.jpeg)

The big red book Dot Circle & Frame: The Making of Papunya Tula Art is the latest publication on a regional art movement that has transfixed and transformed Australian art and invigorated its art history. But do we really need another treatise on this well documented art revolution? This text argues the yes case with conviction: its originality lies in its corroborating the aesthetic achievements of its painter-protagonists through a close formal analysis of works created at a critical juncture in our country’s history.

John Kean is the assiduous researcher, interlocutor and archivist, but his ultimate co-authors are the men he identifies as the ‘gang of four’: Kaapa Tjampitjinpa (c1926–89), Johnny Warangula Tjupurrula (c1922–2001) and brothers Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri (c1930–84) and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (c1934–2002). In Kean’s storytelling, each performed a decisive role in Papunya paintings' emerging style, creating innovative works of intention in rigorous dialogue with one another. The fifth protagonist is the historical first: Albert Namatjira (1902–59), whose syncretic visual expression founded the Hermannsburg School (1936–1948), its legacy which Kean refers to as the watercolour painting movement (1950–).

It’s not uncommon today in curatorial and educational contexts to cite Namatjira as the inaugural professional Aboriginal artist, and thus the originator of the contemporary Indigenous art movement, by way of example initiating ‘dot painting’ at Papunya. At first take, Dot Circle & Frame’s two-part structure reflects this. In providing a detailed and convincing exposition of both period styles and their preceding histories, Kean perforates the borders between two (apparently) vastly different modes of representing cosmologies and ‘lifeways.’ [1] As the book’s title indicates, the signs, figures and icons employed to translate environmental and ritual knowledge into a rectangular ‘picture’ for universal audiences are the deeper incentives at work—from the semantics and politics of the dot, to the conceptual liaisons between watercolour and ochre, body, ground and earth.

The author had an active hand in the early years of Papunya Tula art: in his opening lines, Kean locates himself at Papunya in May 1977 and describes his schematic drawings of 'several hundred paintings’, learning ‘to appreciate the semantics of the painting’s construction’ and ‘the hand of each of the thirty artists who had created the works’. This acquired skill of deep observation, coupled with his curiosity about the paintings ‘makings’—he was fresh out of art school—drives the narrative forward and informs the deep investigations of individual works, their material conditions and metaphysical and communicative powers. Over the decades since his role as art advisor with Papunya Tula Artists co-operative (1977–1979), Kean has kept close professional and personal relationships with the artists and their extended families and descendants, such that a book like this has been possible. As Stan Grant said recently, the question to ask is ‘not who you are (this will get you killed in many places, even today), but where you are.'[2] It’s a call—and a responsibility—that Kean takes in all seriousness, and refreshingly without earnestness.

Dot Circle & Frame is a reader-friendly book with a double-pitch that serves the new or established scholar of desert painting. Kean sets out his thesis in a brief introduction of method, chronology and nomenclature, addressing some common misconceptions. (If you ask OpenAI’s ChatGPT about the origins of contemporary Aboriginal art, Geoff Bardon’s name will surface as the catalyst of Papunya painting in 1971). It’s Bardon’s self-referential writing, specifically Aboriginal art of the Western Desert (1979), that Kean re-sites in his argument as an art movement from Central Australia, in which ‘…Papunya painting can be viewed as just one facet in a kaleidoscope of transactional dynamics spanning the region’. Still, Kean draws heavily on (and revises some of) Bardon’s detailed records and engages with the important research of Vivien Johnson who first declared ‘The School of Kaapa’ in 2010.

In the cross-cultural domain of Dot Circle & Frame, Kean’s usage of ‘transcultural’ applies to the impact of introduced materials such as comics, cameras and cowboy-culture, whereas the ‘intercultural’ implies the ‘social and intellectual interactions’ between different Aboriginal cultural blocs and outsiders (from preachers and pastoralists to anthropologists and art advisors). It also refers explicitly to the interrelated ‘triangle’ of Anmatyerr, Arrernte and Pintupi (‘Western Desert’) people who collectively brought forth Papunya painting—a phenomenon in which art world interest, research and markets have privileged the latter.

In Central Australia, the transcultural has other implications, in which the colonial imports of bibles and guns reached a crisis point in 1928, a year Kean treats accordingly as a double cataclysm. The Coniston Massacres (where an estimated 140 Aboriginal people were killed near present-day Yuendumu) forced survivors into refuge on missions or cattle stations;[3] months earlier at Hermannsburg (Ntaria), Lutheran missionaries removed secret/sacred objects from their stony reliquary on Country, revealing them to the uninitiated congregation (i.e., women, children and outsiders) in an ‘iconoclastic test of faith’ between the Tywerrenge and the Cross. A letter from Hubert Pareroultja to the author in 2021 expresses the intergenerational pain of this event, and points to the immeasurable cost of colonialism and the high stakes of cross-cultural projects. It also highlights the importance of Kean’s documenting activities at Winparrku, west of Haasts Bluff (Ikuntji), in which Tjartiwanpa reconciliatory ceremonies have traditionally been performed to mediate conflicts–long before colonial invasions occurred, and well into the 1970s.

A bipartisan philosophy drives Kean’s enquiries, and he seeks the intercultural without revoking the artists’ agency or assuming advanced authority. Given the scarcity of fluent desert language among art advisors, and the absence of written accounts directly by the artists, the paintings remain the primary source material. In an unlikely turn but in accord with the transcultural theme that underpins his argument, Kean draws on his education in Western modernism throughout; one example is using American curator William Rubin’s account of Braque and Picasso’s collaborations (i.e., the invention of Cubism) as a model in his formal assessment of collaborations between Possum and Leura. Such equivalence in the intellectual innovations of modernism’s avant-garde and ‘[the Tjapaltjarri brothers] exceptional grasp of pictorial space’ might offend some readers (after all, Rubin’s controversial 1984 exhibition, Primitivism[4] has become a metonym for failures in the cross-cultural field)— but Kean’s approach underscores the primacy of the artworks’ materiality, so successfully turned to transcendental ends by his subjects: ‘…[Leura’s] ‘paintings derived frisson from the dialectical interplay between the symmetry of religious iconography and the liminal properties of diluted paint…’

Courtesy D’lan Contemporary

Kean pushes against the tendency to essentialise Papunya painting (and by extension art from remote communities) and to place interpretation beyond comprehension as ‘enigmatic’ and untranslatable—while acknowledging there are aspects of these paintings to which he has no access (isn’t this true of all art?). Beyond the paintings and the artists, Kean draws his ideas from anthropology, art and social histories, linguistics and curatorial studies; whether speculating on Namatjira’s experiments with photography as a compositional device, or the influence of comic books as a narrative structure in relating Dreaming stories, he demonstrates that an appetite for exchange runs both ways.

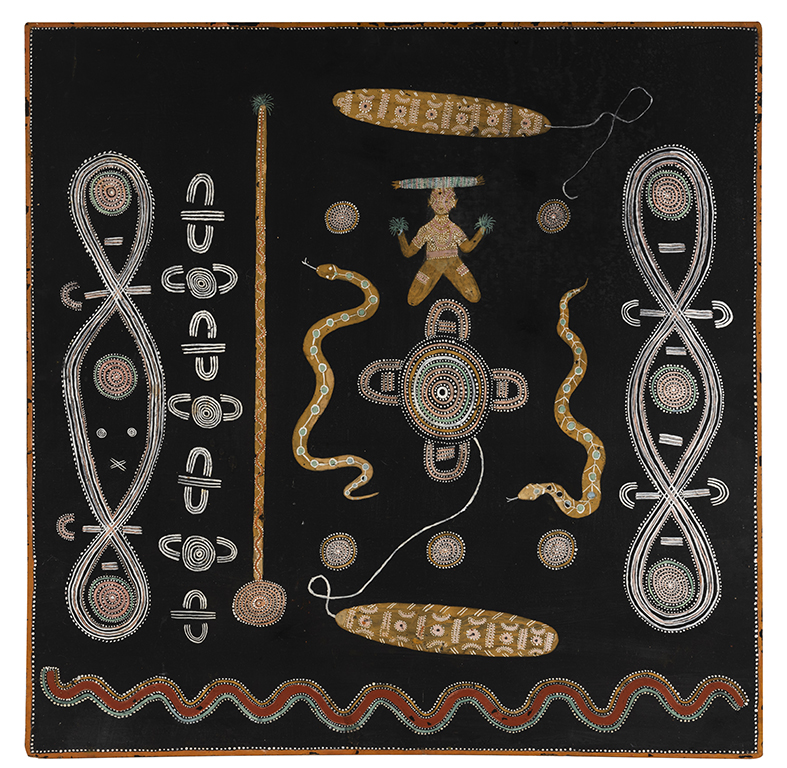

The book’s two parts are separated by 70 pages of colour plates on matte black pages. These design choices mute the reproductions of dazzling works in this richly illustrated large format soft-cover book. As an editor, I appreciate the obdurate character of typographical errors and there are a few worth noting: the nineteenth century natural history illustrators, the sisters Helena and Harriet Scott, were active on Ash Island, which is situated on the Hunter, not the Hawkesbury River. Elsewhere there are some errant captions and plate references, and Ngitjita Willy Tjungerrayi’s The Kuniya Kutjarra (Carpet Snake Two) at Patjantja (1973) is dated in error, as large-scale canvases were not stretched at Papunya until 1974. If this seems pedantic (and it may be a flaw already logged in the archive), its emblematic of the systematic revisions that Kean has troubled over and which constitute the book’s fine-grained offerings, including its useful appendices.

As Dot Circle & Frame was being prepared for print, a board from Kaapa’s first consignment of paintings to Alice Springs came to light after fifty years hanging in a private home in Adelaide. For posterity, and as if a covenant with the Papunya artists—to whom the book is dedicated—Mikantji and Tywerl (1971) offers a conclusive coda. Ushering in a new pictorial space between perspectival landscape, biography and cultural knowledge, it reinforces Kaapa’s indisputable ‘agency as broker of cultural exchange’. This seminal work—likely made on a blackboard possibly reclaimed from the school—was recently exhibited in Melbourne with an asking price of half-a-million dollars, small change for a ground-breaking painting that helped inaugurate a movement widely framed as Australia’s only art revolution. It’s the nuanced origins and continuities of this ‘revolution’ that this book so clearly signals.

Footnotes

- ^ Lifeways is a term Kean has employed within, possibly in rejection of the ‘lifestyle choice’ condemnation made by former Liberal Prime Minister Tony Abbott in 2015 as his government planned to cut support for 150 remote communities in Western Australia.

- ^ Stan Grant on truth-telling and the role of the media, in conversation with Scott Stephens, ABC Radio National 17 June 2023.

- ^ This figure is drawn from four related massacres around Coniston between August and October 1928. See Lyndall Ryan et al: Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788–1930, The Centre for 21st Century Humanities, The University of Newcastle

- ^ William Rubin, “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 27 September 1984 –15 January 1985.