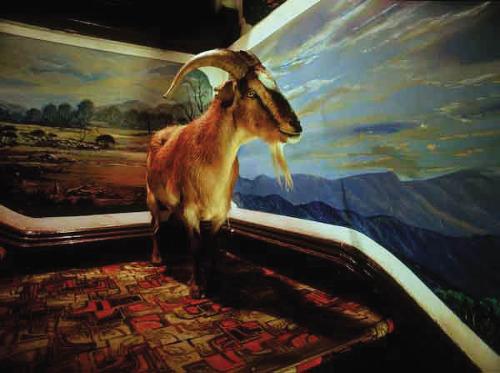

This book is a fitting companion to a splendid exhibition celebrating Japanese art collecting in Australia, in particular the Art Gallery of South Australia, exploring the origins of its Japanese collection, and revealing Adelaide's 19th century collecting attitudes. The 'Golden Journey’ is a reciprocal one between east and west, the adaptive interplay between Japanese art production and Western collection. The book shows how export ware combined Japanese craftsmanship with Western requirements, even before the Meiji era fostered specific examples like the florid yet exquisitely made Shibayama Cabinet. It roams through Japanese history, from a 6th c. Haniwa dog to Toshikatsu Endo’s mystical canoe Allegory 111, contextually odd, the jump from the Meiji period to 1988 points up the lack of continuity common to Australian collections.

Reflecting its rationale, the slightly random nature of the show is more evident in a text. The first section, Buddhist and Shinto art, is prefaced by a comparison of the golden Amida Nyorai with the fierce Zaô Gongen, which, although both from the Edo period, introduces the historical complexities of Japanese Buddhism, in which Buddhist and Shinto ideas were entwined in complex religious forms. It conjures up the late Heian period and contemporary fears of mappô, a dark age of chaos and confusion, which made popular the simplicity of Amidism offering salvation through simple concentration on Buddha’s name. The experience of the dying devotee is beautifully realised in a 14th century hanging scroll, Descent of the Amida Trinity.

In later sections - screens and scroll paintings, woodblock prints and decorative arts – the diversity of treasures is a delight. Disjunctive interconnections tantalise, as one flits from a Shigaraki teabowl to dramatic dragons in the Priest’s Mantle, patchworked for a ‘cast off’ quality.

The Genji and Heike screens plunge us again into the Heian era, from courtly pursuits to the Minamoto/Taira battles, the latter a handsome foldout, as is Arrival of the Black Ship, c.1590, depicting a Portuguese trade ship. The Momoyama period of continual conflict and high art is also represented by a magnificent chest displaying Portuguese influence. Despite the banning of Christianity in 1614, Tokugawa policies first encouraged trade, but the 1830s Exclusion decrees expelled the Portuguese and forbade Japanese travel abroad. Tightly controlled Dutch trade continued, even with annual court embassies.[1]

Woodblock prints contrast the settled serenity of Harunobu’s beauties to the eloquent drama of actors and heroes, some hinting subversion, like Kuniyoshi’s later prints criticising the declining Tokugawa regime.

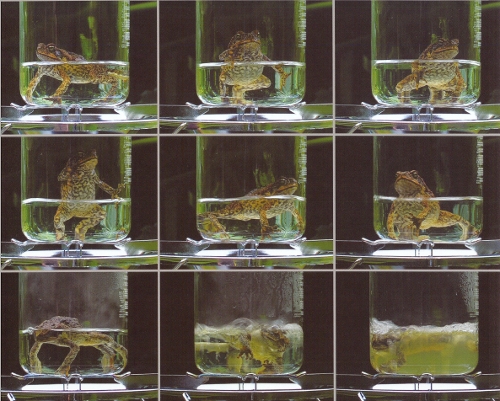

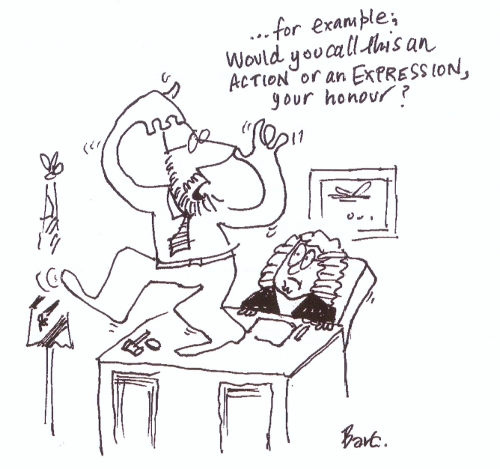

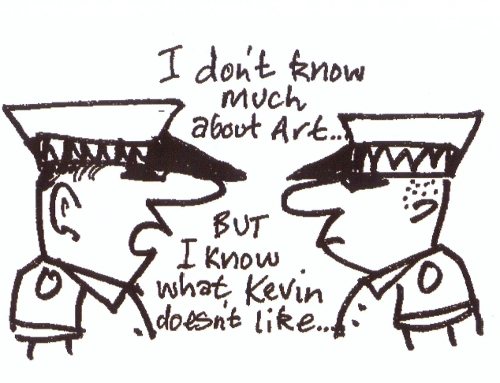

The essay on landscape prints analyses the opposing Japanese and Western ways of conveying space and the resolution seen in Hokusai’s masterly integration of perspective. A final tidbit: Kyôsai's unusual self-illustrated biography (1887). A Kano school painter of independent spirit, he recorded his life and traditional techniques to encourage their modern use, lest they be lost. Photography made this obsession obsolete; more interesting now are his delightful career episodes, from childhood in Kuniyoshi's studio aswarm with disporting cats to his spontaneous public displays, once doing 118 paintings in 8 hours, which might stand today as performance art.

Footnotes

- ^ Sansom, G, History of Japan, vol.3, p135 and 188, Tuttle, 1974.