This exhibition was organised by the Art Gallery of Western Australia as a companion to the Modern Australian Women: paintings and prints 1925 - 1945 which was showing concurrently. Although some Western Australian artists were included in the major travelling exhibition, such as Kathleen O'Connor and Elise Blumann who have had repeated showings here, Creating a Place provided the opportunity for the gallery to exhibit a number of strong but lesser known works by women artists from its collection.

The varied curatorial selection was made possible by the exhibition's title in that artworks did not have to conform to any overt sense of being modern. In fact the title had a degree of ambiguity for those with some knowledge of local practice. Is it a 'place' in the historical cultural life of Western Australia that is being established here, or a 'place' in the sense of domesticating an environment? For example, I was surprised by the inclusion of crocheted doilies, similar to ones made by my grandmother. I thought "That was a brave curatorial decision!", but then, "Why not?" The doilies (1930s) by Ivy Holcroft, and Marjorie Ridley's serving tray and containers made from plaited and dyed Guildford grass (1940s) are usually seen in museum displays of local craft. Other works which contributed to the creation of a 'domestic' place were the examples of china painting. I have always been uneasy about Marina Shaw's black-figured vases (1930s). These are literally traditional classic Greek vases (probably commercial blanks) painted with Aboriginal designs and figures. Maybe the artist had her tongue firmly in her cheek, who knows, but the clash of cultural motifs is jarring, and now, seventy years down the track, there are the issues of political correctness and appropriation to contend with. However these, and some of the other art works, raise some necessary questions and give this exhibition an edge that would otherwise be missing if the selection had been less risky.

Twenty four women artists were represented with works produced in oils, watercolour, sculpture, prints on paper and fabric, ceramics, china painting and weaving. There were some highly accomplished women printmakers in WA during the 1920s and 1930s and Beatrice Darbyshire (1901-1988) was well represented by some excellent prints and drawings. A small work in drypoint, The Silver Terrier (c.1930) brilliantly captures the wirey-ness of the dog's coat and its bright-eyed sharpish character. Darbyshire and a number of the other artists including Flora Landells, Florence Hall and Amy Heap, were attracted to the majestic nature of the tall timbers in the State, indicating many sketching parties into the bush. Despite the assumptions about women artists being constrained in their practice and sense of 'place', historical research, to the extent it has been undertaken in this state, suggests otherwise. Many were independent minded and were out in the bush recording the flora with their watercolours, or hewing large pieces of furniture and decorating these with carvings. Perhaps being a modern woman was as much about being free to follow one's convictions as an awareness of current cultural trends.

The landscape tradition was particularly dominant in Western Australia, almost to the exclusion of the city as an alternative subject. Harold Vike was an exception to this and Portia Bennett who often chose high vantage points to record the buildings and streets of Perth. Her Howard Street, Perth (watercolour, 1934) is typical of a Bennett cityscape in which people are very much secondary to the built structures. Bennett confirms the sense that pre World War II Perth was not a bustling metropolis, but a pretty country town redolent with sunlight falling on sleepy streets. By comparison, particular contemporary photographic images of Perth (by male photographers, and not part of this show) reveal the impact of modern European photography which could turn (a benign) 'Sleepy Hollow' into dynamic New York.

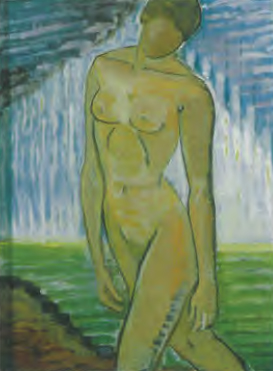

Much more gutsy, and unusual in the context of the Perth art scene during these decades, are the works of Elizabeth Blair Barber (b.1909). Her individualistic approach to form created with slashing brushstrokes endows the Portrait of Audrey Greenhalgh (c.1950) with high tensioned nervous energy. Through her training and travels abroad, Blair Barber was exposed to the international art scene, and it is this that may have sustained her uncommon style in a highly conservative home environment. A recent retrospective of her work has assured Blair Barber a place in WA's cultural pantheon. Unfortunately, the absence of a catalogue denies us the hidden story lines behind these works.