The trace of fire, the cast of a shadow, the feel for earth, the touch of the hand - all of these elements will confront, calm and captivate visitors to this alluring and memorable survey exhibition by South Australian artist Hossein Valamanesh. The showing of sixty works and documentation of another seven permanent and ephemeral public installations spanning more than twenty years of practice is the result of the timely and generous commitment of the Art Gallery of South Australia and curator Sarah Thomas to honour one of the country's most dedicated and talented artists.

As Bruce James remarked in his opening address to a packed audience in late June, Valamanesh is an artist who takes his time, and in his unhurried manner has divined and given visual form to so many human conumdrums. James' thoughtful speech prepared us for an amplification of the enjoyment and appreciation that so many Adelaide art lovers have experienced over the years at the numerous presentations of this artist's work.

Having been away from Adelaide for so long I am glad to have the opportunity to experience this exhibition at first hand where numerous works seemed to be in quiet conference with each other. This last quality is important to draw attention to, as it is a very rare artist indeed who confers upon his materials such an uncanny sensitivity, clarity of purpose and unfaltering lightness of touch over a body of work that spans more than two decades of production. The creative acts, the leaps of faith and the discipline that bring about art permeates this beautiful presentation like a sustained mantra.

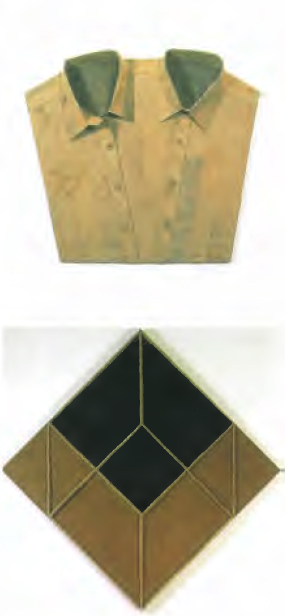

I can still recall the breathless surprise evoked by coming across The untouchable (1984) and Empty cube (1985) on the central floor of the unforgivingly angular spaces of Macquarie Galleries, Sydney in 1985. One finds these two works, along with the agricultural tensions of the seminal 1981 work, Pyramids with light - inside/outside, not only fortuitously reproduced in proximity with one another in the catalogue, but also forming part of an installational spine to a significant portion of the exhibition.

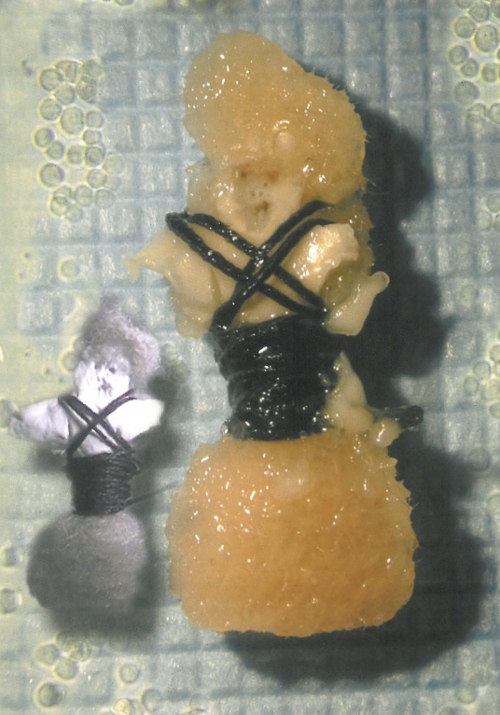

On a tactile level, edges of all varieties - sewn, drawn, torn, hewn, twined, tassled, gyrating - most wrought by hand - are imbued with a sense of the loving human touch, and the imprint of the artist's own personality. On a formal level perhaps is it the close encountering of the natural, textured surfaces of much of the work, untrammelled by reflective glass and restraining barriers, that also gives this exhibition its unity and powerful appeal. This is particularly apparent in works such as On the way (1990) and the roughly applied yet masterful penumbral tones of Shadow of a cloud (1992), both of which catch the eye and beckon a closer viewing.

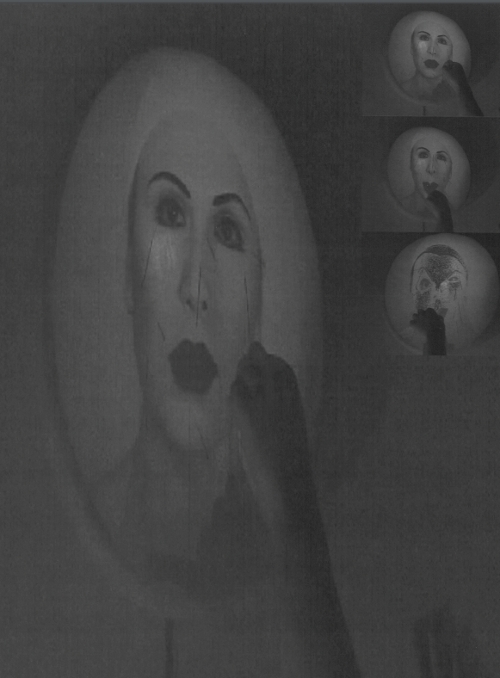

The Birch song cycle of 1991, with its combinations of water and synthetically produced sounds, permeate and create a curiously sympathetic atmosphere for viewing the many moisture-leached productions on display. One also finds oneself at times in the midst of pieces. That it to say, the sense of restoration and reanimation of many of the works, unpacked from long storage, and rejuvenated by the tender focal points of candle flame give them a seductive, living presence. One exception to this is The lover circle his own heart (1993), which seems quite deadpan when compared to its original documentation. Thankfully its mesmeric photographic documentation, in a catacomb of a Polish castle where it was first shown, has been reproduced prominently as a catalogue illustration and in gallery publicity.

The extended labels that accompany works are generally models of restraint, helpful without being overly didactic, although I was puzzled to find that Untitled (Ladder) 1999, in the wall label and the catalogue entry overlook any reference to those haunting, staring glass eyes, surely the surrealistic fulcrum of the piece.

The catalogue, beyond the province of this review, despite a few very minor lapses, will provide a significant reference point for the appraisal of the artist's work in years to come. One of its features is that it does not follow a strict chronological sequence of the artist's development, which lends an element of surprise to its perusal, and conveys a sense of the doubling back and revisiting of themes and formal solutions by the artist himself. Readers can turn to three quite different and complementary essays that locate Valamanesh's practice in a variety of contexts, and the extensive bibliography and useful exhibition history checklist embedded in the catalogue of exhibits demonstrate the rigour brought to bear on the enterprise.

We are to be thankful for this significant staging post in the artist's career, in the knowledge that it gives both priceless time for the artist as well as viewers to reflect on his achievements, and perchance, to contemplate what the next two decades may bring.