In the current climate, where the arts always seem to being served notice in the harsh world of economic rationalism, the City of Maroondah deserves commendation for opening a new Melbourne public contemporary art space in a 'Jeffed' former state school, now the 'Federation Estate' housing a gallery, a cultural centre with studio space for both individual artists and groups, and also a community centre serving welfare and social groups. The curated gallery is located in the most formal and traditional section of the complex, the early twentieth century red brick school buildings. The high ceilings, timber floors and wainscoting lent themselves to conversion to a quintessential gallery space. The first year program is an ambitious roster of touring and internally curated exhibitions.

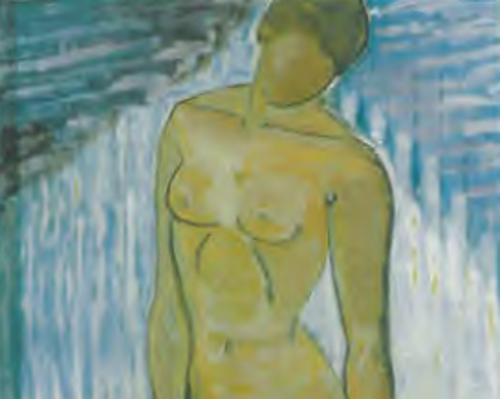

The first two projects generated by the Gallery itself were complementary presentations of women artists with substantial Melbourne and Victorian public profiles, Allure, the Feminine in Print and Pamela Irving Memory Ware. Allure was guest curated by Di Waite. The central theme of a post 1970s, pro-theory-and-Madonna feminism involving female sexuality and a femininity defined neither by victimhood nor defensiveness is a fact of contemporary art experience as much as an exploratory gesture. Allure made visual and theoretical sense because it drew upon a recognisable vocabulary. Previously Deborah Klein's work, for one, has been discussed precisely in context of post-1970s feminism. Likewise there has been an established ongoing recent tendcency in Melbourne of artists known for other media crossing into textiles, and combining fabrics painting and printmaking. With computer generation – particularly seen in Marion Manifold and Wendy Hutchison - and collage of fabrics, nets, voils, interfacing, even foil and metals, it also demonstrated how the printmaking envelope has been expanded in the last twenty years. Again this is an acceptible art practice as much as rebellious defiance.

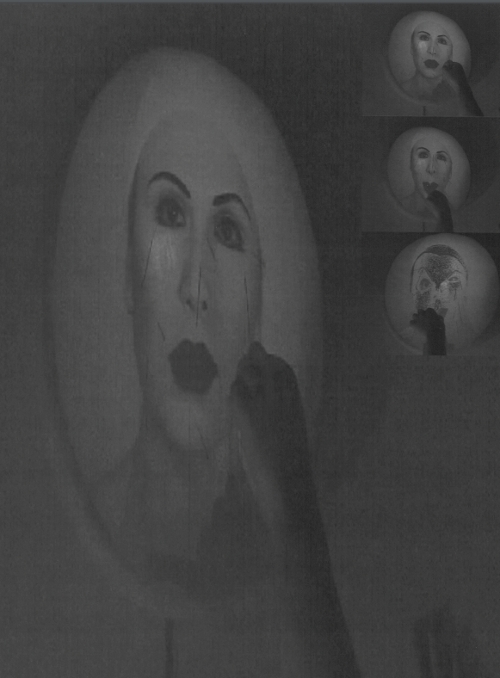

Despite their overtly playful character Pamela Irving's sculptures in the second gallery raised faintly disturbing questions about where the female placed herself in relation to the voyeuristic gaze and the white noise of popular sexual vulgarities and teasing, whereas Allure spoke of a shared language between artist and theoreticians and of a space where the feminine speaks fearlessly as the mainstream. Klein's work infers a less traumatic interchange between the feminine and surrealism than does Irving. The women in Klein's prints are confident and firm in their identity, which includes a strong respect for nostalgia and tradition. Elsewhere Klein has portrayed Joan of Arc and other female martyrs recast as powerful women. Irving's ceramics speak of darker gender tensions in Australia. Her dogs follow a widespread modern Australian imaging of the working class, male and larrikinesque as a bawdy, cheeky dog, popularised by the Mambo group. The chunky physical presence of her sculptures contrasts with the felicitous detail and wit in the mosaic. Irving deploys broken china with flair, informed simultaneously by ribaldry and nostalgic patterning. This sensitivity to the visual and associative pleasure of pattern is shared by Klein, Shimmen and Manifold in the neighbouring gallery, making the pairing of the two shows persuasive. Irving and Shimmen held recent joint exhibitions in Adelaide and Melbourne. Both artists are bricoleurs ever alert to visual double entendres in the popular and spurned.

Unlike the unified feminine focus of Allure, Irving's work morphed between male and female sexualities. For her inner yob, teapot spouts are ready-made dicks and teapot lids ready made tits, whilst her inner princess revelled in the undervalued femininity of escape from the overtly crude: glory boxes, old country roses and ballerina statuettes. The detail, choice and selection of shards in Irving's sculptures produces sharp social commentary, which simultaneously parodied and poeticised/celebrated the world of Menzies' "forgotten people". But the violence implicit in the broken shards infers that the comfort and sense of self-worth of Menzies' generation was founded on the nihilistic destruction of the Second World War, their hands only washed by victory soap. Shattered Australian souvenir ceramics of the 1950s and 1960s also speak of cultural displacement, as well as the changing tides in nationalism and its protocols. That Irving sees her work in term of this broad historical landscape is demonstrated by her ongoing creative fascination with Ned Kelly and Princess Diana. Her use of Kelly subverts and transgresses the aura of cultural and political sanctity that masculine fantasy has woven around Kelly and forced onto Australian public culture. Whereas Allure presented an Australian world that was post-feminist, post gender combat, where female values can flourish unapologetically and with total credibility on central stage, Memory Ware suggested that the feminine in Australian public culture must play a tricky volatile game of divided loyalties.