacity for trauma, but instead a slowing down of viewing which leads to an aesthetics of care; I am touched.