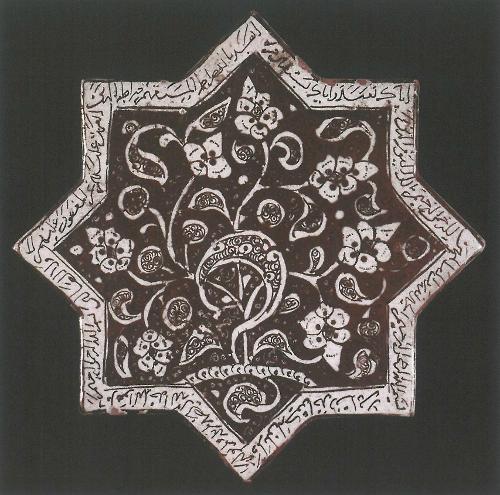

The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on

Nor all thy piety nor wit shall lure it back to cancel half a line

Nor all thy tears wash out a word of it.

- Rubayat of Omar Khayam

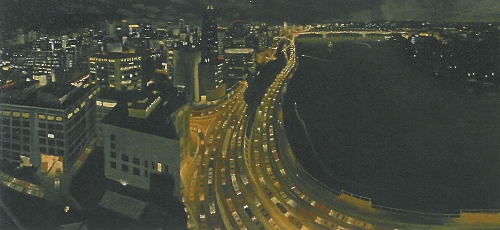

To gain access to the front room at Franz Ehmann's Soapbox during the week hours you have to ask for the key from Franz. The front room is a glass-windowed box with nothing between it and the roaring traffic of Brunswick Street but a narrow strip of pavement. On opening nights, though, the room's open for the duration, and in the almost unbearable heat of summer the crowds inevitably congregate here or in the tiny back courtyard that leads to the toilets. Bleak choices, you might think.

Bleakness has provided an influential leitmotif for attempts to define modern (and post-modern) life for the past century. But the locations to which this bleakness has been traced has shifted from landscapes to the urban environment.

In American Psycho Brett Easton Ellis mines the bleakness that lies deeper than the glossy veneer of what poses for contemporary American culture. This particular bleakness lies a long way from that which epitomised bleakness to the generation before my own: T. S. Eliot's The Wasteland carved out an empty soulless neverland that nevertheless echoes with the emptiness of God's retreat. Easton Ellis' contemporary mise en scene rings with no such yearnings. The smooth flawless high-sheen walls of his apartments and offices, bars and restaurants offer nothing but the hollow echoes of mindless banter. Easton-Ellis clads bleakness in custom-cut couture, carefully selected for the association that branding brings. Easton Ellis' moral and ethical wasteland spares no remorse for the heart that has been cut out with a chain-saw when it can settle for style. If Eliot's wasteland evokes the grainy horrors of the Somme and Ypres, then Easton Ellis' resonate with the ghastly clichés of the corporate world.

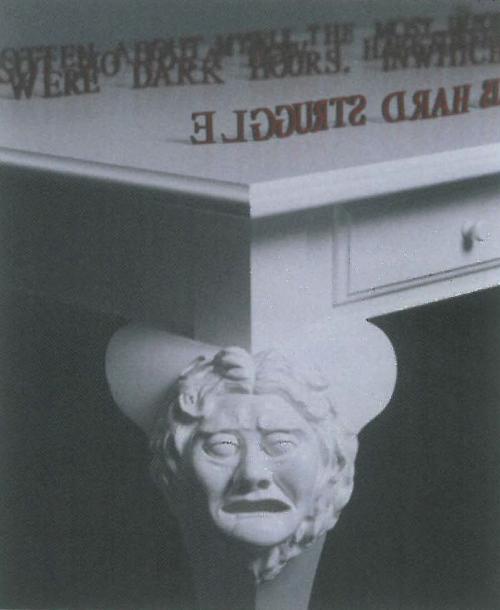

The installation of Christian Flynn sifts through more familiar and domestic representations of maleness – he selects the genteel mementoes of another era and re-brands them – literally – with chilling reminders that the tools of old men carry traces of bitterness and bleakness that leach into the present.

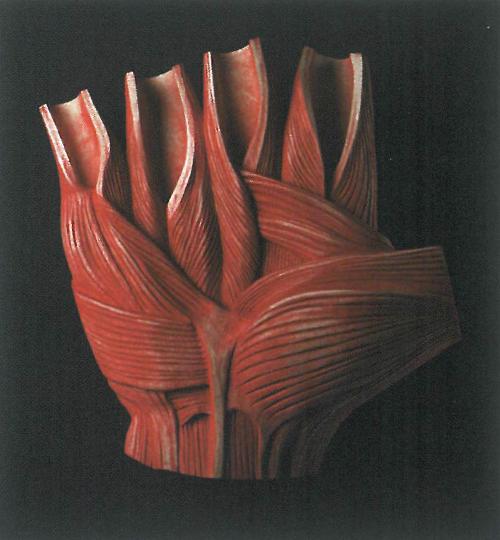

I visited Christian Flynn's exhibition on a weekday. In order to see into the unlit room you have to peer closely into the window. Mere metres behind your back the scream of traffic shaves against the pavement. The prospect of contemplation has been ground to a knife wedge of possibility by the friction of daily life. Inside, the room bears traces of its former uses – a sink, domestic proportions. An axe has been positioned against the wall opposite, and along the far wall a series of small watercolours. The shapes they depict are amorphous, becoming. They seem like fragile attempts to create form. They seem threatened by the objects assembled in the room.

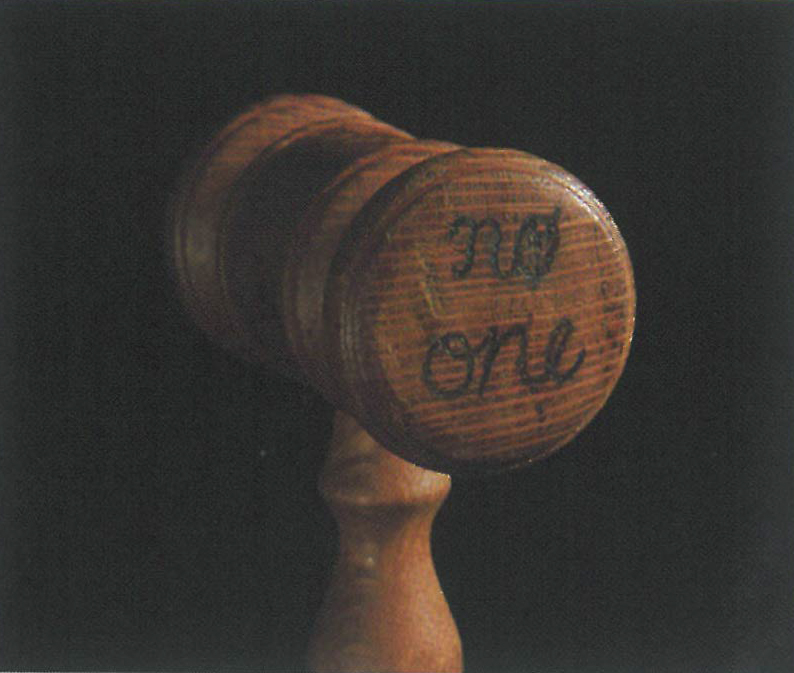

Against the window, a table has been pushed. On it lies a selection of implements - a gavel, a cheese board, a small axe, a mallet, a plane, a spirit level. Such objects, perhaps gleaned from collector's shops and antique stores, are among that kind of bric-a-brac that accrues value in proportion to the sense in which they seem to evoke another time. Other values. Their wooden surfaces have been worn into a subtle patina through years of use. They seem quaint. Olde-worlde. The kind of genteel stuff that reeks of an era when people had time to perform slow, more meditative tasks. A time that seemed a world away from the pace of the traffic beyond the window.

Once inside, though, the objects bear evidence of having been tattooed with script. A number of fonts and styles, but all writ with the kind of burning and scarring that a soldering iron leaves. And the words and phrases that are etched into the surface reclaim these objects back from the dim mists of sentiment into a legacy that has continued unbroken from generation to generation.

On the axe - 'The blood of the other, of another, fills my shoes and the light of a righteous God fills my heart.'

On the gavel – 'Spare No-one.'

And on the breadboard – 'The sins of grand old men stain long and fast. The reek of that old blood cannot be put down. Its mind will pierce you and poison. Do not doubt the potency of this.'

And so on. From object to object.

Like the words in the epic Persian poem Rubayat of Omar Khayam, the words seemed to momentarily hang in the air, hover with portent, and then vanish. Outside the world's traffic flowed on and the airwaves and tabloids and screens pulsated endlessly with justifications for old men's wars.