Here in Adelaide we're used to going to the Showgrounds on other occasions besides the still-Royal Show. There's the Red Cross Opportunity Megasale, the Earth Fair, various liquidation sales of assorted items across the year. And at Festival time it's one of the performance venues. But not, so far, for art exhibitions. For most of us, the space is filled with childhood associations of large, steaming animals, lurid sideshows, beefy logchoppers, and cakes in glass cases: the country come to town .

MA graduating students Flint, Golda, Harms, Phoenix, Radok, Robinson and Sleziak had the very bright idea of colonising this evocative place for their graduating show. Going to see it involved getting a map and embarking on a journey, from dairy- pavilion to sheep-pavilion, cubby-hole to tack-shed, handicrafts hall to arcaded auction room. This pilgrimage, in the Lost City of the deserted fairground, was part of the experience: many-layered, diverse, but reverberating at all points with muted longing, anticipation, nostalgia, a certain tristesse.

Lisa Harms' inhabiting of the Dairy Pavilion is a case in point. She lined the drains running the length of the stalls with heaped salt, stacked the empty mangers with pillows (inscribed: "Tell me a Story"), ran black-and-white videos of fluid, harmonious, imagery - milk sliding in a bucket, filigreed leaves - and furnished a tiny room with a salt-heaped floor and two iron frames, reminiscent of bedheads, dressed with sheer, stitched fabric. Halfway down one side of a corridor was a piano, keys removed, filled with dry leaves, and, opposite, a stack of cardboard boxes, some containing books of book-excerpts. A rustling noise came from above. The salt is a marker of (water's) passage, as well as a preservative. Harms' intent was to evoke 'a ruminating pause'. But she also calls up presences, ghosts, the past laying claim to our psyches. There was a palpable drama about this installation, a mise-en-scène drawing the onlooker into a somehow gothic dimension: strongly emotive, visually absorbing, keenly attuned to the space. It's possible there were a few too many elements in this work, whose strong bones didn't need overmuch adornment - always a temptation when work is to be assessed for grading.

Julie Henderson's Stirring Still was in the adjoining corridor, where, as in Harms' space, clean sawdust filled every stall. A music loop, swelling, descending, hypnotic, worked strong atmospheric magic as a video loop of half a dozen frames of the artist, seated, head on folded arms, turning sideways, front-on and back again before a blank wall played over and over onto a suspended sheet near a doorway. Again, the pre-existing empty, serially-populated building was factored in to the whole. Henderson's work was daringly minimal, the repetitious sensory data operating moodily, subliminally, to focus her concerns with embodiment, motion and stillness.

For Frances Phoenix, Agnieska Golda and India Flint, a strong folksy mood seems to have taken them over - in response, one supposes, to the influence of ghosts of herds and herders past steeping the showgrounds buildings. In the Sheep Pavilion. Phoenix made witty, topical use of a cavernous space, barricading off the unused half with a cyclone wire fence sporting tufts of 'rabbit' fluff, while her side of the shed housed items like stacked bullhorns, a mirrored plinth, a pig's ear, inside individual pens. Beneath a row of bleachers sat a stuffed black rabbit, provided with water. A giant, elongated rabbit 'shadow', painted across floor and shelves and up a wall, dominated one end of the shed. Other materials were canary seed, straw, and railway lines disappearing into an open cupboard. Susan Hiller's From the Freud Museum is referenced as a source for 'Rabbit', whom Phoenix has returning 'to exhibit her arts in the Pavilion'. The abject animal corpse, the art of death are Phoenix's obsessions - invoked both ironically and powerfully.

In a set of adjoining tiny sheds, Agnieska Golda stationed items such as a large, suspended straw doll with tarred-on breasts and pubic hair; foam mattresses layered to look like wagon-lit bunks, bits of bread stuffed between them; a set of crocheted stockings hung on a peg, a skirt piled on the floor as if just shrugged off; candles, stencilled folk motifs. She deftly, jarringly juxtaposed fairytale emblems with those of more recent horror-stories of journeys through European landscapes, querying the self-imaging of the 'folk', brutality hidden in pastoral romances.

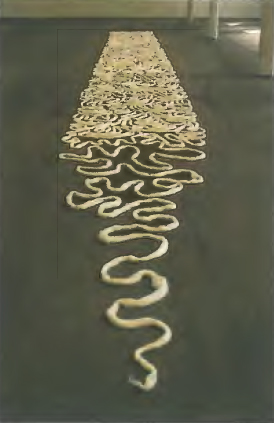

In a similar vein, India Flint staged an elegant meditation on the folktale journey-through-the-forest. In the Sheep Sales Hall, she hung long, floating white muslin garments on coat-hangers, laid intricately-woven trails of white wool the length of the floor, scattered a dusting of snow-like wool on sand in a doorway, hung photos of Eastern European destinations and signed them 'travels with a red felt ball' - the felt dyed with eucalyptus. Flint's light touch, the airly-indicated themes of migration and return, the eternal straying from the path of successive Red Riding Hoods - maze, Quest, song, snow, story, weaving - are perfectly judged to charm, intrigue, amuse.

Zofia Sleziak also recounted lost tales, her found transparencies, holiday snaps, sitting in light-boxes on stacked produce-boxes in shadowy cubby-holes, with a mellifluous voiceover tape-loop describing the scenes. Sleziak is interested in audience-participation, the filling-in of narrative detail provided almost involuntarily by the viewer, her images and objects staged to provoke 'perennial whispers'.

Stephanie Radok's use of the handicrafts hall involved hundreds of red-and-yellow watercolours of simple plant-forms inside the vitrines, all in fact South Australian flora, but labelled with the names of each country in the world. Some are superscribed with botanical legends. In other cases are plaster tiles stamped in reverse with archetypal book titles like The Invention of Tradition. Large canvases, impressionist, pastel renderings Australian coastal and desert landscapes, cover the walls. The whole is an original, potent, inclusive hymn to the world, lyrical and uninhibited, celebrating both the bounty of Nature and the tireless inventiveness of human signposting of it.

Fecundity, the Pastoral, husbandry and agriculture, domesticity, trade, travel, cycles of life and productivity, death/slaughter and rebirth, these seven bodies of winter work were wittily, arrestingly engaged with all these. All seven women forsook urban, edgy options to embrace an earthy, daringly un-hip alternative. It worked.