I first heard that Nick Waterlow was dead at 11 pm on the evening of 9 November 2009. I was about to go to bed when a person, who identified herself as Sydney Morning Herald journalist Geesche Jacobsen, phoned my mobile to ask what I knew about ‘‘the murder suicide’’ of Nick and his daughter Chloe. My furious denial of such a possibility only prompted more questions. The next morning’s paper had Jacobsen’s by-line, Nick’s photograph and two murders. No apology was ever made for that first allegation.

On reading Juliet Darling’s memoir of her life with Nick and her grief at his death, there is comfort in realising that the web of protection that was woven around her in the weeks after that terrible night worked. She was saved from the worst of the news media.

It is hard to write unflinchingly of the feelings surrounding the death of someone loved where there is a sense of the physicality of grief and a heightened awareness of the small details that amplify loss. The book that is closest to this memoir is C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed, written just after his wife died. The differences, however, are instructive. Lewis’ wife suffered a long painful illness. Nick and Chloe were killed by his son. While A Double Spring is part catharsis, it also encompasses a stark critique of the family dynamic that fostered internal jealousies.

Antony Waterlow’s condition was more complex than mental illness. Rachel Griffiths, one of the author’s close friends, claimed ‘‘Nick was killed by entitlement’’. The entitlement of wealth came from Nick’s first wife, Romy (called throughout the text his ‘‘former partner’’, not wife) who died the year before Nick met Juliet Darling. There was also the entitlement of birth through the Waterlow family’s descent from a baronet (Nick was himself heir presumptive to the title) which saw them embedded within the upper reaches of the English class system. The culture within the family was one where keeping up appearances was paramount. Juliet Darling comes from Australia’s own entitled class, but never have the gaps between British and Australian sensibilities seemed so wide. She cannot imagine the culture that sent the six-year-old Waterlow to a harsh boarding school, but she does see the resulting awkwardness between mother and son. ‘‘Every stitch on the needlepoint cushions has been threaded with resentment,’’ she writes before marvelling at Nick’s own emotional generosity.

‘‘trust, or the lack of it, was at the heart of this family’s problems. There had always been a lack of trust. No one trusted’’. There is a sense of betrayal as she realises, after his death, how effectively Nick Waterlow worked to hide the full extent of his knowledge of Antony’s mental deterioration.

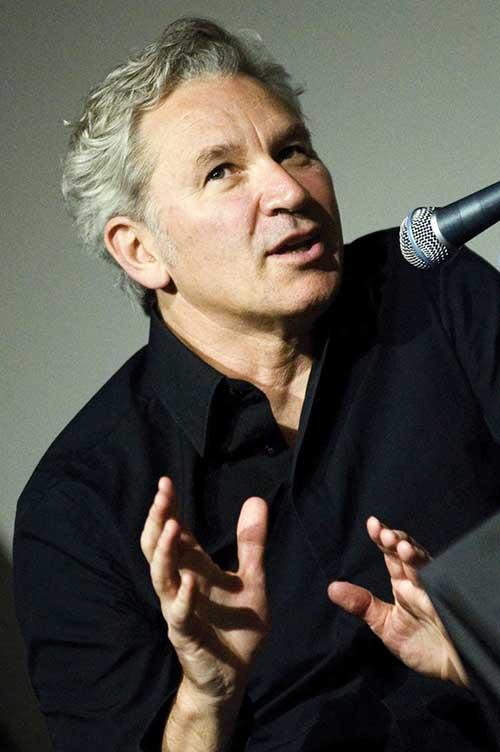

Darling is a fine writer and has chosen her words with care. This is her story about her grief. Names become important. Her friends are given full names when they are first introduced - so ‘‘Jane Campion’’, ‘‘Rachel Griffiths’’, ‘‘John Wolseley’’. Nick’s friends and colleagues either go by their given name (eg ‘‘Felicity’’ for Felicity Fenner) or by position. Ian Howard who took the burden of COFA’s grief upon himself is only called ‘‘the Dean’’. Yet they worked together for 20 years and Waterlow’s project for a modern gallery within a new art school was developed jointly with Howard. It seems ungracious not to name him.

Early in the book Darling describes the days after the deaths when ‘‘Time both sped up and slowed down’’. It slips effortlessly between descriptions of love and the aftermath of grief – the sadness of a solitary Paris spring which they had planned together, turn to sweet memories of an earlier visit. Sometimes the vignettes border on the bizarre. Nick’s ashes are divided among his family as though they somehow contain an essence of the man. Crass comments from a work colleague are countered by the empathy of homicide police.

The intensity of grief, combined with justifiable anger at the forces that led to these deaths make A Double Spring a compelling but not comfortable book to read. Resolution comes surprisingly when Darling sees the photographs of the murder scene with their evidence of the intensity of Antony’s frenzied attack. Nick Waterlow’s last words to his son were of love so that “even the worst can be endured and has been given to us for love”.