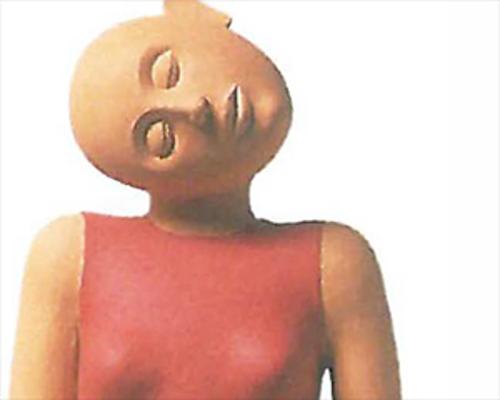

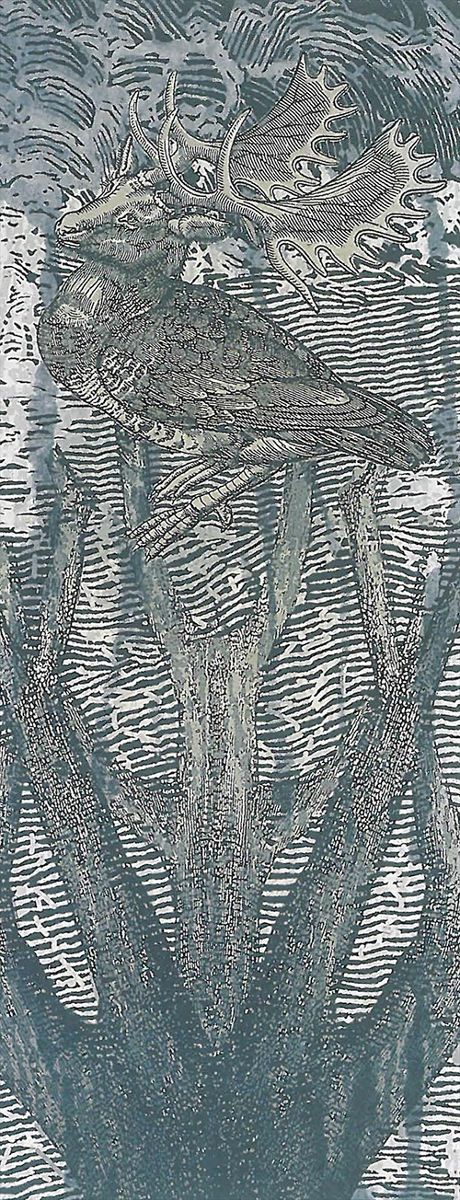

Precariously perched high on the bare branches of a mutilated tree a strange bird flaunts its fully-grown antlers. An amalgamation of a plump pigeon and a deer, this bird is one of a menagerie of bizarre creatures depicted by Milan Milojevic in his installation of ink-jet prints and platypus remains crowded into the Zoology Room of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Amid the clutter of stuffed Tasmanian wildlife the bird's mismatched features provoke the viewer to question what wild niche might have enabled it to evolve and what quirky biological imperatives could drive it to defy gravity in the face of a brooding storm. The desire, perhaps, to attract the small dull females of the species with its doe eyes and the pink hue of its antlers which will be shed at the end of the mating season if not accidentally ripped off while flying through the tree tops.

Influenced by the cultural and geographical displacement of his family from Europe to Australia, Milojevic, a first-generation Australian born of German and Yugoslav parents, uses the idea of the hybrid creature as a metaphor to explore issues of dislocation and identity. The juxtaposition of incompatible body parts such as wings and fishtails suggest the awkwardness of fitting into an unfamiliar environment and the contortions made by individuals to adapt to change and forge a new identity.

Among the strange beasts depicted by Milojevic in his prints are an ungainly fish with wings and claws gasping for breath; a foetus gestating in a hairy pod attached to a lily by a fleshy umbilical cord; a lamb-like thing called a Barometz which regenerates when it is eaten; a confused two-headed boar and a pair of Kilkenny cats which according to Borges "got into raging quarrels and devoured each other, leaving behind no more than their tails." In the midst of these imaginary animals Milojevic has included a platypus.

Apart from the platypus, these creatures relate to those compiled in alphabetical order in The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorges Lois Borges. Milojevic has created the hybrid beasts by scanning and collaging sixteenth century woodcut illustrations from Konrad Gestner's Historia Animalium. Disturbingly, much of the Tasmanian wildlife preserved and exhibited in the context of the Zoology Room seem as implausible as those documented by Borges.

Below the prints, in a wood and glass curio-cabinet that could easily be mistaken for part of the permanent collection, a long-dead mangy platypus lies on crimson satin. Beside the body with its leathery duckbill and decaying webfeet, there are odd white skulls, platypus eggs, a small pelt and small cardboard specimen boxes opened to reveal fragile bones nestled in tissue paper. Even though each skeleton is labelled to indicate the date and place that it was collected, far from familiarising the viewer with the animal's nature the display leaves one with a sense that it is an inexplicable and alien curiosity.

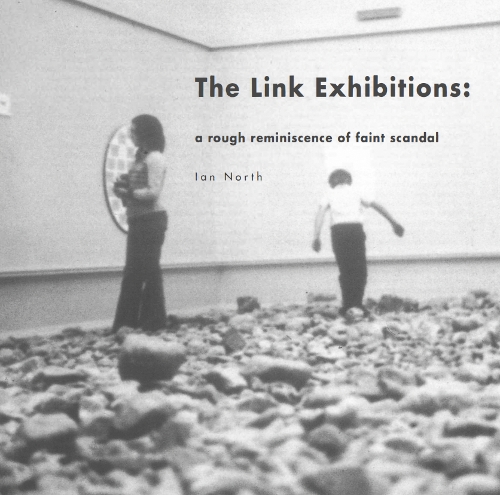

Index of Possibilities is the sixth of an ongoing series of projects titled Interventions at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. In each of these projects an artist is given the opportunity to create and install work in relation to one of the museum's collections. The juxtaposition of contemporary artwork with the museum's permanent displays, some of which generations of Tasmanians have visited as children, invites a dynamic engagement.

Notions of identity and dislocation explored by Milojevic in Index of Possibilities resonate in the Zoology Room. Dusty stuffed animals, specimen bottles and antiquated dioramas reveal an unresolved alienation from the Tasmanian wilderness. Like narwhal horns, which in the middle ages provided tangible evidence for the existence of unicorns and prevented poisoning, the Zoology Room presents each of these animals as mysterious and other.

Unintentionally macabre, the body of a platypus is fixed prone against a wall, its fur patchy and thin from the petting of delighted children. Glassy-eyed snakes are lined up in rows, a wombat is frozen in a plaster hollow and a potoroo, kangaroo and a couple of wallabies are propped together in an awkwardly animated death on a hillock tufted with dead grass.

As Borges' compilation attests, mythical animals have often been used to speak of dislocation. Characterised by its dog-like head, zigzag tiger stripes and a pouch to nurture its young, a ragged Thylacine haunts a glassed-in alcove in the Zoology Room. Presumed extinct despite frequent claims of sightings and on the eve of a resurrection through cloning, this musty remnant of an animal, as poignantly as Milojevic's mythical hybrid beasts provokes a myriad of questions about identity and dislocation.