Constructing a jigsaw puzzle can be a satisfying if lonely occupation. An assurance that sorting and placing each separate piece will result in a perfect match with the image on the box allows us to think that every choice we make will eventually be the right one. In retrospect, we've had a reciprocal brush with destiny; a place for everything and everything in its place and we alone put them there.

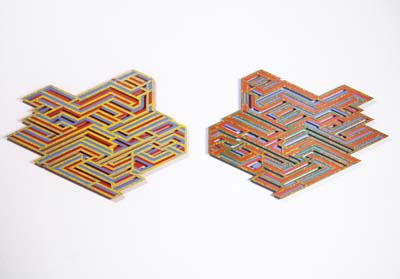

In the exhibition 'Paul Zika: Home and Away - reconstructing artifice' we recognise that a not dissimilar piecing-together process has taken place in the construction of each of these curious ornamental objects. But it has been skewed to disrupt an association with such homely comforting pastimes. These 'jigsaw puzzles’ are like the mouldy dog-eared ones of rented holiday houses, dug out of musty drawers to mollify disappointed children on rainy days. The initial challenge of having no box lid to give the game away being just the beginning of a series of creative solutions needed to continue. You wonder: are all the pieces there; are there too many; with a bit of a squeeze surely that one will fit; which side of this piece has the image on it anyway?

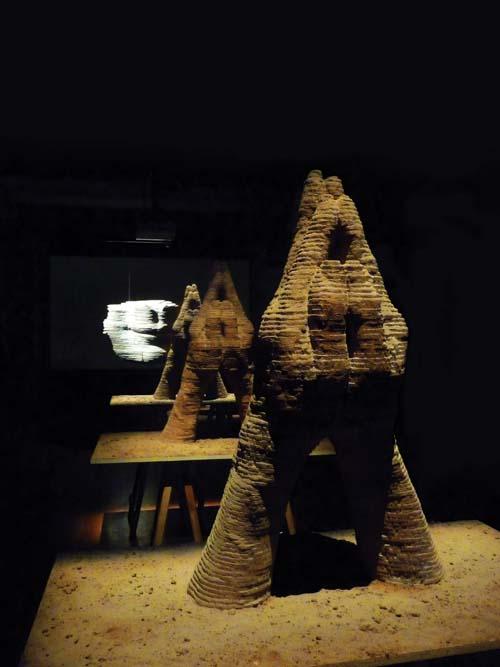

Works produced over the last twenty years of Paul Zika’s career, on display in Hobart’s Carnegie Gallery, have never been shown together before. It’s an exhibition of almost threatening visual overload, eccentric and audacious with kitsch Baroque references, revealing the influences gained from Zika’s travels abroad. Walking around the space, following an equilibrium induced by those works that rest at eye level, you’re interrupted by those that agglomerate toward the corners in vertiginous clusters. Are all the pieces there; are there too many? Certainly this arrangement goes against the trend of minimal exhibition design that suggests a tyrannical superego insisting on meticulous gallery ‘housekeeping’ or, to quote Edward Colless out of context, on ‘propriety that disguises the voice of desire’.

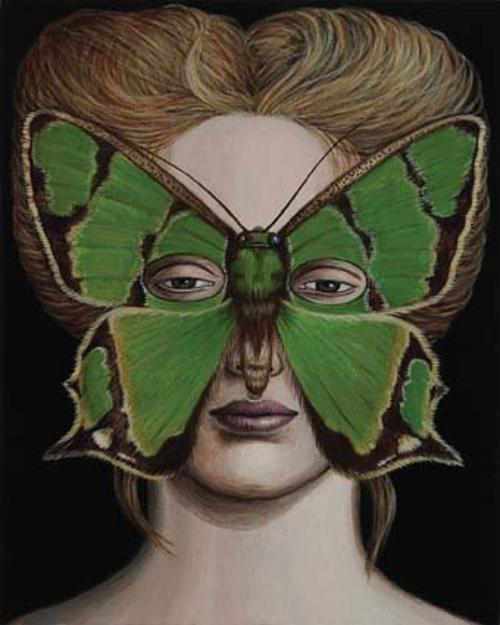

The luxurious busy-ness that fills the gallery masks a desperate sense of incompleteness; if you can’t find the right pieces to the puzzle can there ever be enough of them to choose from? Can these works be at home anywhere? As the curator Philip Watkins points out, they are ‘inverted camouflage’ revealing a structuring process that cannot locate its object. Even in terms of painting, the stippling, gilding and chocolate boxy brush strokes become ironic signifiers for painting, suggesting that it never had a monopoly on aesthetic integrity. Zika’s fragmented and punctured surfaces throw perfume on the violet only to frame the emptiness that flows through and beyond them. You might think that these multi-faceted works relate to their surrounding architecture but as in the mongrel box of jigsaw pieces, you can never really be sure how the edges or corners relate to one another.

There is an appropriately lavish, gilt covered catalogue accompanying this exhibition with texts from Philip Watkins and Edward Colless, both of which add considerably to the enjoyment of Zika’s work. The Lacanian inspired psycho-sexual extrapolation of Colless declares this artist’s work (if not all art objects) as desiring mechanisms. In this particular case the repeated concentric latticework is partly read as a threshold to unconscious desire; sexualisation produced by the resolution of the Oedipus complex through ‘castration’. This tour de force text, in part, cogitates on the latticework as a double-sided grille where the feminine and the phallic become differentiated. Here the generation of unconscious desire begins; the asymmetrical quest for wholeness between the sexes, which is a labyrinthine puzzle of having/not having the phallus.

Zika also produces hallucinatory ‘machines’ that have been ingeniously developed over the twenty years of his work that this exhibition represents. There is a lightening in the construction of the more recent pieces replacing complex layers built into the works with a play of shadows. From the earlier 'Monstrance' works that appear like cartoonish heraldic emblems (that may have just survived a dunking in the ‘toon’ destroying ‘dip’ from the film, 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit)' to the 'Tarabuco' series, in which the brightly coloured backs of each work, in combination with the lighting, produces a multiplicity of coloured shadows, 'Home and Away' provides the viewer with an intriguing perspective on the unfinished historical jigsaw puzzle that is the transition from Modernist abstraction to current visual arts practice.