From outer space, the view of human life on earth – perhaps from the position of other sentient beings – might appear similar to the view through a microscope of XX and XY gametes transforming into a zygote in a petri dish, dividing and multiplying. The male and female of the species copulate to produce young, who in time copulate to produce more offspring and take up more space in the world. It’s a simple biological perspective, and one that eschews notions of family, community, society, race, politics, religion, nationhood, work, emotion and love; the constructs through which we individuate ourselves and create meaning and connection in our lives. The biological perspective on gender and sexuality, however, is still the dominant, global perspective – reinforced in its place by religion, legislation and entrenched social codes.

The past few years of mainstream cultural and political discourse in Australia have increasingly involved statements about gender disparity: from calling-out the misogyny directed by news media oligarchs and conservative politicians towards our first female Prime Minister (in her shortened term in office), to reporting on increasing pressure from the social and political movement seeking marriage equality for same sex partners. Writers, thinkers and activists across Australia are bringing the endemic presence of everyday sexisms and gender discrimination to account; on the street, in the workplace, in sporting culture, in education, in parenting roles and in the highly visual consumer landscape. But these very public examples are only the tip of the iceberg, with the past ten years of artistic, academic and museological practice interrogating gender, identity and sexuality in deeper ways – splintering out from the binary positions created by the second-wave of feminism in the 1970s. In this edition of Artlink, ‘‘Sexing the Agenda’’, Joanna Mendelssohn and I have tried to fathom some of these perspectives in Australian contemporary art, to consider narratives, ideas and practices around gender identity and sexuality that aren’t necessarily headline-making, but that seek to question our cultural foundations, challenge the construction of biological gender as the societal norm, and investigate the ongoing empowerment of the white, patriarchal system that controls our lives.

As the co-curator of a recent festival investigating Australian culture through the lens of sex and gender – SEXES (2012, Performance Space) – I am more than aware of the impossibility for platforms such as this to be totally inclusive. They are, by their very nature, discriminatory, as is the editing and curating process. Fortunately, we are not alone in our investigation of this topic, as simultaneously other art journals and arts organisations as well as queer publishers are presenting their own, differently-voiced perspectives.

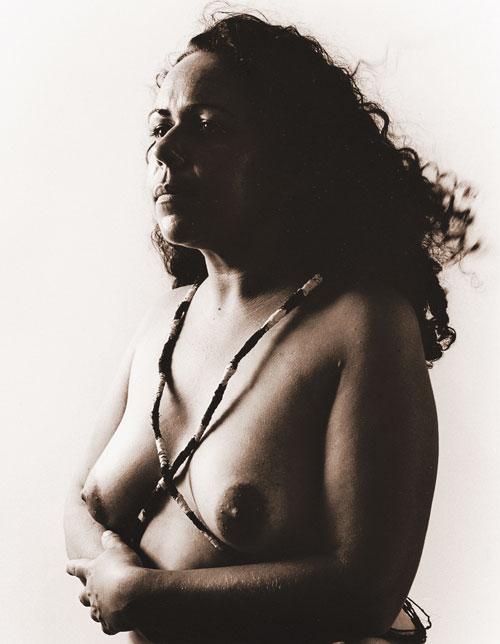

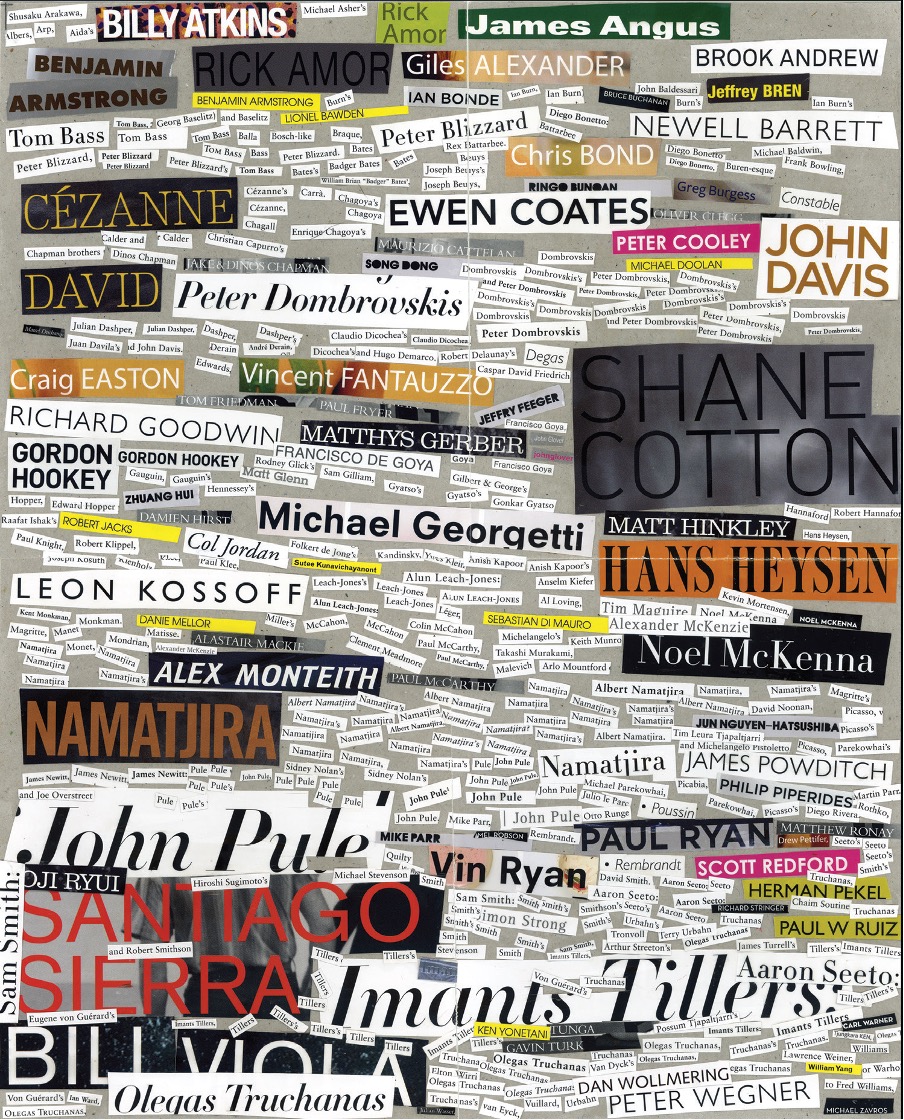

For my own thinking, Australia’s problems with gender discrimination arrived with the First Fleet, with convict settlement bringing fifteen men to every one woman. And from thereon these issues became entrenched through the patriarchal institutionalisation of most of the inhabitants of the land, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal in prisons and homes of Church and State. The rawness of emotion around the Stolen Generation in particular, as well as forced adoptions and the incarceration of ‘‘wayward’’ women is because these things happened in living memory, and survivors are still fighting for recognition and compensation for their treatment. Our issue throws a spotlight on some of these uncomfortable histories, with writing about the intersectional practices of Indigenous female artists by Odette Marie Kelada and Madeleine Clark, and an interview by Lily Hibberd and Bonnie Djuric with women artists and previous inmates of the Parramatta Girls Home. The performance of gendered identity is surveyed by Laura Castagnini, while trans artist, academic and activist Regrette Etcetera questions who is this performance for, and why? Concepts of partnerships and the constitution of the Australian family unit are investigated in the art/life marriage of Ms & Mr and through consideration of Deborah Kelly’s ambitious photo-portraiture project The Miracles (2012). And of course, there is Feminism and its legacies, which is among the reasons we have a platform for this edition in the first place. Flanking our editorials is artwork especially commissioned for this edition of Artlink by Elvis Richardson, AKA CoUNTess, who presents a collage of male and female artist names, cut from the pages of a 1998 edition of Art & Text and a 2010 edition of Art and Australia.

The title of this edition of Artlink is, of course, borrowed in part from Jeannette Winterson’s novel, Sexing the Cherry (1989), a space-time, epic search of the self. In this quote from a radio interview in 2012, Winterson expresses the inverse of a biological perspective on sex and gender – hopeful and filled with the possibility of change.

I’m not sure we need to be naming difference. I think we need to learn how to love and accept each other ... it seems to me that what we need to be able to do is to concentrate on how to develop our humanity.