Duck Island in South Australia is home to James Darling and Lesley Forwood, environmentalists and farmers of 16,500 acres of which half is bush. They are also consummate artists, travelling the world to present their installations whilst working closely with one another and with the flux and flow of their place and time.

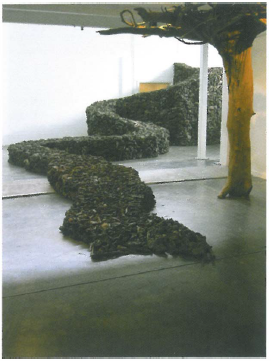

“Nature is not a background” according to Darling as he and Forwood dumped something like twelve tonnes of dead vegetation in a gallery to put nature firmly to the fore.

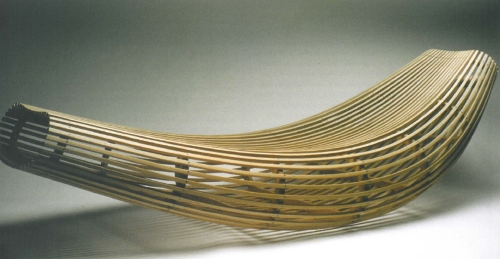

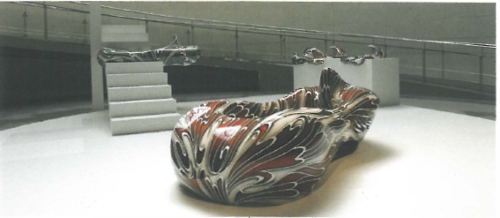

Making one from the many, by stacking and interlocking thousands of mallee roots, they set out to express the big picture of ecological processes with a massive, sinuous sculpture obvious in its form, elegantly subtle in its intent and as intriguing as a giant jigsaw in which each piece has its own fascinating form, texture and pattern. The self-supporting construction begged questions about climate, land use and even politics – at the time these mallees were growing land clearance was mandated. In 1980 Darling lost 4,000 acres to the government for not having cleared enough!

Evolution of the mallee root as an artistic medium began when Darling and Forwood were clearing roots and seeking economical methods to deal with the massive volumes involved. Initially they made ad hoc piles, then gave the piles ‘edges’, then corners, and so on. Their technique is now well honed and from the naturally gnarly lumps of root they fashion waves, walls, curves or cubes (eg. the Thinking Beyond the Square installation at the Wilderness School, Adelaide, 2004).

An active writer and advocate for better land management, Darling’s fame as an installation artist began with his Mallee Fowl Nest series in which carefully concocted piles of interlocking mallee roots replicated the scale and form of those remarkable artefacts of avian habitat.

Comparisons with Andy Goldsworthy are hard to avoid. Neither Goldsworthy's work nor that of Darling and Forwood could have happened without a deep awareness and observation of nature and its processes and a preparedness to accept the properties of nature in its unwrought state.

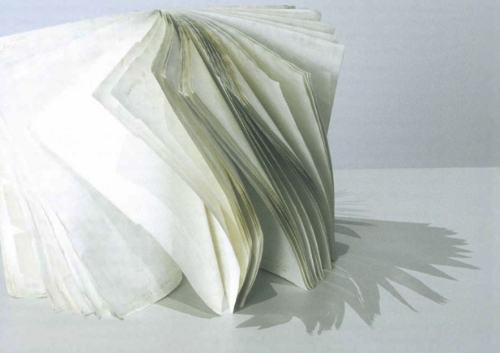

The Greenaway installation included an inverted gum tree that threatened to be extraneous to the winding stream of mallee. But looking closer, one’s attention was drawn to the whorls and winding tracks of the beetles, borers and ants integral to the life of this dead log. The wide root-spread told of salt pushed up by a high water table. In the artificial environment of an art gallery it provided a viewing of the mallee roots with a reminder of the original context.

“If every mallee root was a raindrop” says Darling, then what he and Forwood are doing is like “landscape management on the scale of a raindrop”, a sweet notion to remind us that water matters and “all land managers must work with the catchment”.

Darling calls himself a “failed poet” but drops carefully crafted one-liners into his conversation and clearly understands that his work with Forwood carries its own kind of poetic lyricism and strength. There is some “art” in which the effort to send a message drowns any aesthetic pleasure. Everyone Lives Downstream is not in that category. Here, the artists take the clunky worthiness of environmental conscience into the realm of very good art. They enable us to cherish some glimmer of hope that amidst the complexities of urban-industrial civilisation all ‘waste’ has a similar capacity to be re-evaluated and lyrically transformed as a link between the living world of nature and the habitat of the human spirit.

Their message is being well distributed. A container of roots has been travelling around Europe for several years with the artists creating new installations in venues like the Australian Embassy Gallery in Paris, ARCO in Madrid and the Pori Art Museum in Finland.

Darling emphasises that Forwood’s role is much more than that of “installation assistant”. Theirs is a work of collaboration that displays an intense, evolutionary consistency that well fits the idea of inter-relatedness. The powerful feeling of wholeness in their work is expressed via a medium of many separate elements, and like any good relationship it is not always possible to tell where the boundaries are, where one begins, and where another ends...