‘‘If you were to live here...’’ facilitated exchanges about home and belonging in an ever-expanding, transitional and globalised world in works dispersed over nine locations by over 30 national and international artists. It is a pertinent and inclusive theme, and I assume a certain dissonance of voices, with the unmelodious sound of rigorous debate prevailing over polite conversation. Its curator Hou Hanru describes the intent of the Triennial as being to expedite social interaction ‘‘between artists, people and the city to envisage possible futures”.

Hanru’s questioning of being or becoming located, living, and ultimately searching for a place to call home, is presented predominately through the medium of institutional space. Not being an Aucklander, I walk the city, clutching my Triennial map and it seems appropriate, somehow to feel a sense of being alone. I see the flags of the Auckland Art Gallery immediately and make a bee-line up the hill.

Becoming frustrated as I walk through one gallery after another, comparing names on the Triennial map to those on the wall, I eventually tire of the hunt and head back to the shop to purchase the $42 catalogue. From this I am able to glean that the works are interspersed through the galleries and, using the images as a guide, I slowly begin to encounter each artist’s contribution. There is an inherent contradiction in visiting these privileged spaces to gaze upon the spectacle of displaced minorities, scenes of poverty and isolation.

The space of the art institution highlights the distance present between the art audience and the people discussed and/or represented. This raises questions of who the Triennial is for and what this conversation is really about? In analysing my own discomfort as a relative insider – as someone situated within the ‘‘art world’’ – I am reminded of Andrea Fraser’s 2005 Art Forum article From the critique of institutions to an institution of critique in which the institution is conceived as a “social universe”. In this sense the gallery/museum becomes a container for social relations that are performed, in which experiences or encounters are dependent on a complex set of actions, gestures and gazes. In his 2011 book Social Works: performing art, supporting publics, Shannon Jackson presents the institution as performed, revealing “the institution to be less an object than a process, less static than durational, less a sculpture than a drama”. If the institution can be positioned as performed and embodied then have the repetitious actions of the institution transformed to accommodate Hanru’s vision?

Proposed as a “site of production” or “a kind of open university” The Lab is posited as a site of resistance “mirroring the strategy of Occupy”. Located at the Auckland Art Gallery, The Lab is discussed as a central base of dialogue and debate around five major themes: Rural-Urban (as living space), Emergency Response and Recovery (Christchurch as a case study), Multicultural Impacts on Urban Transformation, Ideal Homes and Informal Markets. Although it seeks catalytic outcomes associated with the formation of a living, evolving workspace, The Lab is problematic and I find myself questioning whether the performative actions of the institution are overcome to the extent that it could enable the engagement of those for whom the questions of the Triennial seem most pertinent. Hanru speaks of the art gallery or exhibition space as an environment which can be transformed into the space of “real life” where artists become inhabitants of a “real home” in which new conceptions of social spaces, relations, and visions are possible. The transformation of the art institution presents a number of challenges within this discussion. Can any transformation or intervention into the institutions physical spaces constitute a shift into ‘‘real life”?

.jpg)

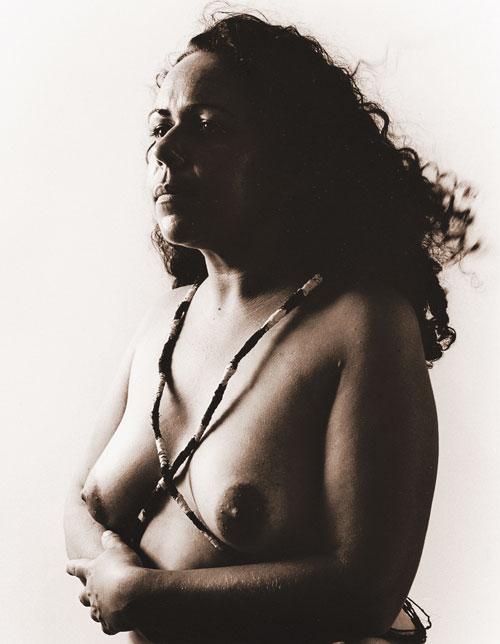

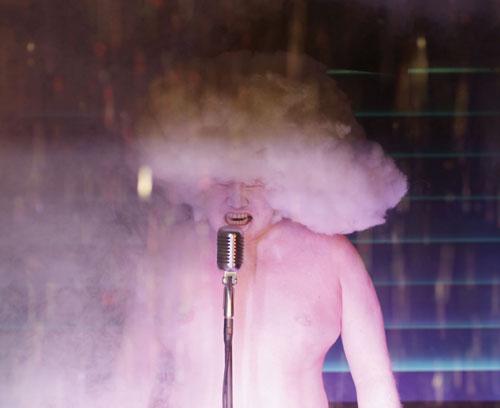

Ho Tzu Nyen’s The Cloud of Unknowing (2011) situated at St Paul St Gallery, exemplifies the Triennial’s discontents. Its portrayal of fragmented glimpses into the lives of eight people inhabiting an aged and apparently forgotten apartment building satiates the very human desire to see without being seen. Sitting in the comfort of the darkness I am presented with a series of exotic curiosities: people living in isolation, in poverty, afraid and seemingly without hope. The space is permeated with the sound of breathing that begins slowly and becomes increasingly rapid charging the space with a sense of dread, of something about to unleash a destructive force which is beyond the control of those trapped inside.

Scenes of dilapidation – water flooding under doors and raining though ceilings, filthy bathroom sinks and rotting plates of food crawling with maggots – are accompanied by rhythmic drumming. A terrified hoarder, illuminated by hundreds of bare bulbs seeks refuge amongst his treasures. A woman searches for a station on a radio that emits a cacophony of voices and static. A man sits at his desk surrounded by books shelves, writing frantically by lamplight. Urgency pervades the space. A ghostly figure with clouds around his head stands theatrically at a microphone, his screams echoing through the building as a smoky white cloud – a kind of emptiness, begins to envelop and erase everything and everyone. It pours out the window of the apartment where a lone voyeur stands transfixed.

Those on the streets outside the apartment remain oblivious to the noise and desolation within, and the casual chatter of passers-by and the laughter of children can be heard. Something has been lost, as I watch from a comfortable distance – entertained but largely indifferent. If I was to live here, I wonder, would my voice be heard? Would anyone notice if I found myself alone, disconnected and displaced? Can those on the outside ever be brought inside in order to engage with issues about identity and belonging? How can I, as an insider, truly gain an insight or way of knowing that has any relationship to those represented? In this respect I leave the Triennial full of questions that unsettle and disturb me, that stick with me as I feel the relief associated with heading home to a place where I feel I belong. It could be said that this is what great art does, it leaves you troubled, it leaves you with an empty space in which uncertainty lingers to the extent that something in you has been changed.