When it was announced that an indigenous art prize, "Australia's richest", would be developed in Perth, I had hopes that the Award was going to be a recognition of the immense talent of Western Australian indigenous artists and would serve to familiarise Perth audiences with them, artists from our own region who have stellar careers, some of international significance, but who are rarely exposed to the general public. Problems with state borders and boundaries would have been tricky but instead, this opportunity became a national show of indigenous art. The result is a strong and compelling field of dazzling works from around the country yet I can’t help feeling that the Art Gallery of WA and the Government of WA, who have provided the funds, have missed the chance to celebrate their own (neglected) backyard in favour of a national prize.

Despite my reservations, this exhibition is one that you can immerse yourself in for hours, and especially so because each artist is represented by a small body of work. There is a wonderful feeling of moving around the country, from city to dry lake, from shopping centre to dreamtime.

The photographic series Optimism by Tony Albert of Queensland depicts a young man from behind, modelling a traditional woven basket (jawun) unique to his country, in a series of environments both urban and rural. These images bring the past and the present into dialogue as well as creating a tension between artefact and utilitarian object. As in most successful artworks, both the surface and subject seduce, leading us to ponder the infinity of political messages relevant to indigenous art that revolve around fashion, commodification and cultural practice.

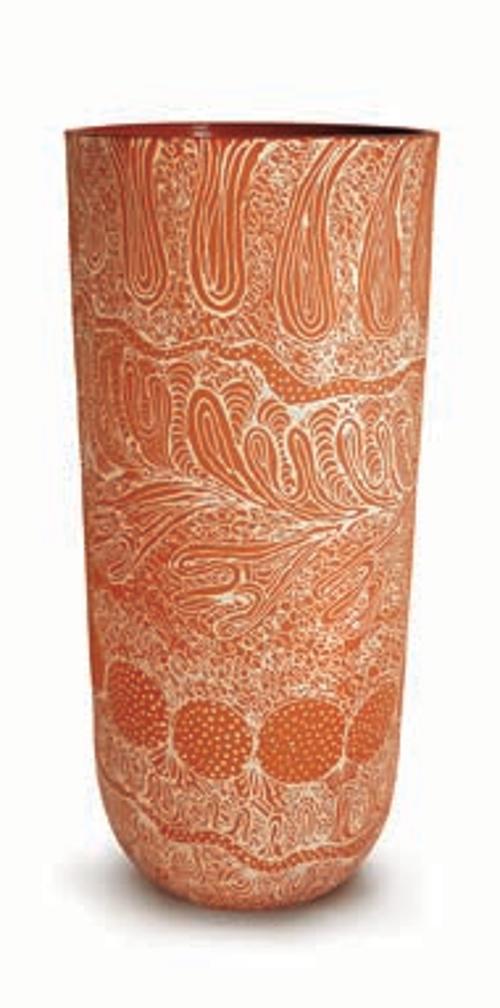

The notion of the artefact as work of art plays a big role in the exhibition. Yolgnu artist Gali Yalkarriwuy Gurruwiwi danced at the launch, as well as showing his Banumbirr - Morning Star Poles decorated with earth pigment, bush string, human bone, hair and feathers representing the Morning Star or Venus. The powerful ceremonial objects of Ricardo Idagi from the Torres Strait Islands were awarded the $50,000 first prize. These headdresses and masks are created using traditional tools and materials such as turtle and other shell, feathers, seeds, hair, cane, raffia, nuts and ochre. They are a celebration of the living culture of the Torres Strait Islands, and the fusion of its religion, law and art. Fellow TSI artist Dennis Nona has similar concerns, mining his traditional stories to keep them alive for the generations to come. Nona transfers his carving skills into the medium of printmaking as well as sculpture. His skull Byerb Ibaik, cast in brass, with pearl shell and seeds, is a very accomplished and contemporary piece of work that engages the viewer even if they are unaware that skulls were a significant form of currency, as well as ceremonial objects in TSI history.

Painting is central, and just as vibrant as could be expected. The vibrating optical paintings of Doreen Reid Nakamarra bring the Kiwirrkura sandhills into three dimensions and some mystical land magic (or paint magic) allows us to walk those hills. Her minimalist zigzag repetitions capture both the shimmering heat and the undulations of her part of the Western Desert landscape.

Walmajarri artist Wakartu Cory Surprise, living in Fitzroy Crossing, won The Western Australian Artist Award of $10,000. She is an artist who has painted the same story/place over and over, confidently distilling the elements and exploding the colours of her childhood water sources in the Great Sandy Desert.

A High Commendation was given to Perth-based Chris Pease whose paintings deal with Nyoongar heritage and identity. Pease’s work combines postcolonial concepts with painterly appeal. In Law of Refraction, Pease reworks a rather creepy drawing (or caricature) of an Aboriginal group encountered by the artist Louis de Sainson, who visited King George Sound in 1826. One of the Minang men has been dressed in European garb and is showing his mirror to the others. Upon this image Pease superimposes a drawing illustrating the physics of light as well as a grid of symbolic roundels, juxtaposing the old and new worlds in a collision that continues today in Australia. Nearby, a minimalist panel employs as paint, balga resin from the native Xanthorrhoea once commonly referred to as blackboy. I dive into the sticky treacle of its reflective surface contemplating all and nothing.