Painters were put under extreme pressure in the 80s and curator Max Delany captures the semiotic struggle vividly in his first show at the National Gallery of Victoria. The decade was one in which critical theories forced artists to argue their positions and it is fitting that the first painting in the show is Victory by Robert Rooney.

This finely-executed work with its pastiche of text, images of fighter planes and needles drives home the point. Critics and language theorists were using structuralism, a potent new narrative theory that saw art as a language governed by oppositions, to make way for something new.

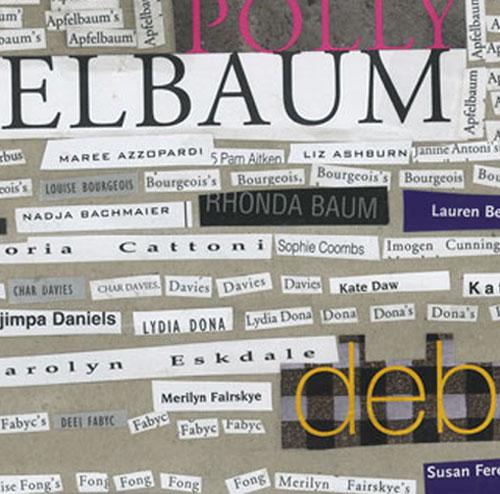

A suite of works by John Nixon follows Rooney’s opening salvo, combining Malevich’s cross with a range of readymade items, prominent amongst them is a mallet. The structural toolkit for the 80s artist also included clamps, protractors and hammers, if Richard Dunn’s Tools of Coincidence is anything to go by. In the universe of discourse, every element becomes a working part for the production of meaning. It is up to the reader or viewer to make something of them.

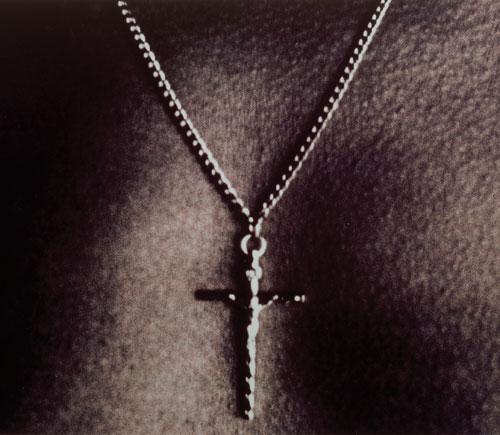

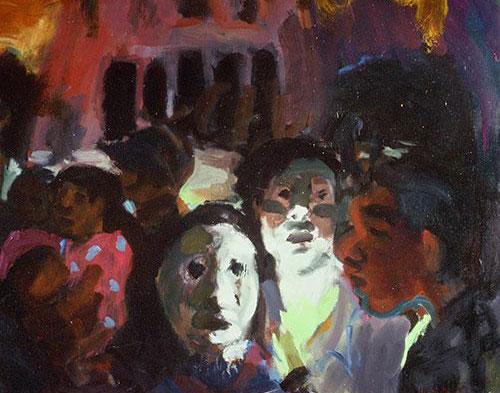

Delany is a serious scholar and his didactic boards capture the way meanings were excruciatingly constructed in a decade that tends to be swamped by readings that are either nostalgic for cultural detail or make passionate pleas on behalf of painting. He lets the conflict unfold slowly by counterpointing a range of Neo-Expressionist paintings on large canvasses against some hip graphic works. Album covers by Philip Brophy and Maria Kozic and scenes from fables by Vivienne Shark LeWitt illustrate the penchant for appropriation, and The curtain torn by Brent Harris shows the way deconstruction could be used by artists to penetrate taboos, in this case the temple veil used after the death of Christ.

Prior to the critical discourses of the 80s, Dale Hickey’s Pal and Pilchards would have been deemed a ‘‘good’’ painting. It is large, bold, ironic, self-reflective and expressive. The fact that it depicts the mess on the painter’s studio floor would have been deemed irrelevant. At stake were issues related to the movement of the viewer’s eye around the canvas and the handling of paint. Perpetual motion machine by Gordon Bennett, on the other hand, would have been deemed ‘‘bad’’ for taking an obvious narrative stance on a social issue. The arrows and didactic posturing of displaced indigenous figures would not have accorded with the aesthetic principles of the modernist.

Postmodernism changed the balance of power between maker and viewer. By showing that all meaning is constructed, the new theories gave writers and critics the language for toppling old supremacies. The assault was successful. From today’s perspective, indigeneity is a mainstream issue whereas the individual painter in his messy cell has been driven underground. New Romanticism was one ideology painters adopted to deal with the critical environment. Sections of medieval walls and decorative details were blown up and repeated. These works look like weak wallpaper designs next to the narrative power of Tracy Moffat’s now classic photographs.

Delany’s clever walk through the decade creates a dynamic and rare opportunity for contemporary artists to view the battleground between the self-referential practitioner and the artist who was more inclined to examine the frame as well as the work. Narelle Jubelin’s Trade delivers people #2 suggests an elegant solution to the problem. Her frames are deeply carved in timber and stained dark, connoting both Pacific adventures and Edwardian solidity. A respect for craft and collections of items shows the way aesthetic systems operate to frame content. Trade is a two-way street, the one influencing the other and vice versa, subtly challenging notions of authorship and originality.

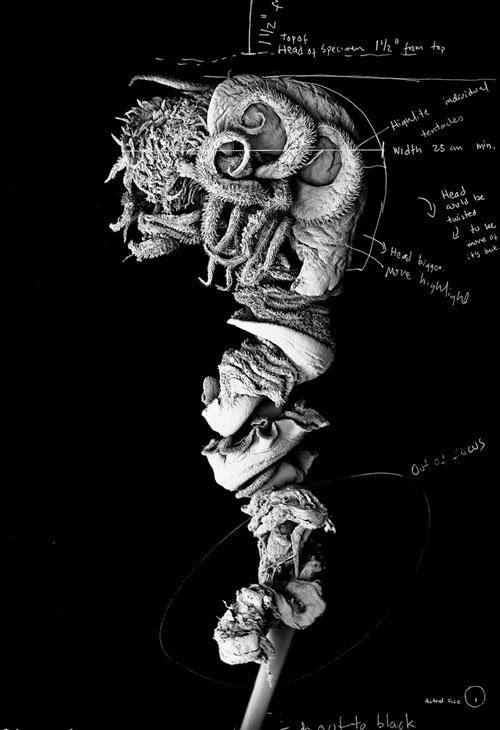

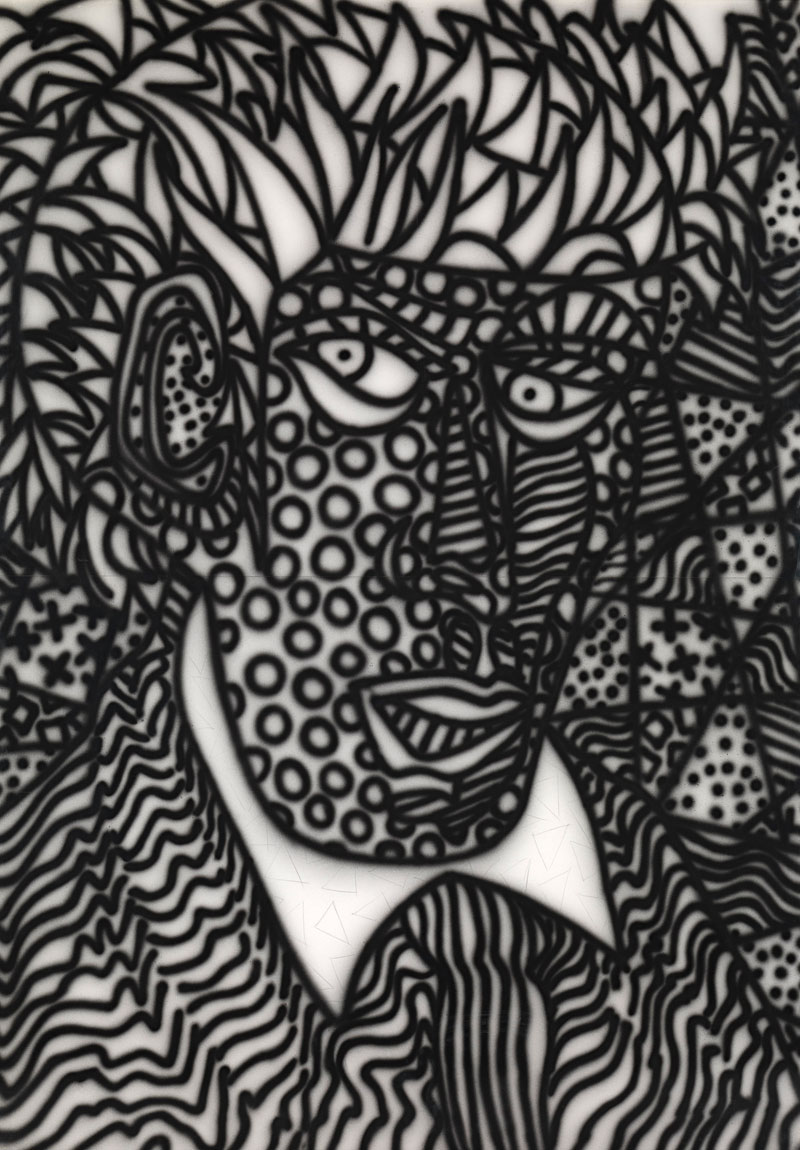

On the final leg of this journey through the argumentative eighties is a narrow corridor where Peter Ellis has managed to squeeze a Léger ladder, Giotto angel, Guston cone and Boyd head into one busy work. Jon Cattapan’s renditions of his inner state following the death of his sister play a rare mimetic note in this land of the stance. An etching by Tim Jones, High Aspirations in Boxwood Road, seems to say it all. Works after the 80s became contested sites. They aimed to make a rhetorical point that could be deduced by the viewer. Painting would never be the same again. Howard Arkley’s spraycan masterpiece Tattooed head remains a fitting emblem of what happened to those who became trapped in this logocentric world.