Examining this exhibition and listening to the papers at the Symposium of the same name I was unable, despite the many diversions, arguments and blandishments from all directions, to escape the conclusion that almost all of the designers involved seem to want to be sculptors.

I am as partial as the next person to an elegant and sensuous object, but am handicapped by a deeply unfashionable belief that if objects of everyday use (furniture, household items etc) are to be a cut above the rest they should be innovative in design, utilitarian, readily available to the public and within reach of an average budget, should not impact negatively upon the environment and they should look and feel marvellous. Everything else is either just an average object (boring, hideous or just OK), a toy for the wealthy or a work of art.

Australia is not the only society in the world which does not support these criteria in its mass-produced goods; moreover we are not well situated when it comes to manufacturing. Neither, according to Catherine McDermott, a keynote speaker from the UK, is her country - any more. We have a worse than average relationship between our designers and our manufacturers, and the historical reasons for this are too many and too depressing to relate here.

What was interesting about the papers at the Symposium was a sense of optimism which was occasioned by little parcels of good news. The outlook is no longer necessarily one where designers work in rarified surroundings honing the perfect piece of plywood while manufacturers in the western suburbs staple MDF together. A middle ground is slowly but surely emerging, and wouldn't you know it, it's all thanks to technology. Just as digital video now gives everyone the ability to edit a movie, so computers, in a range of different ways, offer designers the chance to produce serial objects in a limited way which can be offered to the market outside an art or design gallery to purchasers other than museums.

This is a gross simplification of the situation, but it is true that the new-ish system of rapid prototyping has allowed people working in ceramics, plastics, and various other materials to go from computer screen to plasma prototype and then to limited production without calling in the big guns. As John Ullinger told us, behind the facades of the darling old 19th century Potteries of the Midlands in the UK are rooms full of computers exuding serious grunt. The prohibitive expense of rapid prototyping when it first arrived about five years ago is starting to recede, and the effect is starting to be felt at the level of designer-maker. Marc Newson was even able to go from his computer-generated design directly to injection moulded polyethylene for his sexy and functional dish rack Dish Doctor (1997) without a physical prototype. Numerically controlled cutters can deal with a vast range of materials from timber to steel to fabrics, and again the new tools allow the perfection of a machine-made item without the investment required by mass-production.

It was interesting to hear keynote speaker Paola Antonelli from New York talking about Mutant Materials, the first show she curated on taking up the position of Curator of Design at MOMA. Visitors were encouraged to touch the objects to get to know new materials, or materials which can now be used in new ways. Her mission at the museum is "to explain that design is an autonomous thing" and that it should not be compared to art. This is harder than it should be, as design seems to have been gobbled up by the insatiable maw of fashion; she was not alone in noting that "the magazines are the problem" with their 18 month product cycle from rapturous release to old hat.

Convenor Dr Robert Crocker reminded us about the familial structures in Italy by means of which the household name Italian design products come into being. These structures, and the black economy which goes with them, do not thrive in a regulated society like Australia (how would the average Italian small family firm deal with the GST?) Trained designers have typically been absent from these firms, with family members doing the designing with advice and product testing from other family members. In fact firms often went bankrupt when a designer moved in, with a dud product.

There were two subjects that were conspicuously absent from this otherwise wide ranging and stimulating collection of papers. One, curiously was the Olympic Games, which one would have expected to have been an employment and R&D opportunity for the community of designers, and the other, incredibly, was eco- or sustainable design.

Suzi Attiwill was to my knowledge the only speaker who addressed this subject at all, and she seemed to have trouble finding products to exemplify the concept. This can indicate one of three things - that Australian, and possibly global, designers have fully absorbed the lessons of eco-design and don't need to talk about them any more, 2 that Australian designers have put eco-design in the too-hard basket, or 3 that it has been totally eclipsed by the more powerful engine of 'the object of desire'. There was no talk of sustainably harvested timbers, recycled plastics, reusable items, an anti-obsolescence ethos... so one has to assume that option 1 does not apply. There was a lot of talk of 'creative' of 'nostalgia', of globalism, marketing and 'designer' items as an indicator of social status. There was breathless talk of new partnerships between designers and industry in Queensland, and a worrying account of a massive Centenary of Federation project by Craft Australia to create corporate merchandise for the National Gallery of Australia where tea sets and mirrors will emerge emblazoned with images from the collection (fancy a Blue Poles tea towel?)

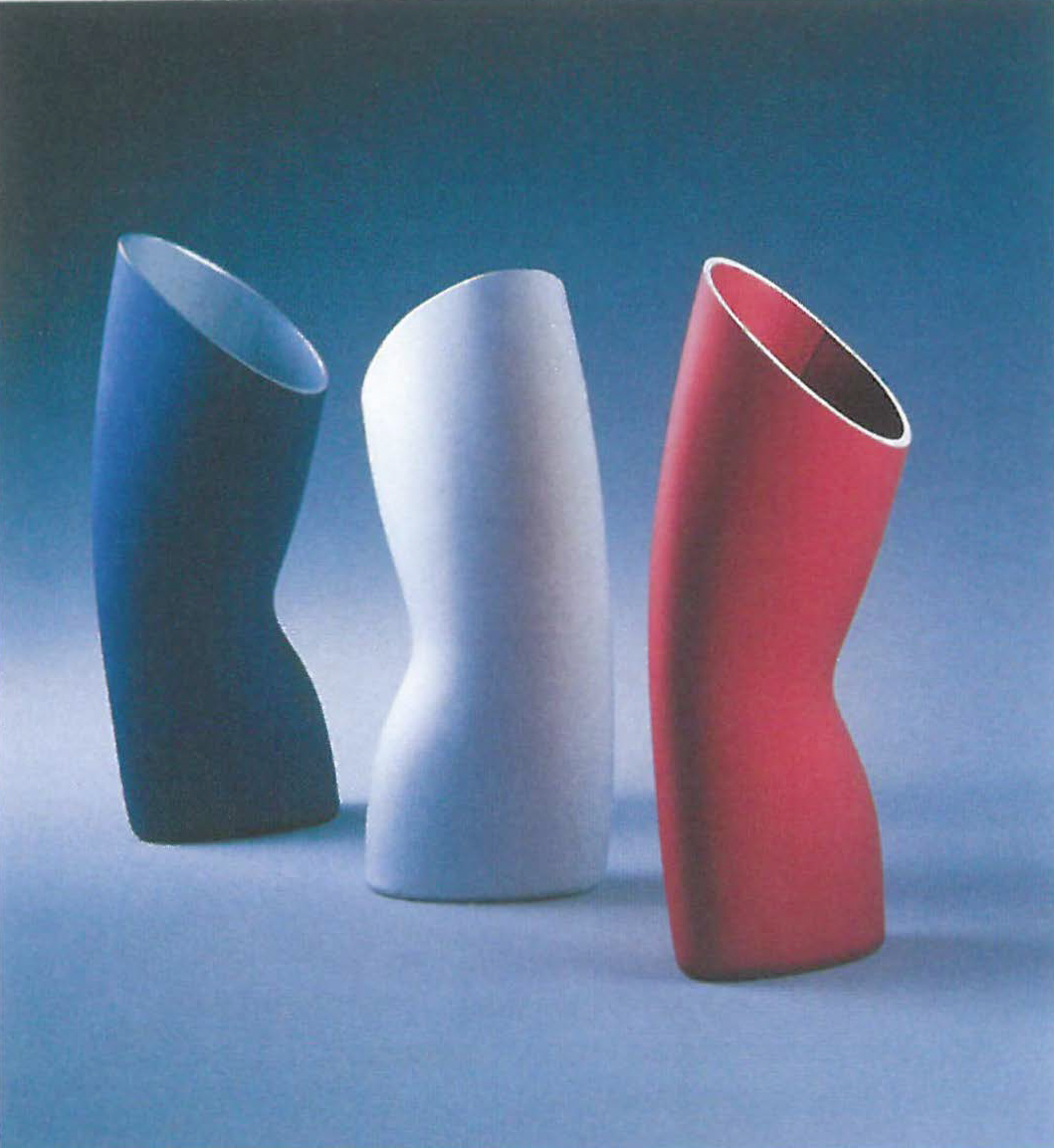

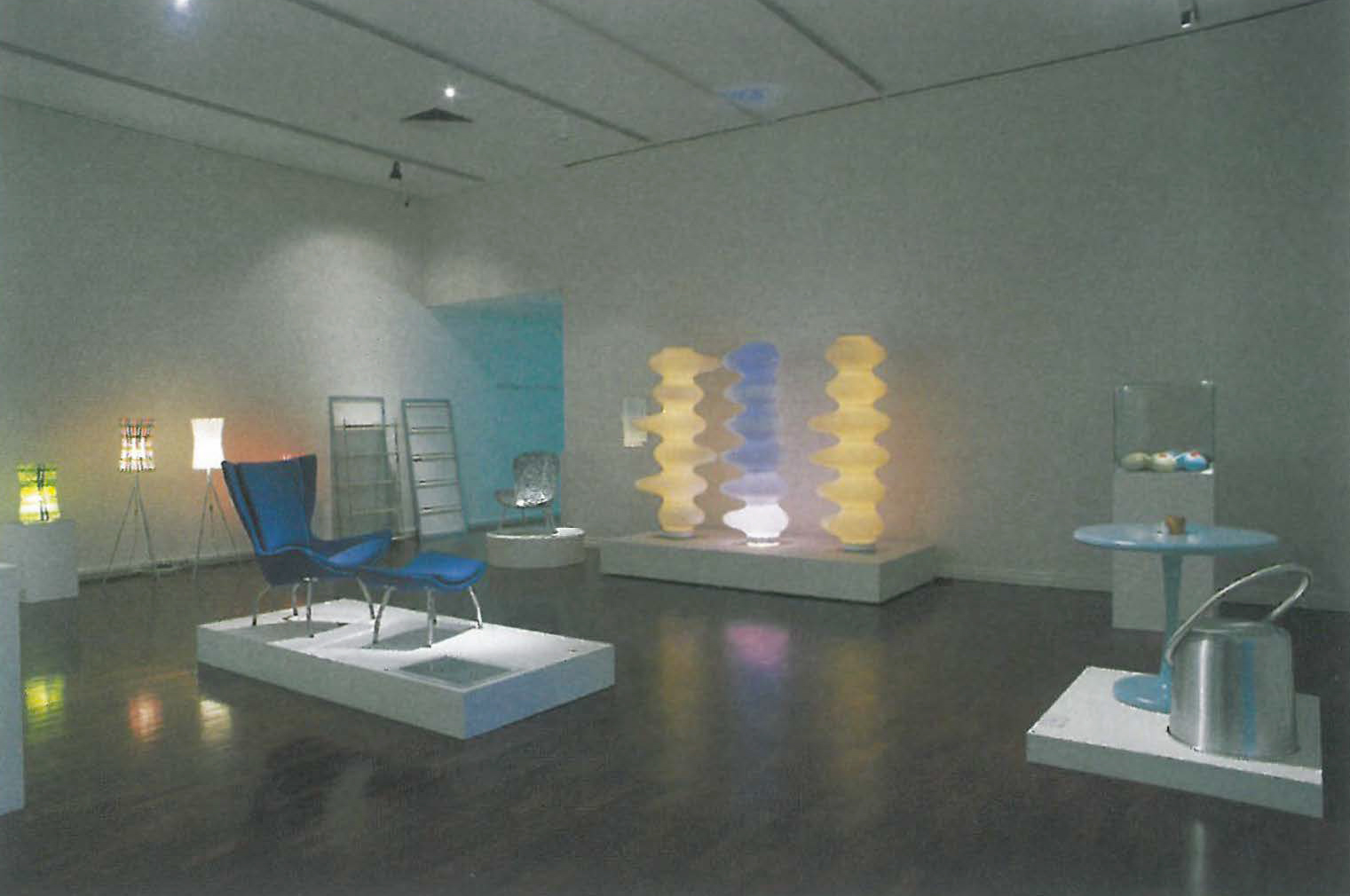

In the exhibition, a joint project of Craft South, Object- Australian Centre for Craft and Design, the JamFactory and the University of SA, the impression was of design aspiring to the condition of sculpture (visitors were not allowed to touch) - various attractive and desirable objects, some of which are in limited production, mainly out of small workshops, but few of which are outstanding works of design and some of which are plain gimmicky. The sublime lighting of Frank Bauer and the tables of Caroline Casey are exceptions, as well as the ingeniously made vases of Fink Design and the labour-intensive but clever fabric lamps of Ovo Design. It was encouraging to see Rivet's prototype chair in recycled plastic; the overall question of environmental impact becomes academic because of the limited production runs of all the products. The question of impact on mainstream design standards is one which remains to be seen.