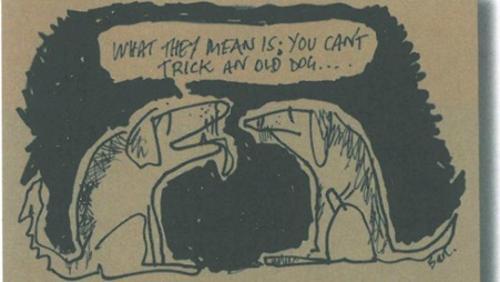

The traditional love/hate relationship with old people and the phenomenon of the shifting young/old demographic in advanced societies are not issues that have been much focused on in the world of art and artists. In contrast to many other professions and trades, the competence of artists to continue making good art into old age has never been challenged and they are spared the painful process of being made redundant and thrown on the scrapheap because they are 'too old'. Cynics may put this down to the fact that the vast majority of artists are self-employed.

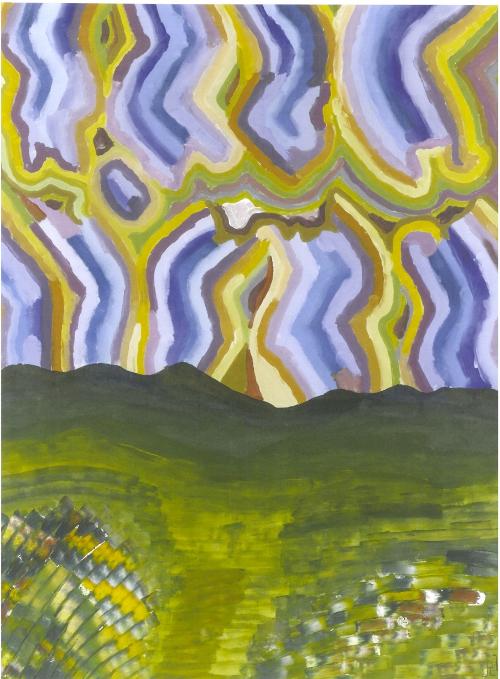

But despite the demographics, Australian society still privileges the young and the cool and there is not much room in the pantheon for the old and perhaps the wise. Who needs wisdom when we play out our lives believing that we can create whatever kind of lifestyle we choose whenever we feel like it? The fact that globally our chooks are coming home to roost and civilisation may be wiped out in a few decades is beginning to put a different spin on the notion of how we see the big picture, what we value, how we agree to share the planet.

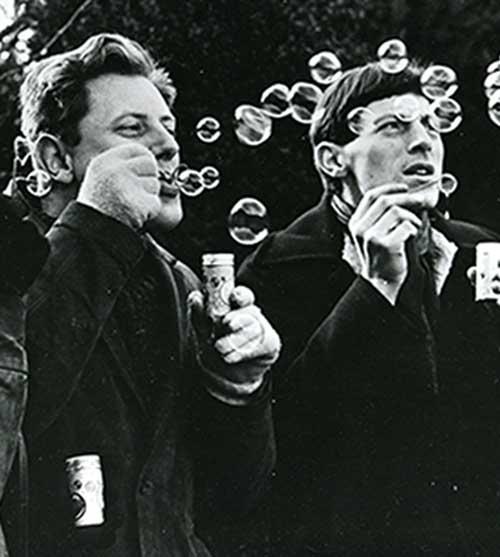

This issue of Artlink focuses on a generation of people who were born between about 1920 and 1930, inheriting the massive social changes of industrialisation that their parents had experienced. As post-colonial Australians, whether born here or arriving as post-war migrants or refugees, they had to try and make sense of the idea of Australia. They were still part of the making-do society, where what you achieved was up to you and you didn't expect a handout.

By the 1960s and 1970s they were making their mark, inventing ways to work in a society that was highly toxic to artists or cultural difference. Things began to change in the late sixties thanks to the brilliant work of Dr Jean Battersby, who helped invent the Australia Council and was its first Director, working with the enlightened public servant and economist Nugget Coombs. Between them they sketched out a framework for valuing of the arts. Battersby is one of many great elders still active in the field, but not often acknowledged, who do not appear in this issue, simply because the field was clearly far too large to include all who shaped our present day arts environment.

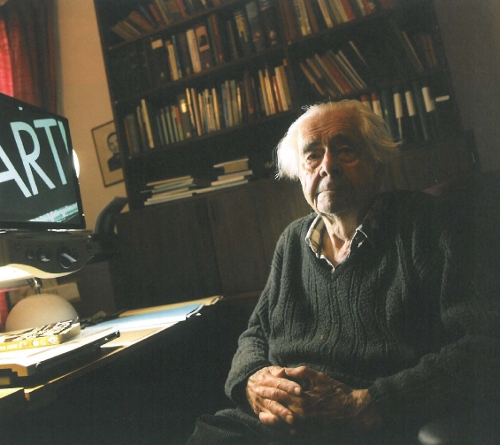

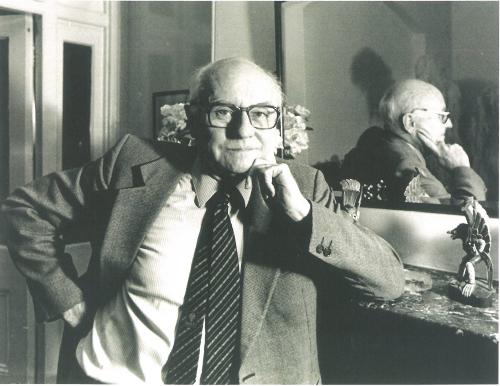

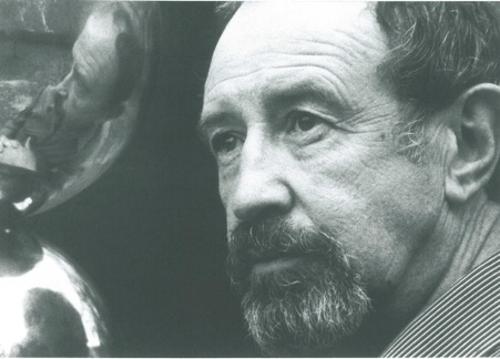

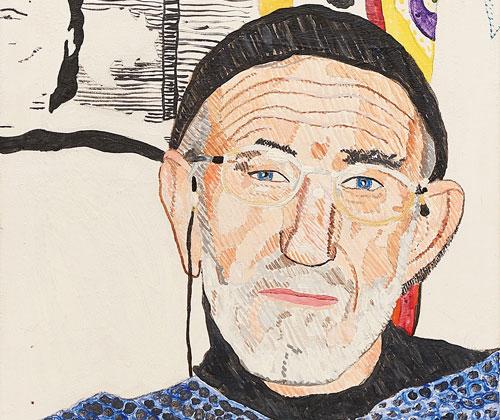

The people we managed to interview for this issue, some born only a decade or so after Sidney Nolan and Albert Tucker, chose Australia rather than a life lived in the shadow of 'overseas'. Thanks perhaps to good genes or modern medicine they have survived into their late seventies and eighties and are still producing work, some would say their best work. Those who were art school lecturers have influenced generations of students and an idea floated early on in this publication was to canvass some of these ex-students to ask how their notions of art were influenced by their charismatic mentors, but time and space did not permit. The keen organisational supporters of the interviews, (whom we contacted many weeks after the interviews had happened when it became apparent that we needed to add more pages to the magazine) attest to the role of these people in the creation of some of the institutions.

Thanks to scientific advances we are witnessing not only a generation of elders who are still actively working, but we are also starting to glimpse an explanation of the traditional concept of 'the wisdom of elders'. A recent Catalyst program on ABC-TV looked at the brains of people in their seventies and found an extraordinary thing. Although the grey matter, the 'hard drive' of the brain, had shrunk, accounting for the loss of the ability to instantly recall facts and names, the white matter, the 'internet' of the brain, had expanded. White matter is the neural network responsible for making connections and thus is a crucial agent of decision-making. Scientists have found that as we age the speed at which messages are transmitted across this network increases markedly. In addition the network itself increases in complexity, so older people can cut to the chase more readily, ignoring the irrelevant, bypassing the assault of the emotions, reconciling contradictions, and arriving at the decision which is the most effective and least damaging to others.

We have a great deal to learn about ageing but society is becoming dimly aware of what the elders amongst us can contribute.

It was Pat Hoffie who fielded the concept of Artlink tackling the Elders, and the important business of recording history before it vanishes, truly the job of larger and better resourced organisations. The recent decision of the ABC to dump Radio National's excellent program The Deep End, in which much vital interview material with living artists is recorded and thus preserved, is a disgrace. Rather than cutting back, our national broadcaster should be extending its responsibility for recording history.

POSTCRIPT

Artlink has this year reached its silver anniversary, and far from running out of puff, we feel as if we are just getting going. Expansion of the website will happen in the very near future and there are plans afoot for other projects. Thanks to all our loyal subscribers over the past 25 years. Keep up your subscriptions so you don't miss an episode in the ongoing saga of contemporary Australian art. To new readers, subscribe before 31st January 2007 and beat our modest price rise.