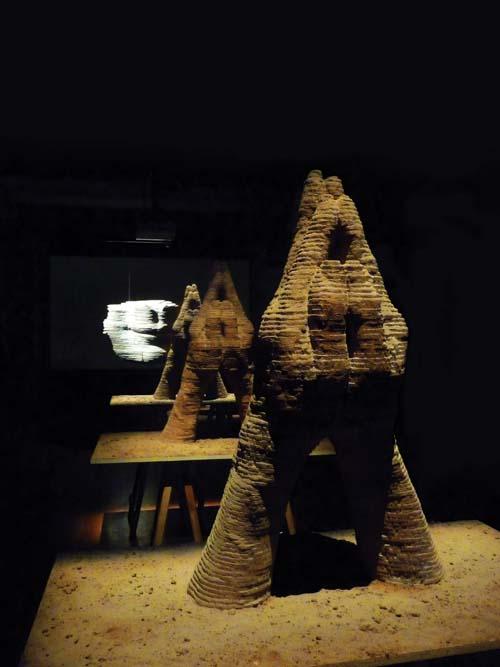

In Anne Ferran's 'The Ground, The Air', an exhibition of photographic séance, a mesmerising collection of 30 digital prints on aluminium entitled 'Lost To Worlds', depicts the former women’s prison in Ross, Tasmania. Active from 1847 to 1854 and known as a 'female factory’, it is a far from a picturesque ruin overgrown with ivy. All that remains of the prison are the few broken bricks that scar the countryside.

Peering from the gallery’s mezzanine level is another series, Ferran’s 1995 'Soft Caps', which depicts the caps worn by women in Sydney’s Hyde Park Barracks. Floating above the main gallery space, this work bears silent witness to one of Australia’s difficult histories that remains buried in the most literal sense.

Altogether, 'The Ground, The Air' is a sombre and well-realised reflection on Australia’s brutal colonial past. The simplicity of the exhibition design belies its effectiveness as the lack of technical gimmickry or didactic text panels amplifies its sinister ambiguity. Darkened slightly, the bureaucratic tinge of Wollongong’s gallery space perfectly echoes the narratives of institutional cruelty peculiar to Ferran’s photographs. The placement of 'The Ground, The Air' to suit the Wollongong Art Gallery is both confident and precise, recognising the need for both subtlety and restraint.

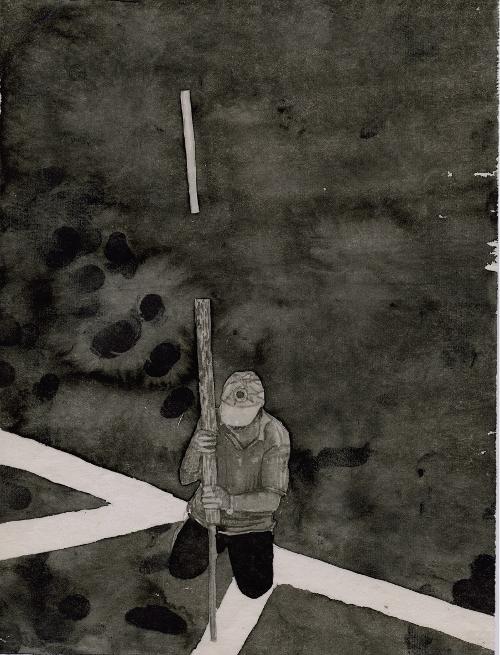

Ann Ferran’s 'Lost To Worlds' series of digital images is both evocative and technically satisfying. The artist’s lean, descriptive prints on aluminium drift between the forensic and the speculative. Simultaneously documentary and abstract, the formal grace of these images could be mistaken for accidental. The panoramic sweep of the lens seems desperately intent on conjuring colonial spectres or skeletal traces. Yet the ghosts of Australia’s violent past do their best to escape Ferran’s inquiries.

Surely a site of immeasurable cruelties, visualising the trauma buried alongside the Ross women’s prison is a deed of immense difficulty. Ferran identifies the tangible quality of absence in her aching images of scruffy paddocks and rugged hills. The sparseness of her imagery speaks of the desertion found only in places that are ‘haunted’. Dogged by a dark past, such sites are either enshrined as memorials or covered up with earth.

Yet within 'Lost To Worlds', the camera becomes a mysterious X-ray, exposing murky figures hidden amongst stern countryside. An analogue for the human body, the looming shadows of the landscape emerge as dark bruises, tussocky shoulderblades and grassy silhouettes. Ferran’s grasslands are an estranged, hallucinatory terrain whose biting monochrome renders the scenic isolation of the site disturbing. Suspiciously mute, the earth itself seems to conspire against the viewer, secretly swelling and shifting when out of sight. 'Lost To Worlds’ depiction of the Tasmania landscape evidences Anne Ferran’s command of the medium and signals a profound sensitivity to subtlety.

Most engaging in the 'The Ground, The Air' is the means by which Ferran negotiates the historical dimensions of site. A landscape almost totally desolate, it conceals a history that implores exposure. With particularly high infant mortality rates, the former Ross Female House of Correction is a place of boundless sorrow. However, what is most tragic is its almost utter disappearance. The lack of any physical trace that bears witness to the routine atrocity of the place is truly heartbreaking. Yet a memorial would seem utterly incongruous in this barren grassland. It is almost as if the ground had rejected the intrusion of the site, swallowing up any remains like a churning sea.

What Ferran recognises in 'The Ground, The Air' is the utter futility in representing trauma. Rather than imposing memorialisation, what Ferran presents is the impossibility of memory. Unknowable, forgotten and demolished, the Ross Women’s Prison offers no absolution, no resolution and no confrontation with the past.

Ferran’s representation of erasure is completely captivating to this extent. The success of 'The Ground, The Air' is not the creation of an artifice of memory or narrative. In restricting herself to the sparse, cold plains she confronts both the solemn history of the site and the horror of its disregard. It is a tragedy made more despicable through its forgetting.