'Nam Bang! is an impartial exhibition that does not take any political side.' - Wall text.

As a general rule, I am sceptical of the claim that anyone or anything can be impartial. Most of us cannot avoid being influenced by our various histories and experiences. However, in 'Nam Bang!' it is the diverse personal influences of the twenty-five Australian and international artists exhibited which lends credibility to the claim of the exhibition’s impartiality.

'Nam Bang!' is an exhibition of perspectives, of those who fought in the Vietnam War (including the Vietnamese, Americans, Australians and Koreans), lived through the war, escaped from the war and shared memories with family members who returned from the war. 'Nam Bang!' does not claim to be a complete representation of responses to the Vietnam War, because let’s face it, that could not be. Thirty-four years after the end of the Vietnam War 'Nam Bang!', the third in a series staged by Casula Powerhouse ('Viet Nam Voices' 1997 and 'Viet Nam Voices: Australians and the Viet Nam War' 2001), addresses the aftermath of the Vietnam War, particularly as it relates to the Australian experience.

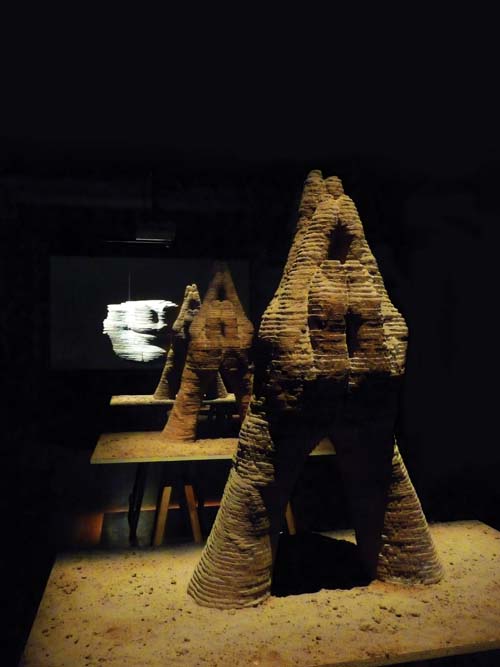

Nigel Helyer’s 'Silent Forest' (1996) permeates the exhibition space, in terms of space and sound. Large groups of speakers, modelled on the ones installed on the roof of the Opera Hall in Hanoi, project tangled sounds of air raid sirens and musical instruments. Glass beakers suspended beneath the speakers contain miniature rural scenes of people, pagodas and boats, each with its own tree being strangled and uprooted by orange wire - an obvious, yet poignant, reference to Vietnam being used as a laboratory for Agent Orange. Although surrounded by sound, the beakers appear to contain silence, an emptiness suspended in napalm-like jelly.

The music and percussive sounds of My Le Thi’s 'Encounters and Journey' (2009), a DVD work which explores the artist’s migration from Vietnam to Australia, intermingles with, almost in competition with, the unsettling air raid sirens from Helyer’s soundscape. Curator Boitran Huynh-Beattie says ‘if one feels the two soundtracks competing with each other, it might well be the metaphor of the ‘competition’ between the official and un-official histories [of the Vietnam War]’, a metaphor also evident in Shaun Gladwell’s 'They wake from dreams like the ones my father told me' (2009), William Short’s 'Memories of the America War: Stories from Viet Nam' (2009) and Soon-mi Yoo’s Ssitkim 'Talking to the dead' (2004).

The struggle between engaging the trauma of the war and creating a space for reflection is central to many of the works. Dinh Quang Le’s 'The Penal colony: A mapping of the mind' (2008) is an airless, purpose-built room, inside which full-scale images of prison cells at Con Dao Island (a French built political prison) rotate around the four walls. The uncomfortable heat of the projector and the sound of white noise is inescapable. Le’s visceral work tackles the confusion, physical and psychological pain, and trauma of prison and warfare, as do Trevor Woodward’s explosion of pattern and colour on canvas in 'What for, no more, where’s the door' (2009) and Dennis Trew’s disturbingly mortal photographs and text in 'Aftermath – Journey' (2009).

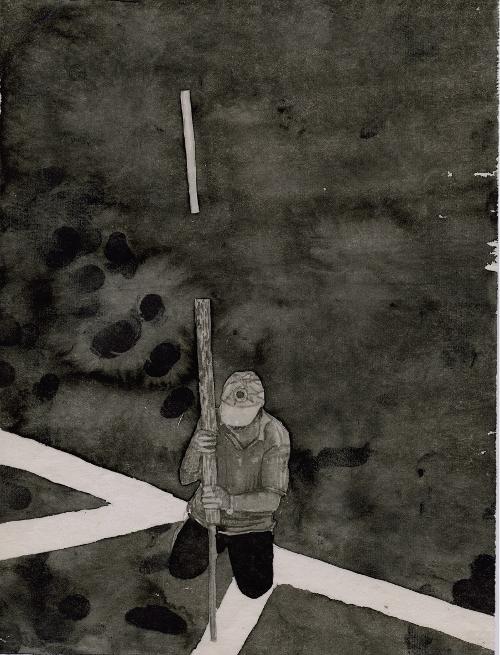

In contrast, Le Thua Tien’s 'Hands' (2008) emulate the steadfastness of an ancient relic. Clasped in the symbol of peace and prayer these topographical hands exude a sense of quiet healing similar to the meditative responses in Nerine Martini’s 'Heaven Net/ Luoi Troi' (2008) and Terry Eichler’s 'Meditation on 2,063,500 deaths' (2009). In Eichler’s work the act of markmaking on notepaper becomes a memorial to all who died during the Vietnam War, a way to grapple with the lives lost.

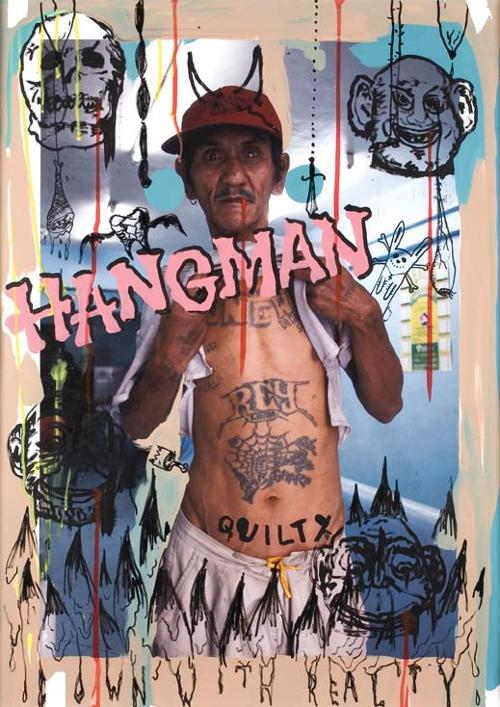

While 'Nam Bang!' is ostensibly about the aftermath of the Vietnam War, several of the artists, like Van Thanh Rudd, whose 'Portrait of an exploding terrorist' (2007) is a response to the Israeli offensive against Lebanon in 2006, address broader issues about the consequences of ‘modern’ conflicts. Each work in 'Nam Bang!' leaves, as Huynh-Beattie believes, an ‘after-taste’, the effect of which is a space where individual and collective experiences and memories of the Vietnam War can become sites of remembrance, discussion and reconciliation.