For quite some time now, the daily life of John A. Douglas involves a scheduled period of time hooked up to a dialysis machine due to kidney disease. It is a private ritual performed at home and so embedded in the fabric of his everyday existence and quest for survival. Millions of others are in similar situations - indeed disease is something we all face everyday. Yet, the aesthetics of disease and its associated rituals are shut off from view, walled off due to discomfort and fear. Douglas breaks down this wall; to an extent he erects his own fleshy body in its place as a visceral conduit through which intersecting narratives about transformation, spirituality, and otherness co-mingle with the fluids that renew his ailing organs.

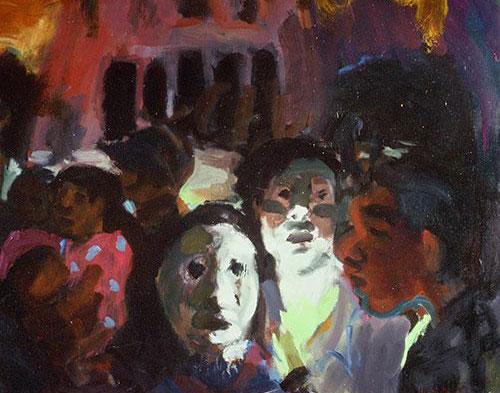

A private ritual rendered public through the conventions of durational performance, Douglas offered himself up at Performance Space for Body Fluid II (redux) as a spectacle in ten-hour lots divided into seven cycles each comprising a period of one treatment that he undergoes each day. Fitted out in a lycra gold bodysuit, Douglas was positioned in a cavernous space on an altar-like platform, his Buddha-like body suggestive of a long-gone deity entombed in precious metals readymade for worship. That is, until he started moving around and interacting with the space, seemingly oblivious to an audience. The tube connected to his body was a constant reminder of his enslavement to the maternal machine whose umbilical cord offers both nourishment and punishment.

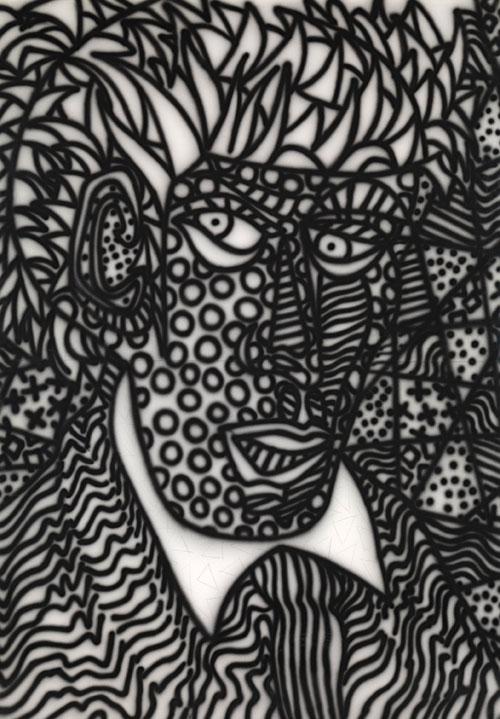

Renowned as much for his atmospheric video works as he is for durational performance, Douglas optimised the theatrical experience through epic projections that flesh out (so to speak) the relationship of the body to the landscape – the stranger in a strange land. Nicholas Roeg’s film version of Walter Tevis’s 1963 novel, The Man who Fell to Earth (1976) is the most obvious reference point here. Cast as the alien in his own videos, Douglas navigates an indifferent, difficult terrain. Alone in an unpopulated landscape his otherness can only be known to himself.

Installed in an adjacent gallery Douglas’s new four-channel video, The Visceral Garden similarly packs a punch. Viewing it required a perceptual recalibration after experiencing the impact of the live performance. Over four screens, the gold-suited alien is now a blood clot red figure located within a psychedelic ‘garden’ of bodily organs. Rich in colour and texture, imagery of the body’s otherwise unseen interior stuff (sourced during an artist residency at the Museum of Human Disease at the Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales) is digitally composited to create an otherworldly landscape.

Described as a ‘‘narrative journey divided into four sequences’’, Douglas orbits throughout this space, the weight of earth-bound gravity dispensed for an underworld free-fall through portals of blood, forests of bones, membranes of tissue and rivers of blood. While the artist’s live dialysis performance emphasised treatment for disease, The Visceral Garden sees ‘‘disease itself made manifest’’.

Body Fluid II (redux) was an extraordinary achievement, bringing together an aesthetic and performative language unique to Douglas. While he operates within a tradition of artists who have made art of their illness (among whom the late Bob Flanagan seems his most direct ancestor) Douglas sits alone. A younger generation of Australian artists have become almost obsessed with mining the conventions of durational/endurance performance, yet often it speaks more to their own narcissism (“you will look at me for 10 hours!”) than it does of any attempt to make something genuinely meaningful of the medium.

The power of the work of John A. Douglas is that he is reminding us of his own tenuous mortality – indeed our own – in the way that private medical ritual is rendered public spectacle. Corporeal interiors are hurled into an exterior world where the artist can project the course of his existence as grand gesture, knowing the reality of disease is as painful as it is banal. It is in this space between the knowing and unknowing of what is to come that we see the artist’s evisceration transformed into a thing of absurd beauty that lasts in the laughing face of decay.