The six Melbourne-based artists featured in NEW03 all have an existing profile and exhibition history – none could be thought of as new, as such. But then neither is this claim made for them – in the fine print of the gallery info they are referred to (new term) as 'emerged' artists. The NEW of the title ostensibly refers merely to the fact that the exhibition is of new works commissioned by ACCA from these artists.

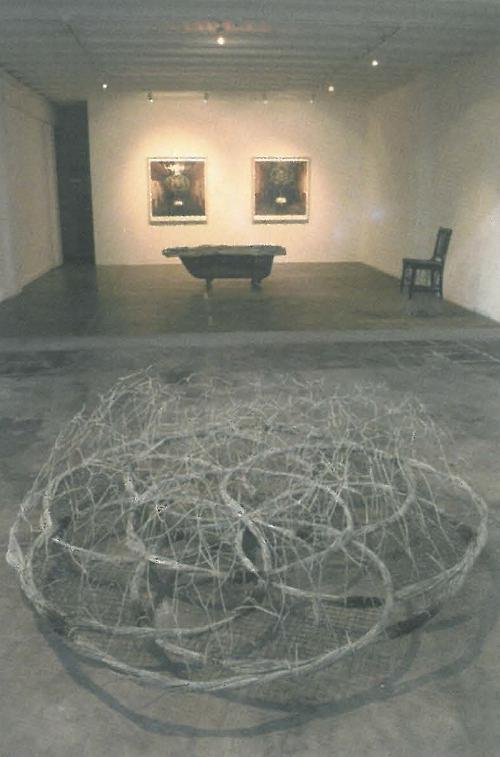

ACCA is not new either. But, this is the new ACCA. The domestic scale of the cottage in the gardens has been replaced by an industrial hangar of rust coated rolled steel designed by Wood / Marsh Architects, with interior spaces liberated (in height mainly) for flexible display. Opening towards the end of last year, under the direction of a new team (Artistic Director Juliana Engberg and Executive Director Kay Campbell), the character of ACCA is yet to be established. NEW03 is, it is promised, the first edition of an annual fixture in their program.

The titling of this exhibition series (making most sense in terms of marketing) tells us something about how the new ACCA sees its role in the contemporary art scene in Melbourne and nationally. It suggests the broadening of the audience it hopes to attract – acting as a first entry point to the contemporary scene, capturing an audience for whom these artists would be new rather than as in the past, arguably, addressing itself primarily to an audience in the know. This positions ACCA as sitting atop and being fed by the existing network of gallery spaces (artist-run, government funded, commercial). As a corollary the rationale of the show elaborates a vision for ACCA providing a new institutional depth to the contemporary scene.

In contrast to the MCA's equivalent Primavera – a curator-driven summary of a new tendency among emerging artists – the formula for NEW of commissioning works from the recently 'emerged', can be seen as an attempt at matching and sharing resources (the expansive promise of its new facilities), with the aspirations and experience of artists, giving them the opportunity to do something of a more significant scale and scope than might have usually come their way at this point. The goal is to nurture a 'new maturity'. And that's not a bad thing. For the most part, the artists in the exhibition have met the challenge with works that are substantial, ably 'filling' the formal and conceptual space given to them.

However, personally, I am still immaturely fixated on the new. While no argument is made in the catalogue for an overall linking of the artists around any particular thematic (let alone what could be considered 'new' about their work), there is a tantalising confluence of interests amongst at least four of the artists. I'm prepared to stick my neck out, 'relationship' if not new as such, is the new thing.

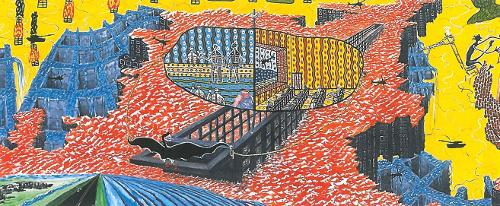

Andrew McQualter's illustrational drawings attached to pin boards, outline experiments in creative collaboration – two people make sculpture out of the one piece of playdoh; two people design the floor plan for a shared living and working space, both holding the same pencil. How to negotiate being in relationship with others is part of the process as well as the problem McQualter addresses in his work.

In David Rosetzky's multi-screen video installation Untouchable the audience simultaneously watches three different domestic interior scenes each with two inhabitants, implying a relationship between them. The narratives the characters tell are about the inability to communicate with the other, and the entanglement of disaffection produced by proximity (R.D. Laing's Knots again.) Time spent with the work reveals the narratives you thought were owned or belonged to one character are shared by all, repeated in sequence. The idea of genuine emotional intimacy, and the genuinely expressive artwork is similarly undercut by the formalism of this equation.

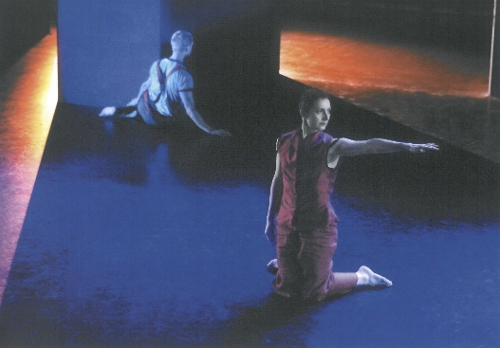

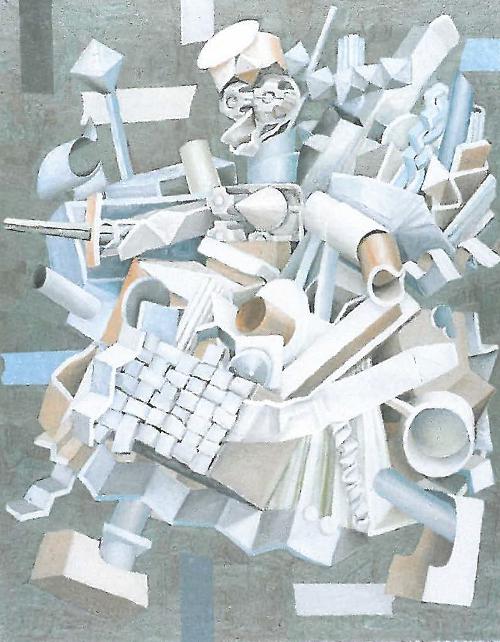

Even Daniel von Sturmer's elegant work, most straightforwardly offering the viewer a captivating aesthetic experience, ponders this realm. On a raised and angled 'floor' five small screens display video footage recording pseudo perceptual experiments, such as those conducted in a psychologist's examination to assess our hold on the logic of reality. The props are low end: rolls of Sellotape, a rubberband. Our understanding of what is happening in each case, our reading of the relationships of the objects in the scene – which way is up, whether the variable is size or distance – are reliant on our position in relationship to the action, a factor abstracted by the disjunction between the time and space of the video footage and our own.

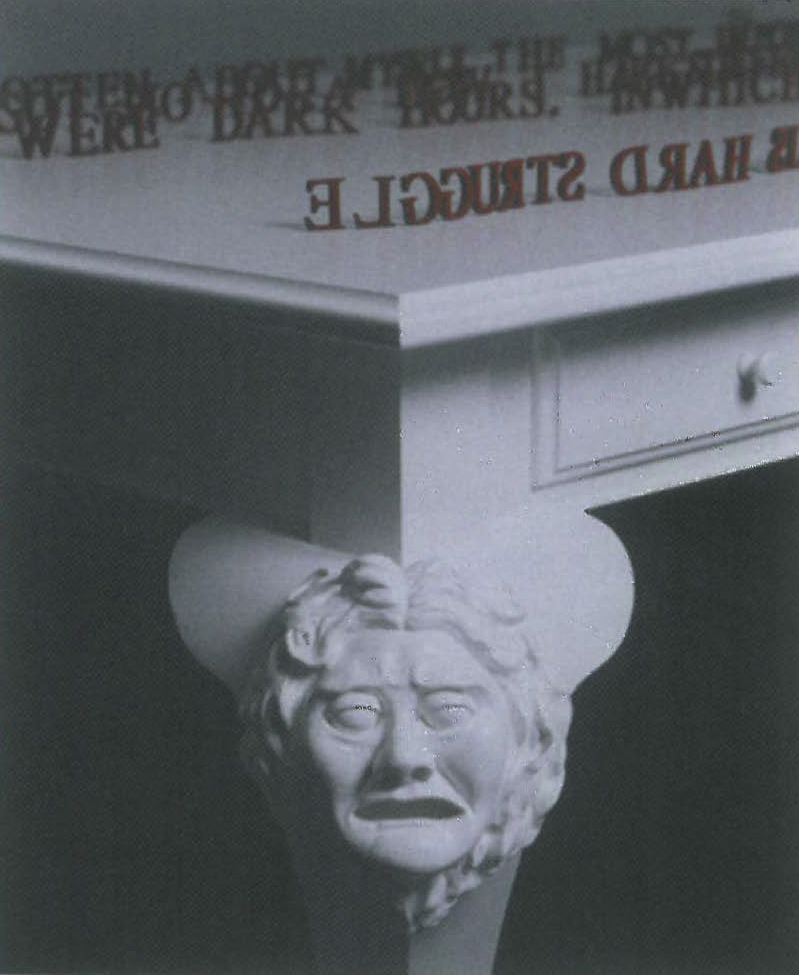

Emily Floyd's work comes closest to the bone in dealing with the relationship between audience and artwork, spelling out the needs and expectations, anxiety and aggression projected in that exchange. Letters covered in crimson red flock deliver the lines in the drama, from atop grand bureau tables finished in white lacquer, with bowed rococo legs, on each a masked face in a Mannerist 'theatrical' grimace. Walking along, the viewer reads the tale of woe: 'I'll never tell you anything.' 'By the time you come here twice or thrice you'll hardly notice how oppressive it is in here.' 'For whom do I carry on this hard struggle?' Of course, nothing is ever new.