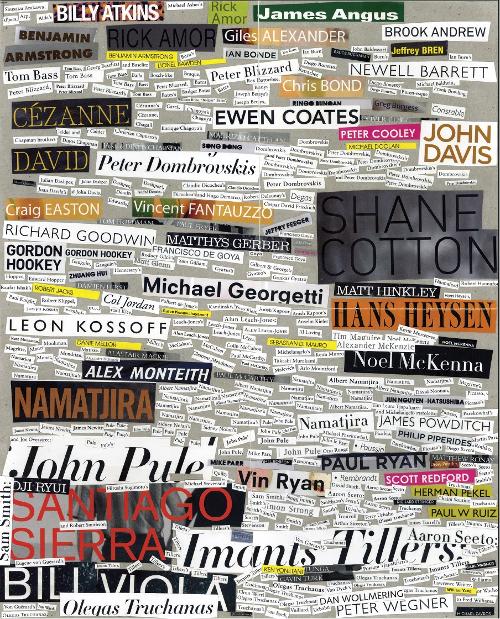

Heartland is a diverse exhibition featuring 45 artists, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, who have helped re-shape alternative and pluralist representations of belonging in this State. The notion of belonging to one’s Heartland runs thematically throughout the exhibition.

Connection to a place is a social and political practice, and one that is contested, as demonstrated by Wendy Fairclough’s Commonality (2010). She employs the theme of belonging by dissolving the things that separate us and focusing on the things that connect us. Her four lead crystal brooms signify the ways we are all bound by domestic rituals, as an enactment of belonging by caring for one’s place, and also representing the four ‘‘super powers’’ (India, China, the UK and USA) to connect the broader themes of economic imperialism and its effect on people’s lives globally.

Stewart MacFarlane also mixes metaphors in his figurative piece Transcontinental (2013). Thematically his work challenges homogenous identity constructions through the reading back of alternate representations of belonging. Ian North’s work similarly engages visual conventions driven by considerations of place in Felicia: South Australia 1973-1978. The 38 prints ironically evoke Felicia (happiness) and were taken during the Dunstan era. They consist of uninhabited landscapes illustrating the silence in this purportedly Festival State. Similarly, Kate Breakey’s embellished photographs, such as Hole in the Sky, Meningie South Australia (1980) conjure memories of road trips throughout South Australia where blue skies merge with deforested ploughed red earth. Kim Buck’s astounding charcoal on paper drawings also conjure these spatiotemporal landscapes.

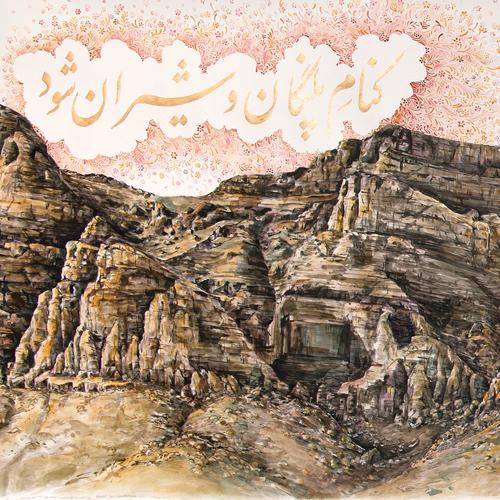

Angela and Hossein Valamanesh’s work evokes belonging through connection to one another as opposed to Amy Joy Watson’s considerations of the way we affect the spaces that we occupy in her sensitive balloon forms that drift when viewers move past the work. Annalise Rees’ work also talks to the shadows and spaces in-between in her architectural constructions.

Chris De Rosa draws on notions of belonging in Artificial Kingdom (2013). This creative feat is less concerned with an environmental statement as such, but more a focus on the splendour of nature. De Rosa draws from her Italian heritage the art of lacemaking and re-constitutes these seaweed/lace pieces based on her nature findings along the southern coastline. Belonging is figuratively created through the use of symbology that pervades these magnificent vertical pieces, including the lovers’ legend of lacemaking from Burano in Venice, as well as themes of gendered occupations and the art of lacemaking prescribed by missionaries to colonised peoples.

Yhonnie Scarce directly addresses colonialism and its corollary Social Darwinism in her Not Willing to Suffocate (2012). The line of 60 blown glass bush bananas in laboratory flasks is a memorial to the unbroken line of the heinous crimes of racialisation. Whilst Paul Sloan’s work also refers to colonialism and its aftermath, his position comes from a settler perspective and attempts to engage with symbols of cultural context and exchange, particularly in Planet Caravan (2013).

Settler themes of belonging through the employment of a land ethic of care is well- presented in James Darling and Lesley Forwood’s collaborative piece Country (2011) which includes 3.5 tonnes of mallee roots. This detailed representation of the lower Murray Darling Basin is a political and environmental protest against the maladministration of natural resource management in this country. Philip Samartzis’ soundpiece of waves crashing accompanies this caringly crafted sculptured landscape. However, this representation stands in stark contrast to the bright and explosive Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands artists’ works that also address belonging and the practice of Caring for Country.

Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara artists are from Amata and Ernabella. Paarpakani (Take flight) are figurative birds accompanied by Tjanpi punu (grass/trees) made by nine senior Anangu women. These large birds are healing birds that have been healing communities for 1,000s of years. The hues and vertical lines found in the collaborative men’s work led by Hector Burton called Kulata Tjuta (2013) are not only reflective of Country and connection to home, but also of the revival of spearmaking led by Burton at Amata; an enactment of agency towards recovery and healing from the impact of government interventions and structural inequality in this country.

This exhibition is instructive and cleverly presents pluralist representations of belonging. The various standpoints do not annul each other, but instead instruct the viewer to re-assemble new ways to understand our Heartland and our ethical responsibility to care for the places that we occupy.