‘The Black Eureka’ or ‘How the West was Won’ are some of the titles and slogans by which the Pilbara Strike (1946-49)—in which about 800 Aboriginal indentured workers walked off some of the Pilbara’s largest pastoral stations—would come to be known. Like the Gurindji Strike or ‘Wave Hill Walk-off’ (1966-72) in the Northern Territory, the Pilbara Strike continues to be taught and talked about across the country, and sometimes the globe. The exhibition at John Curtin Gallery examines a group of strikers and their descendants known as ‘The Strike Mob’, and later as ‘The Strelley Mob’, who formed a new community with the purchase of Strelley Station in 1971, continuing the movement of resistance, self-sufficiency and cultural business.

The Strelley story is the historical backbone of the show, which spirals both backwards and forwards. It captures the establishment of a community school and literature centre at Strelley that published its own books in Nyangumarta, many of which would be read aloud to the community. The show also cites a third era—the present-one—that re-engages with the expansive Strelley archive and its unique art and literature, much of which is being seen outside of its original context for the first time and includes new animations made from a selection of the books. While production at Strelley was largely turned inwards to the needs of the community, the exhibition positions both the strike and Strelley as contexts crossed by networks of outside connection—political, artistic and cross-community solidarities emerge. These connections are interlaced with stories, images, and animations that take us into the expanses of the Nyangumarta universe and cosmology.

The three overlapping historical touchpoints of the show–the Strike era, the Strelley era and the present-day–provide vantages onto one another, teaching us the history, how it was taught, and suggesting how we might learn and re-learn from it. The exhibition also centres storytellers and artists—strange pedagogists and historians that they can be—and how they do their cultural work in visionary ways. Co-curated by art historian Darren Jorgensen, Sharon Hale and Barbara Hale (curators, language holders and daughters of Monty Minyjun Hale–the principal linguist at the literature centre), the show emphasises how this was an art and literature movement of and for Nyangumarta, Strelley and the Pilbara—but one that has a lot to say to outsiders too.

In the first gallery we see works by non-Indigenous artist comrades who were involved at strike camps or Strelley Station (Allan Baker, Sam Fullbrook and James Wigley); vitrines with unfolded sets of delicately illustrated Strelley school books; a contemporary painting by Rose Murray, Our families gathered pearl shell (2012); and a single, but potent, historical object—a tin yandy by Spearim Jimmy collected in 1940, used to sift and shake minerals from sand. As a kid, I remember being told about relatives who had been yandying down at the Yule River and imagining the glimmers in sand and water, not grasping then just how revolutionary the gesture was.

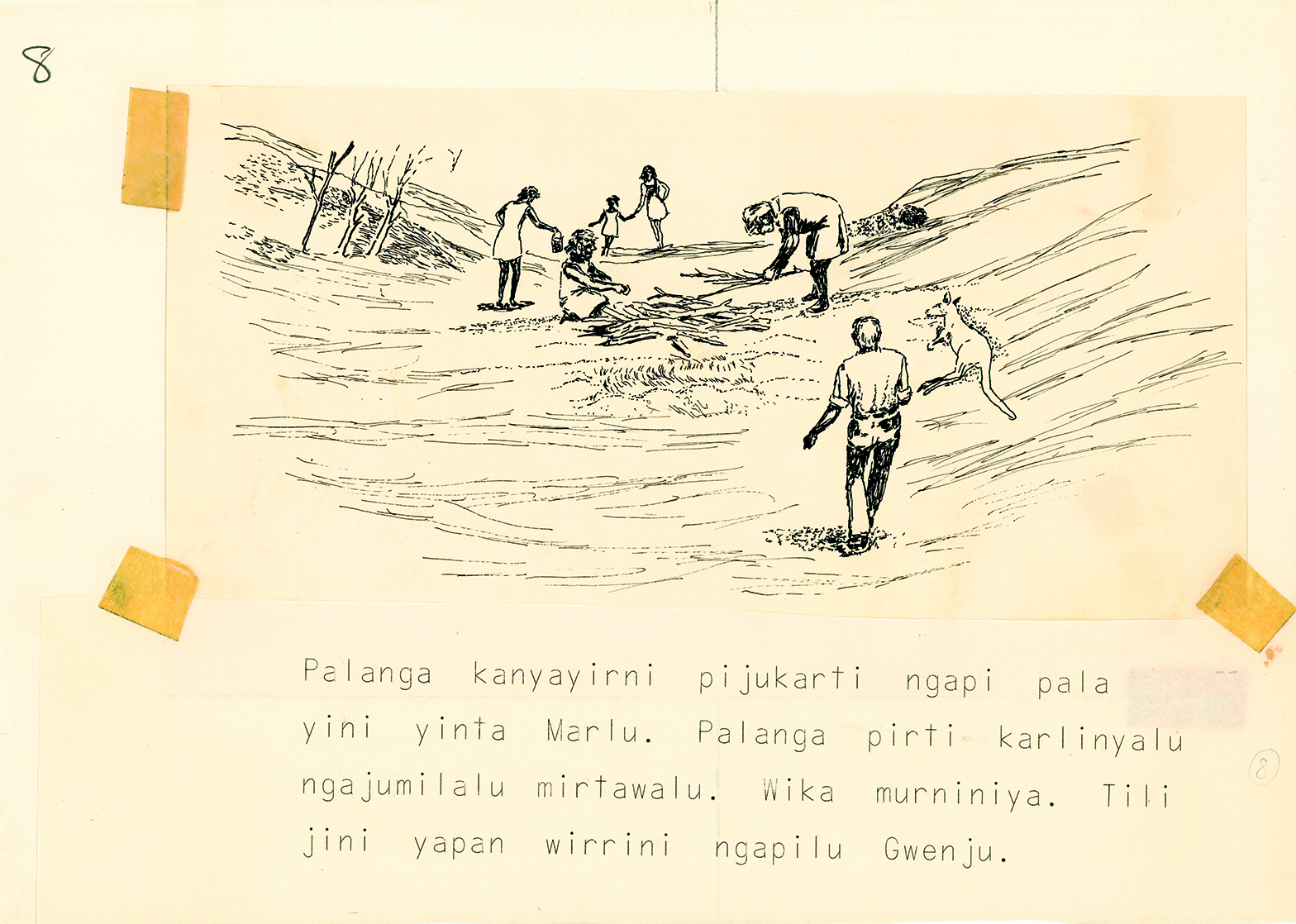

What is hopefully the first of many public outcomes for this major research project, the exhibition is a complex but selective offering from the expansive Strelley archive. While there are key access points into the story—provided through short, plain English texts, an animated map by Annie Huang and the openness of the objects themselves—the criss-crossing density of the histories here can take some sinking into. But this tracks nicely alongside the pedagogies and methods at the heart of Strelley—schoolbooks written in Nyangumarta do their language teaching and story sharing. Marrngupa Kamal [The man and the camel. A story about a cold camel] (1980), by Fred Rurla Bradman, shows a chilly camel displacing a man from his tent and needs little explanation. There is a wonderful selection of early drawings by Nyaparu (William) Gardiner, one of the only artists to attract later artworld renown. Gardiner made the first illustrated story for Strelley, which has been transformed into a new animation, Japartulupa pipilu ngaju kanyanyipulu kuyikarti / [My dad and mum took me hunting] (2024) directed by Vladimir Todorović, with storytelling by Sharon Hale and animation by Jullie Ziegenhardt.

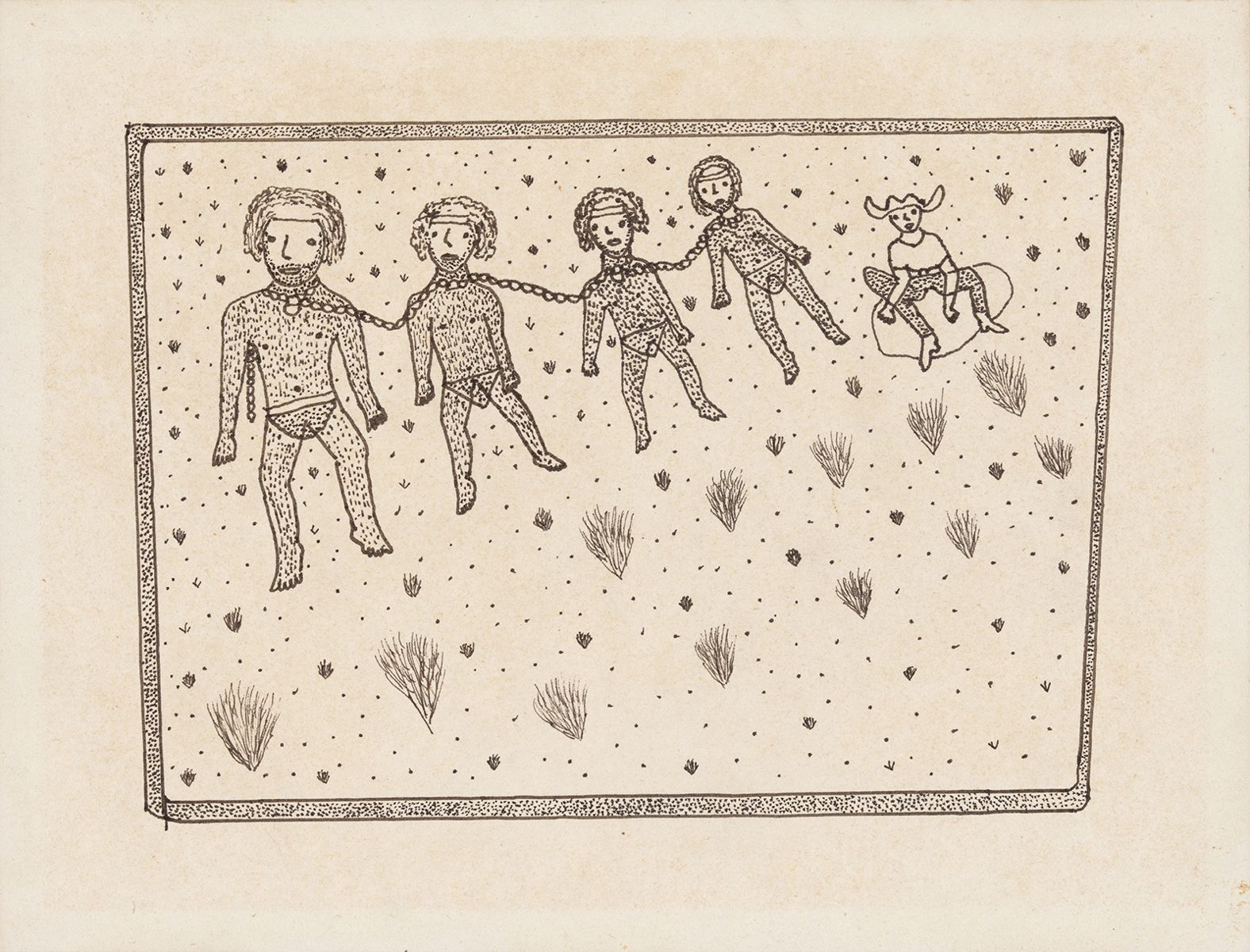

Forming a threshold between the first gallery and a more immersive setting for video installations is a corridor of vitrines containing drawings by Solomon Cocky Ngalyarrkiny, pulled from a cache of some 300 illustrated books made between 1979-1991. As Inge Kral and Darren Jorgensen suggest, the works readily eclipse the most expedient registers for language teaching and become part of a much wider and experimental practice for passing on knowledge.[1] The images show lively creation stories drawn from Ngalyarrkiny’s vast custodial responsibilities, finely detailed bush tucker and single frame compressed narratives from colonial histories of the region–from the 1905 Braeside Massacre to a story about police shooting dogs at a strikers camp to a line of chained strikers subjugated by a crouching policeman.

Photographs of neck chaining have become a visual synecdoche for the violent colonialisation of the northwest of Western Australia and sometimes for the nation, often with limited context. It is both humanising and incisive when encountering these deep and brutally violent histories through the careful holding of these stories from within and made for the community. Cocky’s jaunty figures and animals, delicately rendered in fine liner pen with short, dashed strokes, draw upon a deep well of cultural, historical, political and social knowledge held by the artist, all within the same comic book style frames.

While the first two-thirds of the show immerses us in a dense constellation of artworks from the archives, the final theatrical chapter sinks deeper into four of its stories, newly animated in digital form by director Vladimir Todorović, and his team of collaborators, and told in Nyangumarta. Timed and paced to move viewers through the space, two of the stories (derived from books) enliven Nyangumarta Dreaming narratives: Murtilyalujirri Nyungurrangu Yarnimarnapulujaninyi Paaikatapa Wirlarra, Yirntirri [These two Murtilya boys made the stars, the moon and the Milky Way] and Warla yirrirni pirirrilu [The man saw the lake], both 2024. These are narratives that were already experimentally mediated into a new kind of storytelling through book production at Strelley. The animations remain sensitively close to the material form of these stories–drawings, archives and voicing–working with the lively ‘animated’ movements suggested within these forms.

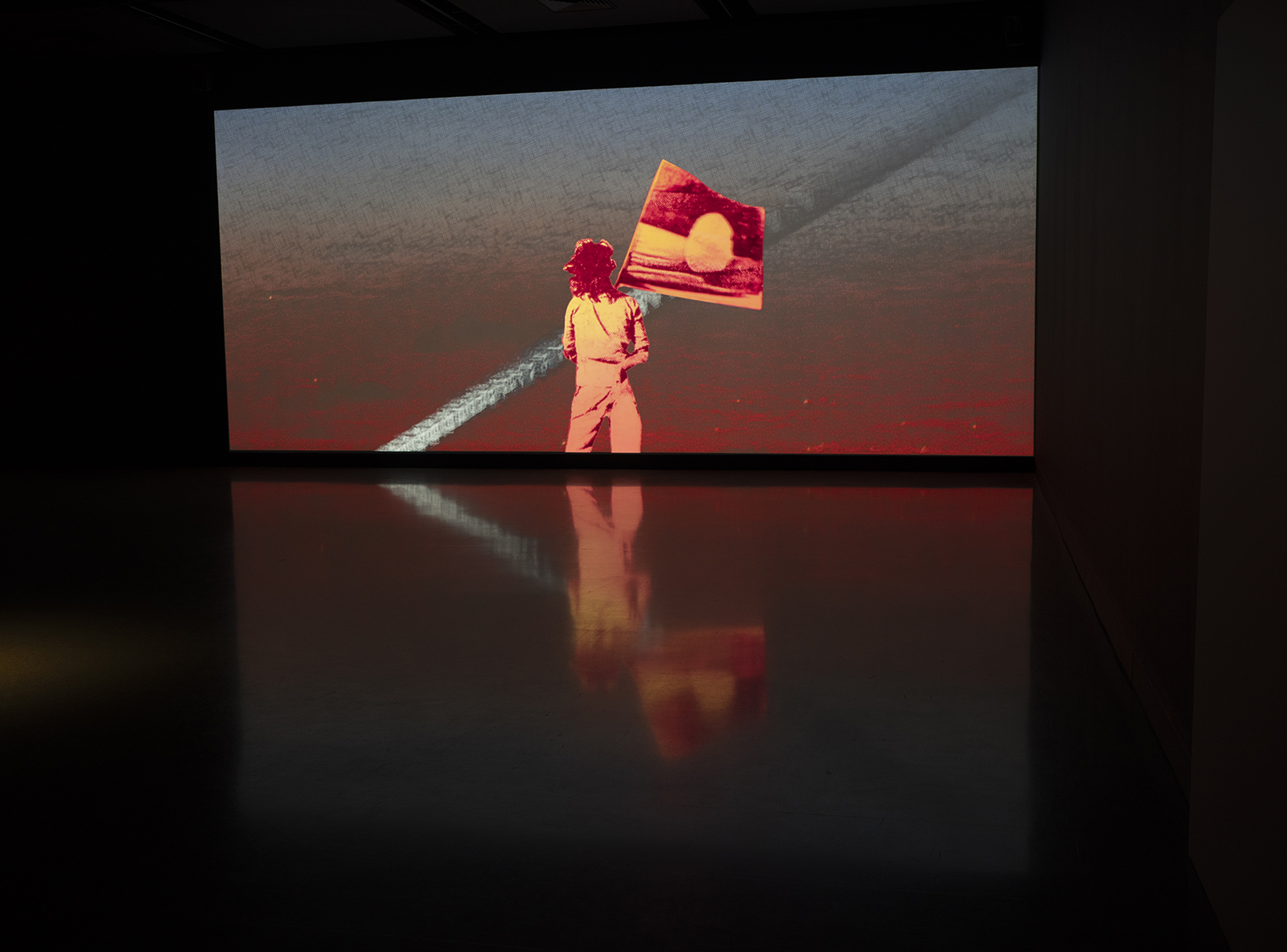

Another animation, The Convoy (2024), works from photographs and narrates a chapter in the story of the 1979-80 Noonkanbah Protest in the Kimberley—another major industrial action led by Aboriginal workers at Noonkanbah Pastoral Station to resist oil drilling. It covers the day when a fleet of 33 trucks transporting a drilling rig, accompanied by a large police escort, were confronted on the bridge at Tabba Tabba Crossing by mob from Strelley. We see police physically move the demonstrators on, and the long line of trucks snaking across the land. We read the powerful conclusion of the episode in typewriter text on the red of the manila folders from the archive: ‘The convoy thundered past as people begin to sing.’ It’s a poignant, sad and strong moment of solidarity across the cultural and political ties that bind these communities and regions, and the histories of people who have resisted the powerful nexus of government control, policing, pastoralism and mining.

Strelley Mob sits beautifully in dialogue with the gallery’s concurrent exhibition, N'yettin-ngal Wagur – Yeye Wongie [Ancestors breath – Today talk], curated by Zali Morgan (Whadjuk, Balladong and Wilman peoples). It brings together responsive works by four Noongar artists–Amanda Bell, Brett Nannup, Lea Taylor and Tyrown Waigana–in response to John Curtin Gallery’s major collection of works by the child artists of Carrolup (The Herbert Mayer Collection of Carrolup Artwork). Together, the two exhibitions display potent, culturally embedded responses to expansive archives—primarily of drawings—and find poetic ways to accrete the many relationships across people and time to continue the teaching and telling of these stories. Rather than an archival poetics that primarily confronts colonial archival logics, these continuances work from the artistic and pedagogical experiments and resistances of the past, centring uniquely Noongar and Nyangumarta epistemologies.

Footnotes

- ^ Inge Kral & Darren Jorgensen ‘The illustrated literature of Solomon Cocky: turning the Dreaming into books’, World Art, 14:1, (2024): 28.

_Card.jpg)