Caitlin Yardley's exhibition 'spill: the insistent body', is part of the annual Tilt programme developed by the City of Melville to support a local artist, who is invited to respond to the Heathcote site with its many layered histories and provide engaging art to the residents and visitors of Melville. Yardley has focused on the period when the gallery functioned as 'Heathcote Mental Reception Home' for women, negotiating issues such as: institutional hegemonic structures, mental health, and in particular, issues dealing with the subjugation of women.

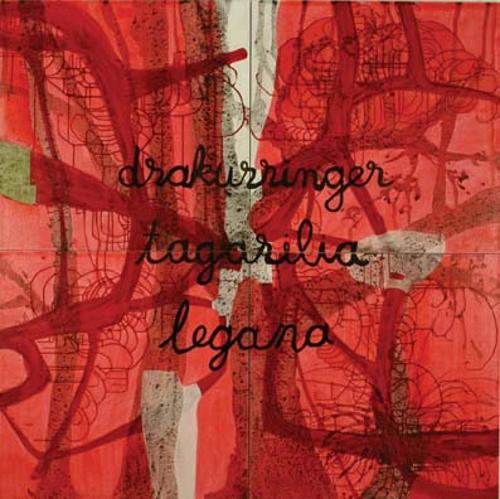

All of the works in the exhibition incorporate elements of paint. Painting, for Yardley, is used as an interventionist tool into which the historical function of the building and subsequently its contemporary meanings are examined. One aspect concerns the institutionalisation of women, and the other, the problematic patriarchal Western art canon of 1950s abstract expressionism. Although these two contexts may seem disparate, for the artist, they both provide a focus on repositioning gender.

It is not happenchance that Yardley focuses on the role of women at Heathcote. In previous exhibitions, nationally and internationally, she has questioned the lack of female representation within Western art. She challenges the physical, masculine approach to work with a feminist critique - referencing de Kooning – where, through the processes of pouring in her evocative works, she creates metaphorical links to the body. Caitlin’s paintings are sized and named after de Kooning paintings.

Upon entering the gallery, the viewer is confronted with a display case containing records from 1929 reporting the nightly activities at Heathcote, and a series of pipettes in small glass jars with paint staining their bases. The book introduces the work, contextualising the building’s former use, revealing patient’s names and associated incidents. On Friday 28th March 1929, it was handwritten, 'Troublesome at teatime, broke the cup and saucer, quiet this morning’ and another, ‘noisy and disruptive, had paraldehyde, slept six hours’.

This authenticity is heightened by Yardley sourcing stainless steel hospital trolleys from the Royal Perth Hospital Museum, Mental Health Museum of WA, and Heathcote itself. A series of borosilicate glass petri dishes, 'Cell Theory: Culture Dish I – XLVII' are placed upon the seven trolleys, one of which is inscribed ‘Female 3’, as a reminder of the object’s original function. The base of each petri dish is painted in oil resembling cells and cultures, this relationship to biology is a recurrent theme: blood, bacteria, or viruses – is it scientific research, or something more sinister?

In 'The Insistent Body', paint-stained paper towels in borosilicate glass bell jars, are Yardley’s attempt to domesticate the mess of a paint spill. Just as the paint cannot be contained (as evidenced by the amount of towels) so too, we cannot stop our bodies from oozing in ways we’d rather they didn’t. She reveals the pointlessness of this cultural obsession of trying to stop the inevitable signs of ageing or in organising our flesh so it appears more ‘acceptable’.

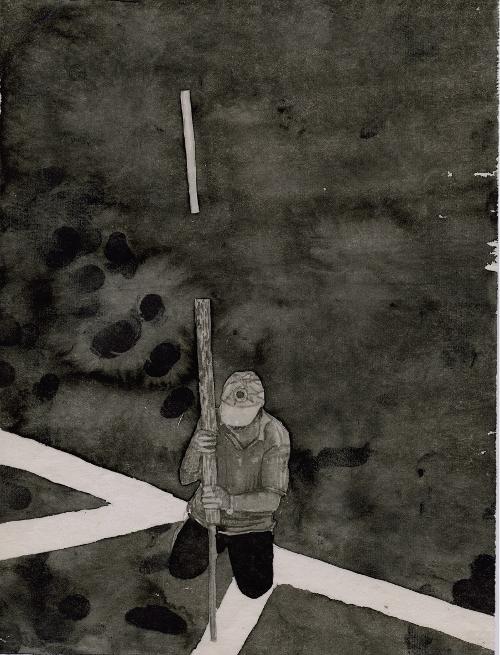

At no time is the audience afforded a view of the entire exhibition. This creates a feeling of claustrophobia, especially when viewing the work in the isolation rooms, however, it also promotes intimacy. One is confronted by a single large painting revealing Yardley’s exquisite use of colour, rich reds and green spills appearing like veins or arteries stain the canvas. In the other two isolation cells, the audience becomes a voyeur, as the only view is through the window on the doors. Spill Stack is placed in one of these rooms, revealing the significance of process – not about covering over, rather exposing the paint as detritus.

Although there are multiple ways of reading Yardley’s work, it is ultimately about the body and through the layered use of paint she constructs thought-provoking works that are at once beautiful, arresting and confronting. 'Spill: the insistent body' asks us to consider mental illness, and in particular female mental illness, not to be passive in this consideration, but to acknowledge the slipperiness of our interpretation of histories.