A house without a television is a very spooky and uncomfortable place to be.

- Stephen Marinovich, "Turn on the TV and tell me that you love me" in Craftwest 2000

Being a television addict I agree with Marinovich. And so, as well as being familiar with why Joey will never truly get over Dawson, I'm familiar with the fact that the debate surrounding that flickering magic box I spend my evenings transfixed by is preternaturally dull, if heated. For every wide-eyed Raymond Williams believing it to be a potentially liberatory medium for the masses, there's some disposable hero of hip-hoprisy for whom it's the dangerously addictive drug of a nation. Though influenced by the process of plonking down in front of the boob-toob, Caspar Fairhall's latest one-guy exhibition at Galerie Dusseldorf manages to neatly side-step these tedious binaries to offer something far more absorbing.

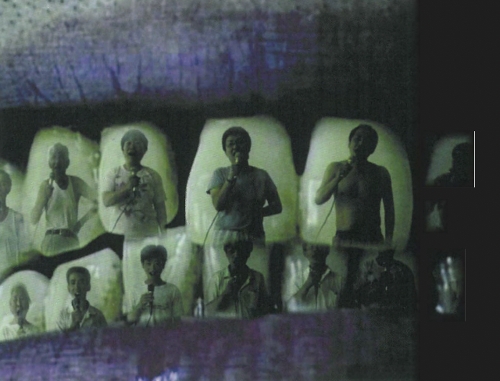

This is undoubtedly because his slice of predominantly abstract paintings (imagine Angela Adams doing a Bridget Riley, or vice-versa, or early Balson on ecstasy) and his set of (rather less well resolved) black and white computer-generated pieces are inspired by the test pattern. Because of this too, a faint (though not unpleasant) moth-ball whiff of nostalgia hung over them. SBS and community television at night aside, just how many years has it been since there has been such a thing a test pattern on our screens? How long has it been since there's been 'nothing' to see?

In his artist's statement, Fairhall justifies his engagement with our test pattern memories in the following terms: "the test pattern in particular interests me as it is used to calibrate the television, but in doing so turns a TV from an instrument of realism into something closely resembling certain strands of 20th century abstract painting. To me this is like a crack in the illusion that shows the artificial nature of the medium". Frankly I'm not so convinced of that last bit.

As a whole we're a canny bunch of square-eyes and even the most naive of viewers amongst us knows that televisual realism is coded and constructed. Today, the test pattern is hardly akin to Slavoj Zizek's "blot of the Real" that allows us to slip behind the Symbolic. This aside, it is potentially just as confronting: the test pattern once made us television orphans, forced us to take responsibility for our lives again. As he alludes to then, Fairhall's images investigate the status of (modernist) disinterested pleasure. Both the test-pattern viewer and the proto-typical (if in reality non-existent) modernist spectator are unified in their severance of a proper investment in what they're perusing. But Fairhall doesn't leave matters there, because the uncanny thing about his works' obvious aesthetic appeal is that they lure us to stay-tuned anyway. As they do, the nostalgic spectre of the test-pattern comes back to haunt us like the return-of-the-repressed, grabbing us (in its re-incarnated form) in the more complex push-me/pull-me dynamic of an uncomfortable rapprochement.

That Fairhall is harking back to the past to re-stage an analysis of the difficulty/absurdity of a truly divested (hi-mod) gaze at a time when the 'everyday' has taken hold of the art world by the jugular is curious. Just maybe, though, his paintings simply remind us that the everyday takes its logic from the constructs of the art world, that its 'freedoms' are relational, structurally bound. So from this, they may also be encouraging us to begin investigating the "formalist repressed" in the art of the everyday. If so, Fairhall's works are oddly Malevichian, boldly leaping out into the world that organises itself around their forms and yet, staying, perversely, doggedly, put. (The work of art as couch potato?) This said, probably not even Malevich could have predicted that that frustrating half-hour of test pattern hell between Gilligan's Island and I Dream of Jeanie would end up being so important.