By the ancient pond

a frog leaps

the sound of water

Matsuo Bash's famous 'frog haiku’, c.1686.

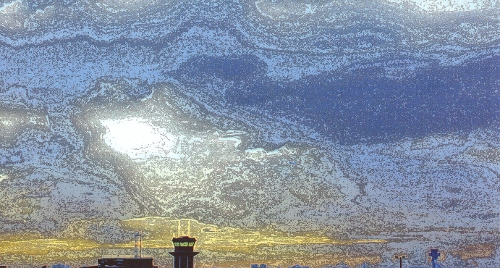

Tim Burns manages to paint landscapes that appear almost abstracted from the real world, while at the same time emitting a fullness of personal experience and intimate knowledge. His large, physically heavy paintings have long hummed with passion; they refuse to be locked into a state of coldness or be separated from their very real emotional content. Standing before a Tim Burns work has often meant becoming engaged with a relationship where you are pulled in and pushed away from the canvas in a cycle of mesmerizing contrasts: light and shade, physicality and ethereality, stillness and movement; presence and absence. The exquisite beauty of so many of his large landscapes seems to emerge from this duality. Burns uses contrast to awaken our senses, to highlight the beauty of life and of the natural world around us. It is an aesthetic construction that finds a natural affinity in Japan.

In From the Garden four large works Water Garden, Moss Garden, Sand Garden and Shadow Garden (all 2009) were painted soon after Burns’ recent stay in Japan. These paintings are a leap of faith from an artist well-known and collected for his very recognisable imagery; this stunning preview into Burns’ new world offers up a deep and sensual glow.

The paintings slip between being depictions of interiors and exteriors. At one moment they are erotic images of Japanese water gardens - still, lush, absorbent and reflective of all in the atmosphere around. The next moment, they lie like lush Turkish carpets strewn around the walls of an old covered bazaar, hung to smother the noise of hagglers escaping the desert sun. They fuse into fragments of images of Indian gods, lit by temple candles, before dissolving into sultry memories of late-Victorian drawing rooms, filled with souvenirs from the mysterious Orient and grand trips "abroad". They allude to the stillness of a Zen garden and appear profoundly serene. They exude the familiarity of domestic interiors, contrasting with the glorious cacophony of birdlife and flowers. Finally, they become landscapes again and freedom and light scatters all. The air is heady with perfume. Everything is alive.

In Moss Garden Burns politely borders off this world at its front; neat garden tiles keep the garden beds or pools of shadowed islands in check as they float across the painting’s surface. Moored by the introduction of perspective, the segmented spaces are kept lightly in the image. A bejeweled flower lies beyond a waterfall at the end of the central garden path, which seems also a river or a pond. There is a field of flowers, painted in hothouse colours like pink, mauve, cerise and yellow, and there are references to Burns’ more familiar imagery floating beneath the surface. Land and water are transformed into each other; modified by each other; become one another. A bird sits within and apart from the scene. It appears well-pleased.

Shadow Garden seems as intimate and well-worn as an ornate Edwardian dressing-gown, yet is as publicly large and familiar as a Monet or Whistler from the same era. What I love so much about this painting is Burns’s disregard for what his painting “should” be. This painting is enormously generous in its offer of the permission to be free. It is dense, opulent, sensual, almost hilarious in its raw colours and sheer delight. It is full of a life freed from physical limitations and connection to place.

While his work has remained so closely linked to his relationship with particular landscapes, Burns has always managed to achieve a sense of freedom from the material history of our lives as they are fixed in place and time. Transforming his vision of specific, intimately known landscapes into fields of pure sensation, Burns has always had the capacity to remove these places from the real world. Following the painter into his vision as we enter the painting, to float through a Burns landscape is like an out-of-body experience that refreshes and heals on so many levels.

Strangely, it seems to me, Burns’ paintings possess so much that digital art promises – freedom from our physical selves, the capacity to lose our “feet of clay”. But these paintings are made with, and contain, a very un-digital human touch. They pulsate with thick paint and lush colour, with a sense of tradition and history, which is not hidden or denied but forms a foundation from which new ground can be forged.