.jpg)

When I was an adolescent in the 1960s, gender defined/confined our lives. Young women especially lived with boundaries narrowed simply because of the nature of their genitalia, but the straitjackets affected all. Even at St George Girls High, a selective high school for the academically inclined, choices were narrowed when at the minimum school leaving age of 15, girls started to leave the classroom as they found unskilled office assistant jobs. Their families saw no point in educating them. Some girls simply vanished overnight when they became pregnant. People who did not fit the norm were not to be seen in public.

It is hard to describe the commonly accepted labour practices of the 1960s to the contemporary world. How to describe a world where air hostesses hid their engagement rings, because airlines sacked women who were engaged, and banks routinely dismissed a woman when they discovered she was married? Women's wages by law were significantly less than those of men, and one of the reasons that generation produced so many brilliant women teachers was that teaching was one of the few professions that paid equal pay for equal work – although men, naturally, took the top jobs.

Art schools were little different. In 1910 Julian Ashton appointed Mildred Lovett as his deputy at the Sydney Art School, but by the post-war years all official leadership positions, and most permanent teaching jobs, in art education were held by men. When Pamela Griffith was a high achieving art student at East Sydney Technical College in the 1960s, Douglas Dundas was quite open in describing the function of women art students as the future wives of artists and architects. The rhythms of Australian art reflect the rhythms of Australian life as a whole. In the late 19th century, when women were first allowed some form of tertiary education in this country, women students dominated art schools, and many exhibited. Some were even noticed, but not really by state institutions.

In the years between the two world wars many women exhibited and had significant careers. In retrospect (but not at the time) it is clear that the most interesting and innovative works of this time were made by women. After World War II when the country turned its passion to looking after the needs and interests of returned soldiers and their families, the presence of women artists shrank. In The Field exhibition of 1968 there were only three women represented: Normana Wright, Wendy Paramour and Janet Dawson. The 1973 Recent Australian Art exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales was even more strongly gender biased. Only one woman, Ewa Pachuka, who made knitted works, was exhibited.

Revolutions usually happen after times of great oppression, and the rise of feminism and the empowerment of women artists can certainly be seen in that context. But the changing perceptions of the place, intelligence, resilience and empowerment of women has also had consequences for the other gender – as well as people whose understanding of self either crosses genders or transforms them.

In the late 1960s, in working class Kingsgrove in the south-west of Sydney, St Thomas’ Anglican church was active in its youth fellowship. It was also at the heartland of fundamentalist evangelical Protestantism. In terms of visual imagery, the cross at the front of the congregation was replaced with a sandstone monument claiming: ‘‘Jesus said, if you love me keep my commandments’’ – which is probably one of the better examples of words taken out of context. In this unpromising context the rector was John Turner, a man whose lively intelligence and thoughtful responses made him especially attractive to adolescents looking for intellectual stimulus. When a young couple found themselves unexpectedly expecting a child, he did not banish them but comforted and counselled. Young men earnestly prayed that they not be led into similar temptation, but young women found themselves curiously irrelevant in these prayer circles.

John Turner was a single man. The Anglican Diocese of Sydney urged its clergy to marry, but he was an honest man who would not deceive a naïve young woman into a mariage blanc. Turner left St Thomas’ in about 1968 after a breakdown when he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital to ‘‘cure’’ homosexuality. He committed suicide soon after. In the following years some of the young men who had earnestly prayed not to be tempted by women’s rampant sexuality realised it was natural to enjoy the pleasures of their own gender.

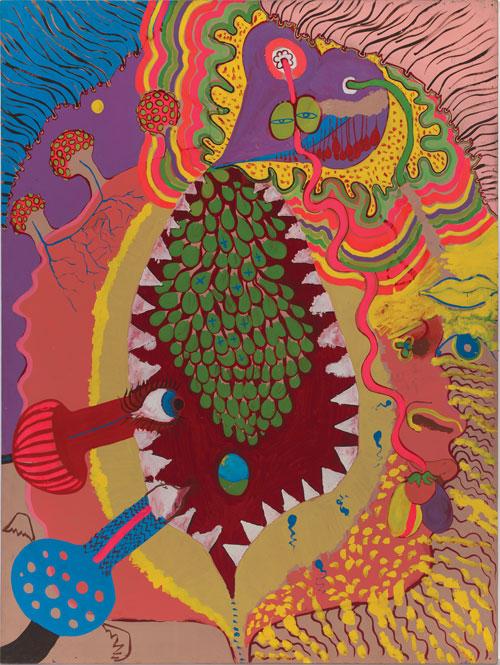

Away from the deadly suburbs the arts, both visual and performing, were already challenging the confines of gender stereotypes. In 1965 Frank Watters and Geoffrey Legge opened Watters Gallery which opened its doors to Richard and Pat Larter’s challenges to the nature of conjugal relations and bourgeois hypocrisy. Then, in 1967, Vivienne Binns’ first solo exhibition led to outrage among the male critics, who were used to being the only authorities on female sexuality. With the benefit of hindsight, Binns’ work can be seen as a part of the trajectory of Australian visual imagery connected with Mike Brown’s Mary Lou’s mockery of the airbrushed soft-core porn of Playboy and the satire of Oz Magazine. It fits neatly with the performances and installations at the Yellow House in the late 1960s and early 70s.

This is where the worlds of the creative underground, public performance and commercial enterprise begin to overlap. In 1969 the cast of Jim Sharman’s first Sydney production of Hair walked down the street to the Yellow House to see a genuine counter culture where the standard roles of male/female/straight/gay were under challenge in glorious technicolour. By 1974 Sharman had returned to Sydney with The Rocky Horror Show, starring Reg Livermore as the gender bending Frank ‘n’ Furter. Rocky Horror indicated a visual language that could be used to describe a world of dexterous ambiguity. It was echoed in the colourful Mardi Gras costumes and performances, and they in turn worked to encourage visual challenges on all fronts.

The times were indeed changing. In 1973 the arbitration court had finally awarded women equal pay for work of equal value (still providing a loophole to maximise disadvantage). Male homosexuality was to remain a crime until 1975 when South Australia recognised that the state did not belong in bedrooms and had no right to interfere with the lives of consenting adults. Fred Nile predicted this would start a national tsunami of permissiveness, while others hoped he was right.

The questions of the significance (or otherwise) of the sexual characteristics of physical bodies continues to intrigue artists, who continue to gently (or not so gently) mock those who wish to put everyone into neat gendered boxes.