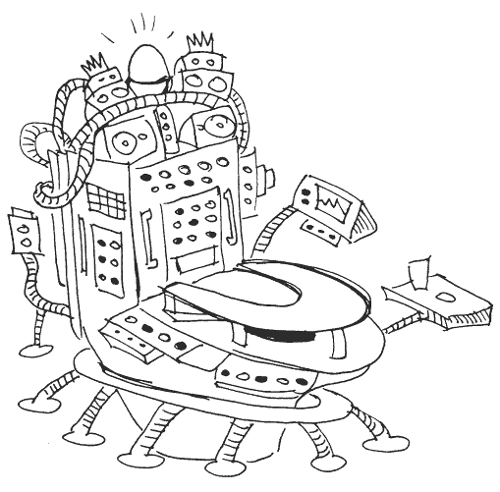

The emergence of 'new media' as an art form in recent decades builds on a rich history of cross-disciplinary art practice. New media is typified by its inclusiveness. Not only does new media draw on a broad variety of artistic practices and disciplines, but new media and digital technologies have also had a wideranging impact on already established art forms, in many cases transforming and re-invigorating them in fresh and unpredictable ways. While many artists would not necessarily define Editorial themselves as new media artists, an increasing number of artists are using new media technologies in their work. The cover image of this issue, Ricky Swallow's new work iMan Prototype (200n is a case in point. As always, artists will use whatever tools suit the purpose at hand, often crossing art forms to do so.

Since Artlink's Arts in the Electronic Landscape issue in 1996, and the even earlier Art and Technology issue in 1987, we have all become more fully immersed in digital culture. New media technologies permeate our lives at every level from the workplace to the home and the realms of culture and entertainment. With mobile phones and the Internet added to our already extensive forms of mass media communication, we're entering an era of info-glut and communication overload, of global culture and information flows where we're all on '24-7' - twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. In this brave new world of rapid 'progress', technological hype and e-words proliferate. Mercifully we have, as yet, been saved from' e-art' in the shift from electronic art to digital media, and now to new media art - with other contenders like intermedia, multimedia and hybrid media popping up along the way. The shifting terminology indicates the fluid and contested nature of this new art form which occupies the interstices of already existing art forms and hungrily engulfs new technological developments as they come online. For some, the term 'new media' is itself redundant - simultaneously everything and nothing - due to the pervasive nature of digital technologies and the inevitable progression of 'new' media into 'old' media. Nevertheless, there is still a case to be made for new media as an art form, albeit one with indistinct boundaries. Indeed, it is the very convergence of audio-visuat computing and communication technologies that simultaneously defines this area and enables and encourages the permeability of boundaries and resultant hybrid practice.

New media art is very much'art of its time' using the tools and languages offered by evolving new technologies to critically and creatively engage with our screen-based, media-saturated culture and its obsession with technological innovation and 'progress'. The promises and anxieties entailed in these developing technologies, from globalisation to our increasingly intimate relationships with technology goes to the very heart of what it means to be 'human' in the coming century. Scientific and technological developments have moved centre stage to become key concerns for artists working with new technologies. The resonance these concerns have in the public arena can also be seen in the growing popularity of thegenre of science fiction, which has left behind its B-grade status to enter the cultural mainstream.

Just as cinema and television were the defining cultural forms for the twentieth century, new media - the 'new kid' on the block in the art world - is emerging from an accelerated adolescence, to stand centre stage in the international art arena in the twenty-first century bridging the gulf of popular screen culture and the fine arts. While cinema and television had difficulty in shaking off their popular or 'low' culture overtones due to their prohibitive production costs and need to appeal to as broad a public as possible, new media technologies are far more accessible to individual artists offering an extraordinary variety of 'tools of the trade' and presentation methods from the intimate experience of a website or cd-rom to large-scale installations and projections, 2D digital prints, 3D digitally designed sculptural objects, video, sound and performance.

While interactivity is not necessarily a defining trait of new media art, it has undoubtedly generated some of the most interesting developments in new media work, encouraging a 'hands-on' interaction which runs counter to the 'look but don't touch' approach of most other art forms. The participation of the audience in the artwork, although not a new feature of the visual and performing arts, is greatly enhanced by digital technologies. The number-crunching ability of computing technologies combined with their connectivity allows sophisticated new possibilities for interaction as audience and artist inputs can be fed back into the artwork or performance to generate new outcomes in real time. As well as the mouse-driven point and click we are familiar with from cd-roms and websites, artists are also experimenting with voice, vision and movement activated systems that will allow new forms of audience engagement and interaction. It is in these areas, along with on-going developments in virtual reality systems, that we will see some of the most interesting new developments in the evolution of new media art in the next few decades.

Global flows of culture and cross-cultural exchange have been enhanced by new media technologies which have enabled new forms of collaboration and exchange by artists and cultural organisations. The facility with which new media work can be reproduced and distributed on cd-rom, video, dvd or the Internet, has increased the exhibition opportunities for artists, who can duplicate and transport their work with ease.

Commonwealth and State funding agencies along with tertiary institutions and screen culture organisations have played a key role in training artists and supporting the development, production and promotion of new media work. The current challenge is to build the necessary infrastructure to exhibit this work for a broad range of audiences across Australia.

In 1996, at the time of Artlink's Arts in the Electronic Landscape issue, many artists and cultural organisations were only just starting to use email. Now, in 2001, email has not only become a key communication tool but most organisations either have their own websites or are in the process of developing them. This increasing familiarity with new media technologies has helped to make cultural organisations and audiences more receptive to the exhibition of new media artwork but many organisations are still struggling to access the equipment necessary to host new media exhibitions.

New media technologies, both as art works and educational displays, are being incorporated into the design of new museums and art galleries such as the recently opened National Museum in Canberra and the new Australian Centre for the Moving Image scheduled to open in Melbourne in 2002. What we need now is a corresponding development of infrastructure in existing galleries and museums. Just as businesses need to factor in the costs of equipment purchase and upgrades, so too do cultural organisations and this needs to be recognised by funding bodies at local, state and federal levels. Without this infrastructure support, including access to both equipment and training, the new media arts will be relegated to a small number of hi-tech venues located in the main city centres of Australia. And that would be a shame for both artists and audiences.

This issue of Artlink provides a broad snapshot of the new media arts in Australia from funding bodies and organisations supporting new media to the work of individual artists working across the disciplines of performance, writing, sound, installation, time-based media and the visual arts. The importance of lively and engaged discourse to nourish and critique this emerging area cannot be underestimated. There is no doubt that the on-going evolution of new media will be a key factor in shaping the cultural landscape of the coming century.