There is something almost reassuring about the 12th Biennale of Sydney now drawing to close in various venues across the city. It is as though all the angst that surrounded many of the recent exhibitions has dissolved, all the difficulties of staging overcome, all hostilities between past participants are over - now is the time to relax. This is in short a Biennale of Reconciliation. It taps into the sentiment that caused approximately 200,000 people to cross the Sydney Harbour Bridge a week after the opening - reconciling black with white, past with present, avant garde with mainstream.

This is an exhibition of self-conscious generosity, accommodating a range of living cultures along with the new. This is the fourth Biennale overseen by Nick Waterlow, who can now surely lay claim to being Sydney's contemporary art master. There may have been others involved in the selection process, but in its all-embracing nature, this is very much Waterlow's show.

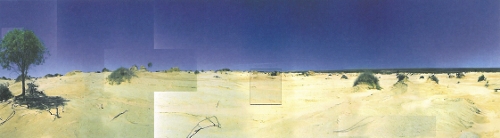

There is a recognition of spiritual and contemplative qualities - in work by John Mawurndjul, Rosalie Gascoigne, and Yoko Ono. There is also a strong argument for the validity of an Australian cultural experience. We are spared the travesty of Lynne Cooke's Biennale of four years ago when she effectively transplanted an exhibition from New York's DIA Center.

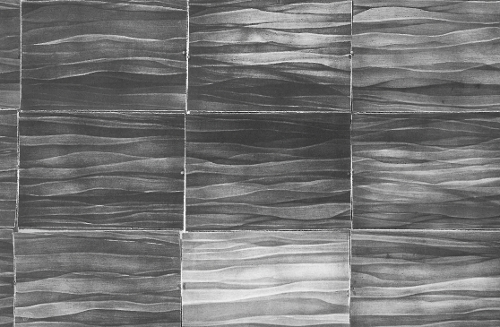

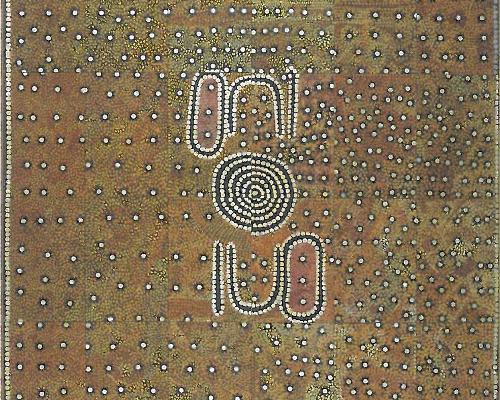

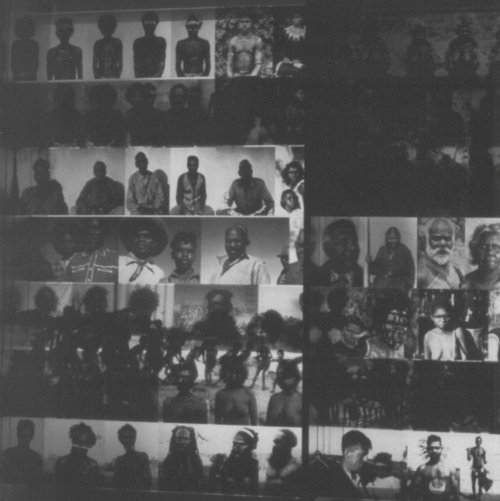

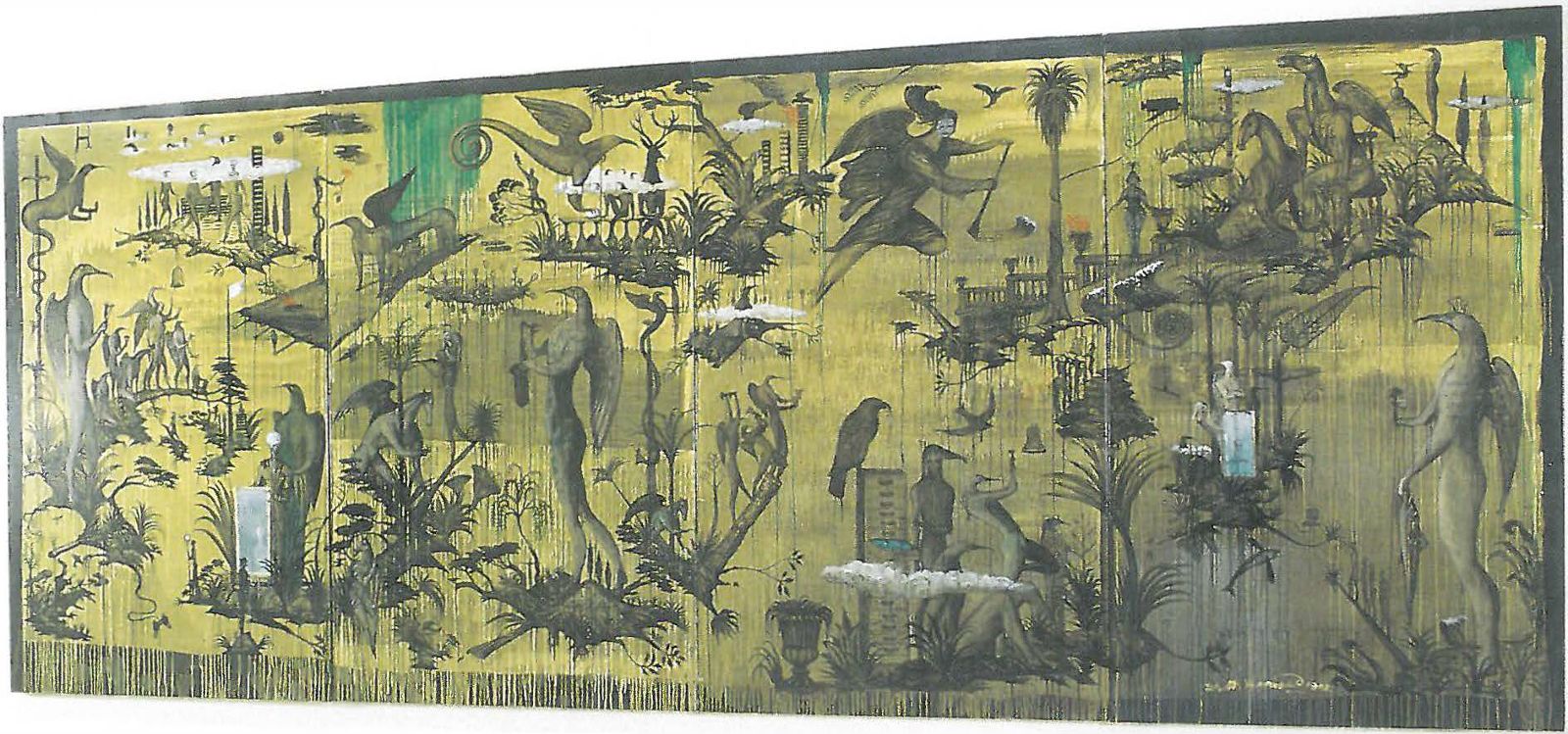

The most obvious Waterlow characteristic in this Biennale is a recognition of the importance of older artists and traditions outside the US Axis. In the 1988 Biennale Waterlow made the inspired choice of commissioning the Ramingining artists to create their Aboriginal Memorial, a commemoration of 200 years of survival. Since then it has been hard to imagine Australian art without a strong dose of the spiritual values and timeless traditions of the north. So now the visitor to the MCA walks past Andreas Gursky's giant formal photographs to the hand made inspirations of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, John Mawurndjul and the Maningrida sculptors.

The question then is - which is new? What is modern? For although the Aboriginal works draw on the oldest cultural traditions that the world can imagine, they are fresh. And Gursky, the modern western artist, is effectively reworking ideas displayed in Sydney only four years ago.

For the informed observer there is much that is pleasurable about this Biennale, but it is not the pleasure of being stimulated by the new. Rather it is the pleasure of reassurance, like putting on last season's clothes and finding they are still good enough to wear. The dominant feeling is mellow, not fresh.

Those who like their art to challenge are severely disappointed. Yet who are we to always demand the new, to insist on fresh visual flesh for our critical appetite?

One of the current debates on the nature of contemporary art spaces is how to make them palatable, how to make hoi poloi want to come inside. In this at least Waterlow et al have been spectacularly successful. Never has the MCA looked so enticing, never have so many Sunday crowds strolled through, looking at art for pleasure. It is not just that this Biennale is free (although that certainly does help). It is that the exhibits have been placed to both tantalise and intrigue.

Viewers wander, almost by accident into Mariko Mori's giant photographs, and sentimentalists are transported to a place that is a cross between the set for an old episode of Dr Who and Magic Monkey. Media-savvy cynics may comment on the use of Photoshop and large scale imaging facilities, but it sets the mood for something sweet with new age connotations.

There is a similar lollipop spirituality in Yayoi Kusama's Infinity Mirror Room, which entices the most hostile conservative into an acceptance of recent art as something light, bright, and vaguely intellectual. I don't know that these are the strongest works in the exhibition, but they do serve to bridge the gap between the avant garde and popular entertainment. Bruce Nauman's amusing video, No, No, New Museum, also fits into this category. It has another claim to fame - the very same work was exhibited in Rene Block's 1990 exhibition. Indeed it could be argued this Biennale is almost an argument against new art. Sanggawa's paintings were in a previous Asia-Pacific Triennial, Mike Parr is yet again a bride, Bill Henson, Gerhard Richter, Gordon Bennett - none is new.

Yet the exhibition does not feel tired, as it ought with so much old art. There is a freshness to the display and it is worth reminding people of the shared sensibility of Ken Unsworth and Louise Bourgeois.

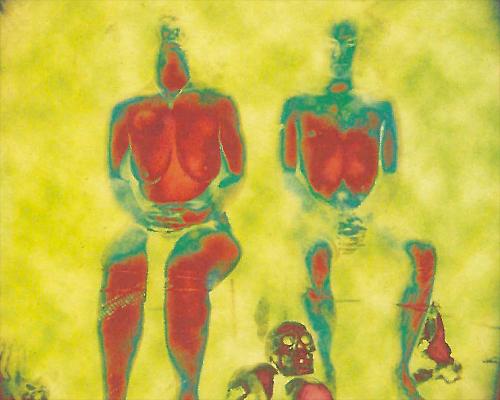

Because the Biennale has spread its net so wide, it is possible to see how and why certain works were chosen for particular venues. The MCA is the international showcase. It has the stars and the newer heroes. Here is Seydou Keita celebrating life in Mali, and Pipilotti Rist showing sensual pleasure with a pop-like bounce. There is Adriana Vareja, disembowelling painted terracotta for viscereal pleasure.

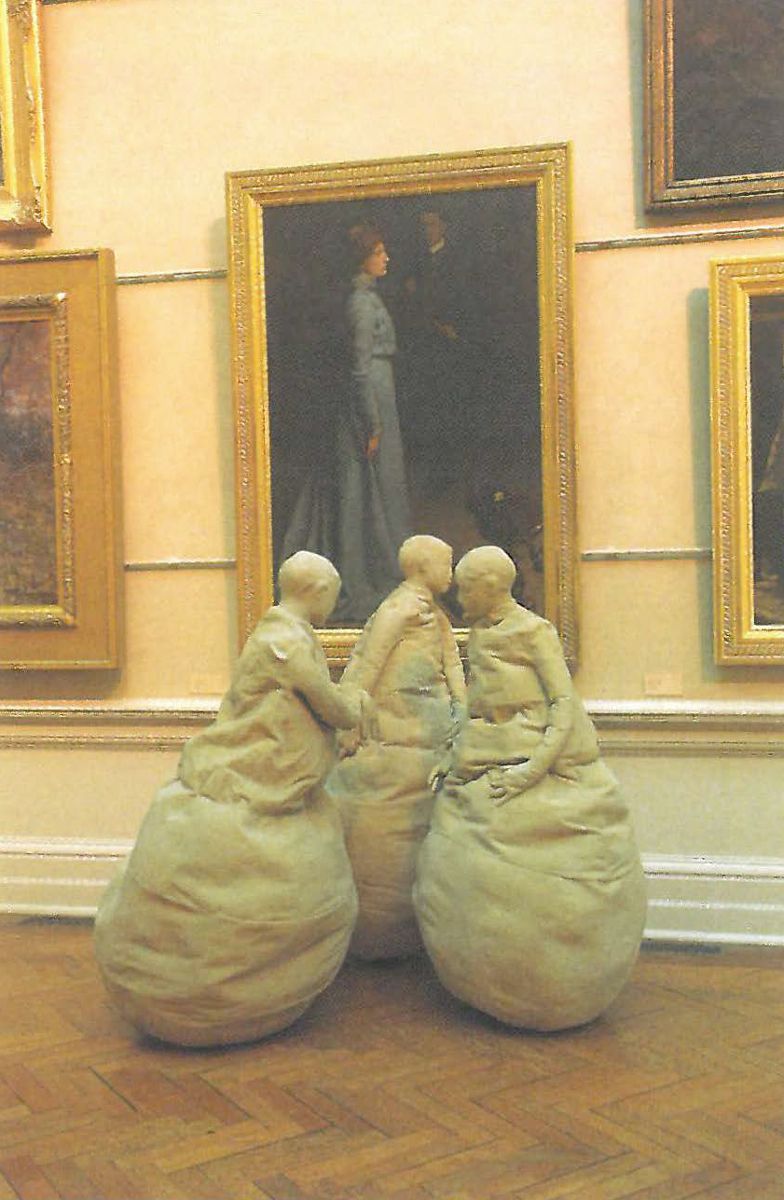

The Art Gallery of New South Wales is more conservative - and at the same time more popularist. They have Yoko Ono to draw the crowds, Juan Munoz to cheer up the 19th century courts, Xu Bing's amazing window, and installations of work by Ken Unsworth - well known as a veteran of the Biennale scene. Tracy Moffatt's work was easily the most popular of the AGNSW installations. Each time I visited the gallery a crowd was gathered to admire the wit of her video, Artist, a scissors and paste spoof of the filmic tradition. It was only after smiling at her swift juxtaposition of old film clips that the viewers turn to classic Moffatt - the photographs from Scarred for Life. This may be well known to anyone with a passing knowledge of Australian art, but it was new to many at the AGNSW.

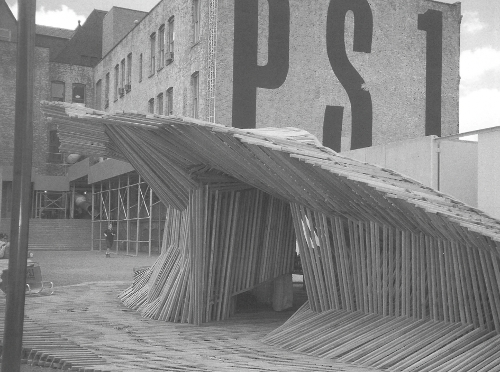

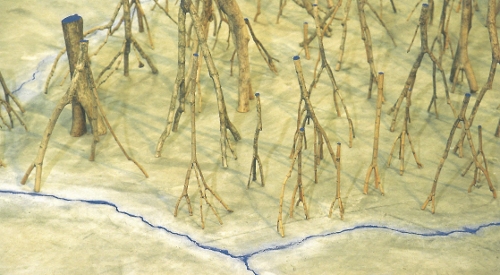

Not everything in the Biennale is as polished as this. The raw finishes of Artspace created an appropriate venue for Martin Kippenberger's wooden pills in a birch forest.

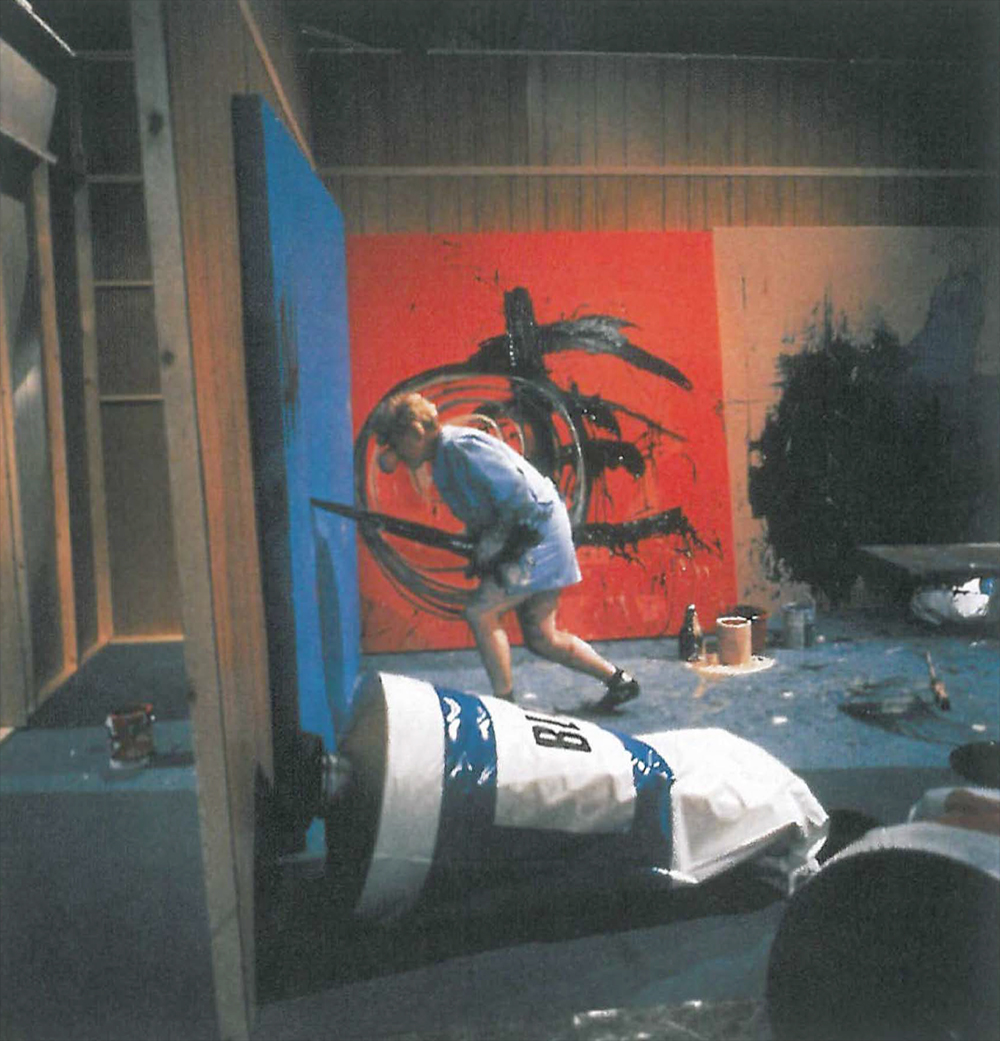

Artspace also saw a commentary on the often unstated realities of international arts festivals - a record of the damage to Paul McCarthy's installation Painter. Bearing in mind that McCarthy's work is so deliberately iconoclastic, is seems odd to read blown-up official commentaries on poorly packed work, all written in the lethal language of bureaucracy. The reason for the giant angry memos is that the artist chose to celebrate the damage as process, rather than have his work repaired. So in Sydney another old (1995) work is made new through destruction.