The politics of spectatorship are complex and in need of perpetual redefinitions within the spaces/places deemed 'public' and 'private'. Often sites envelop both public and private codes. The genre of portraiture, like documentaries, has become a discourse blurring once disparate and discrete categories between fact and fiction, public and private. This is highlighted through media such as TV and the internet which operate through devices such as familiarity, intimacy and immediacy to further mix codes between local and global, trivial and sublime. From this context, how can contemporary 'types' and ensuing ideologies surrounding spectatorship be rethought and reconfigured?

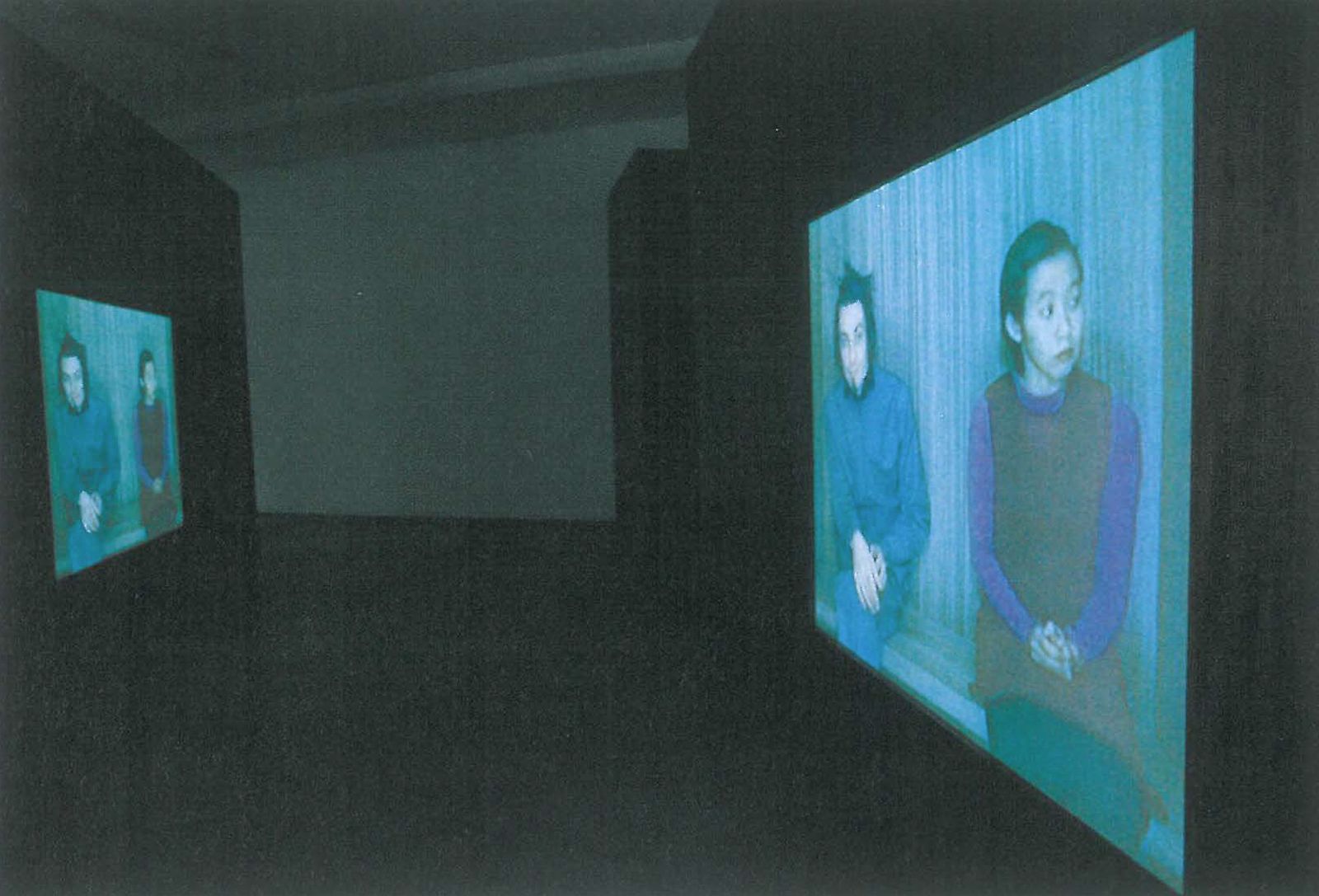

These concerns are evidenced in David Rosetzky's reflexive installation Custom Made. The back room of the Centre for Contemporary Photography becomes a space in which the spectator takes on roles from voyeurism and scopophilia to complicity and coercion. The installation situates a type of lobby (transitory place) by means of a wood-veneer corridor with both actual and projected benches. Real places - as in the form of benches for gallery spectators - are mirrored by video projected benches with 'spectators'. The projected 'portraits' contain seemingly endless variations of paired individuals either conducting a soliloquy-type monologue or 'just' waiting or watching. The space between the individuals is profoundly highlighted by the lack of contact and interaction. This lack begins in the way in which the individuals seem to be unable or unwilling to participant in their temporal neighbour's conversation. Within a couple of minutes it becomes apparent that Rosetzky's pairings were indeed shot 'individually' as one sitter fades into another's position. The projected spectators merge into moments and memory traces of actual gallery spectators.

As a spectator, the installation is both intimate and alienating. It evokes that feeling of walking along suburban streets viewing the anonymous occupants through various windows and wondering about the unknown lives and identities. To use the cliche 'to stand in someone's' shoes', Rosetzky's individual 'subjects' become spectatorial subjects open to interpretation and identification. Language becomes a distant friend of communication.

The various 'portraits' situate the problems of language and representation and hence the gallery spectator becomes simultaneously the active participant and the passive recipient. The gallery spectator, given the apparent role of 'watching' soon finds the role inherently plagued with the politics of being observed. The longer you 'watch' the various characters and narrations, the more you become part of 'being watched'. The complicity of 'just' observing becomes complex. Suddenly the viewer must rethink their biases and roles to the point that it is the gallery spectator, rather than Rosetzky's 'types', which come under inspection and reconsideration. The art audience becomes the 'subject' for portraiture; the 'act' of watching infuses the politics of being watched. A mode of reflection becomes a series of reflexive takes and double takes.

Rosetzky's 'portraiture' resists stereotyping of contemporary 'types' and contexts; it cleverly positions the spectator as an unfamiliar tourist attempting some grasp at anthropological self-reflexivity. The portraits are left open to the spectator - an arbitrary moment in someone else's temporality - and hence the role of the spectator is thrown into a series of active modes. Unlike the subtle overhearing of conversations on public transport, Rosetzky's characters convincingly feign an engagement as they look into the lens of the camera now occupied by the sitting spectator.

Custom Made is so persuasive; Rosetzky's characters become our characters. Their displacement and stories become our narrations and even our responsibility. The installation positions the spectator in between a cinema and a television context. The darkness and anonymity of the cinema is blurred into the intimacy and familiarity of television. The use of 'direct address' (direct eye contact) so often associated with television modes is employed with filmic non-distraction. Rosetzky's installation transforms the gallery space into a contemporary fusion between the private TV viewing and public film cinema. In this in-between space and place the spectator is positioned through various modes of viewing and identification. The trivial is mixed with the sublime; the local is also the global.

Rosetzky's characters range in age, gender and sexuality. Their concerns are specific and yet within the fading and repositioning, their conversations become recontextualised. In playing with both specificity and a kind of universality as situated by language and communication, they tie together seemingly different and arbitrary experiences. Avoiding the tendency to generalise and stereotype, Custom Made demonstrates diverse modes for thinking about contemporary identity and roles for spectatorship.