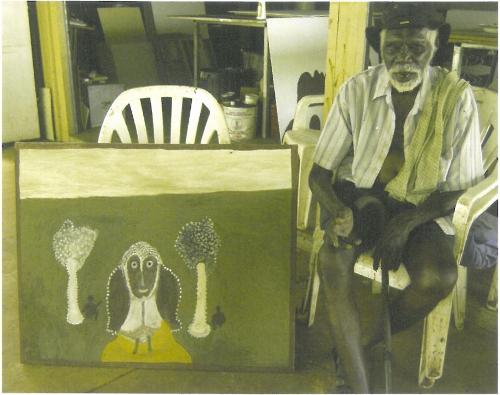

The haunting black and white photos in Roger Ballen's Shadow Chamber are like freeze-frame images stolen from the subconscious. It is as if his subject's hidden thoughts, dreams and fears are rendered visible by the camera's all-seeing eye. Ballen seems to document an off kilter parallel world, a grim universe divided into claustrophobic cells populated by freaks, dirty children with masks askew and animals performing meaningless stunts: a twisted fantasy, a nightmare, a carnival spinning out of control.

But photography's residual indexical nature is a reminder that no matter how transparently staged Ballen's scenes are, somewhere, out there, these rooms do exist. Ballen's bizarre tableaux are an illustration of the real world: an actual place reeking of poverty and desperation, furnished with stained floral mattresses, sagging couches and inexplicable tangled wires. Ballen's reality is a grimy place where smeared and splattered walls are punctuated by bursts of scrawled graffiti and unfortunate people seem willing to participate in their own degradation.

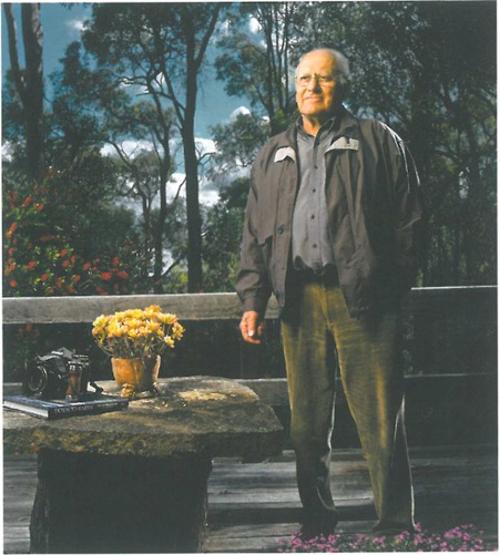

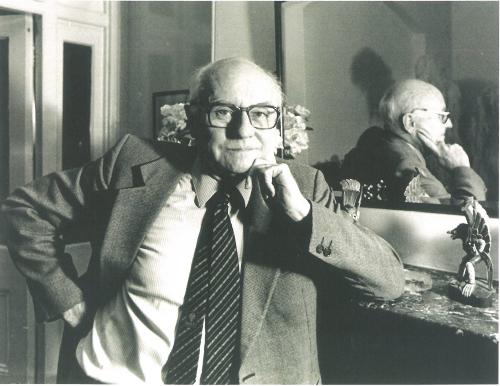

The physical location of Ballen's photographs is South Africa, where the American artist has been living and working for nearly thirty years. Photography runs in Ballen's family, his father was a picture editor for Magnum and Ballen began shooting his surroundings while still a teenager in New York. He has a degree in Psychology and a PhD in Mineral Economics. Somewhere along the line, Ballen picked up an unnervingly persuasive way with animals. In his photos, rats, snakes, cats, bunnies and puppies seem to perform on cue. And so do the motley crew of human characters that he finds in Johannesburg's edgier neighbourhoods.

Ballen seems to be drawn to outsiders, an obsession he shares with the late Diane Arbus. But while Arbus would photograph social outcasts in their natural habitats, using a fairly straight documentary portrait style, Ballen goes a step further by convincing his subjects to pose in highly orchestrated scenes; stories with their own agendas.

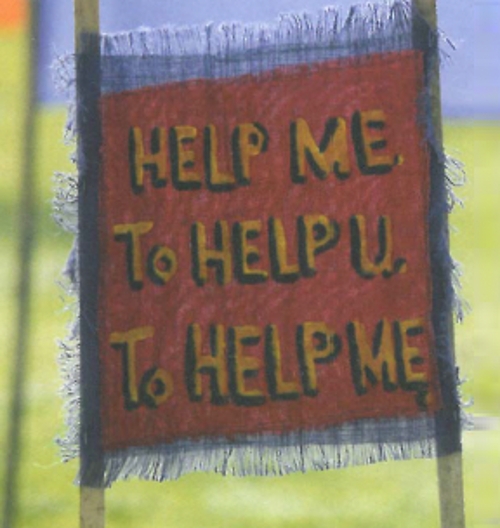

Ballen's photographs are an enticing contradiction, they are simultaneously dark, disturbing, and funny. In Loner, a man lies on a slumped mattress. Above him a crucified baby doll has been labelled 'God' in big childish letters, below a little white dog looks back at the camera like he knows something we don't. In Bent Back, a skinny old man in dirty, baggy shorts bends over a pot plant, ribs poking out at dangerous angles. His body forms a perfect inverted U, mirrored by a bent wire on the wall. A young man lounging on the floor cackles manically down the phone in Rat Cemetery, oblivious to the dead rodents surrounding him. In Birdwoman, someone in a faux fur coat, looking for all the world like a man, hides their face behind a white dove, while an erratic chain of coat hangers cascades down the wall.

As formal compositions, Ballen's photos are exquisite: a dynamic balance of line and shape, light and dark. But of course they aren't just aesthetic arrangements of abstract forms. These images are intriguing fragments of mysterious narratives. What is going on? Who are these people? They appear to pose quite happily, but do they know how demented they are being made to look? Do they care?

Many of Ballen's subjects are clearly a few sandwiches short of a picnic. In one such photo, Stefanus clutches two new-born pups. He looks vacant, helpless and vaguely menacing, a perfect real-time manifestation of John's Steinbeck's character Lennie, who unwittingly loves a puppy to death in Of Mice and Men. In Lunchtime, an equally blank looking fellow prepares to dine on a single goldfish. Are these people really capable of making clear decisions or are they just pleased with the attention? It is this ambiguity, the blurriness between coercion and cooperation in Ballen's images that makes them both fascinating and troubling. Either way, as viewers, we are forced into the highly charged position of watching people humiliate themselves. Now we are complicit too.