Does reality correspond to my experience of the world and how does it relate to the ways that I represent reality in order to think about it? These are questions traditionally posed by philosophy but which have in the twentieth century been increasingly asked by artists. Picasso asked these questions with regard to painting and Duchamp more radically with regards to the art object. As soon as we think we've got it figured out, our concept of reality changes as a result of advances in theoretical physics.

These are the conceptual issues at the heart of Christian de Vietri's show The Nature of Things. He takes banal everyday objects such a fridge, a gas bottle or a crowd control barrier and subverts them to produce mutations that play on and question their meanings, the status of their reality as image and their relationship to the way in which language also represents reality.

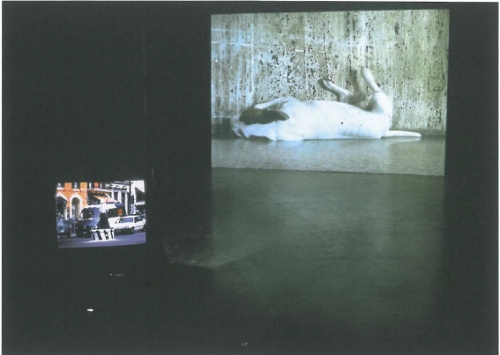

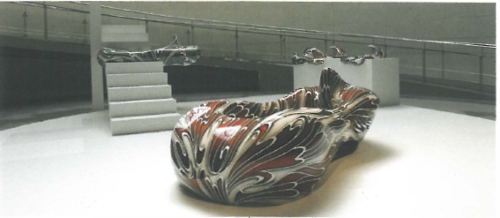

Two works are called Einstein's Refrigerator, 2nd law and 3rd law respectively. In the first one a white fridge has started to melt into a puddle as its increasing disorder erodes its individuality and it begins to merge with the rest of reality. In the second, the fridge is reduced to a white goods puddle with only its handles and General Electric nameplate giving a clue as to its former identity. Both works not only explore the energy relationships of systems, but are also metaphors for the living organism and for death. Life, like the refrigerator, is a system in which energy is expended to maintain the entropy of a body in a steady state. Death is a meltdown in which our physical body reverts to its former state of randomness. There is only one way in which this dissolution of physical individuality can be arrested. This is, according to the 3rd law of thermodynamics, when a temperature of absolute zero is reached.

The Road to Mont St Victoire is a photograph of the outline of the snow-clad mountain made so familiar to us by Cézanne's many studies of it. We take it for granted that the road is a metaphor for the journeys perhaps of art history or perhaps of the artist's own progress. However, closer inspection shows that we would be quite wrong to apply the usual trope to this image. It is in fact a photograph of the white road marking on the tarmac of an actual piece of road, which the heat of the sun has perhaps melted so that it has formed by chance, or by digital intervention, the familiar shape of the mountain. The image is the reverse of our expectations. This is no metaphor but an actual piece of road that leads to the famous mount. It is also a clever reversal of Cézanne's project, a re-inscription of the literal meaning he so firmly rejected.

Six Degrees of Separation is a series of six chromium stands on a red carpet that hold a crowd control barrier, the sort familiar to us in airports or banks. The first stand is firm and erect while each subsequent one becomes shorter and bends over more as if overcome by an increasing flaccidity. The work explores the complex of ideas around the whole power play involved in sexual relationships and in their shifting boundaries of intimacy and separation.

These qualities of witty reversals, punning and plays on meaning are typical of all the work in this show. Although his work operates entirely on a cerebral level, de Vietri has realised that more is needed than an aesthetic of ideas. His sense of intellectual fun is beautifully translated into visual form so that their conceptual elegance is mirrored by an equally stunning physical realisation. They become facts in the world of physical reality. It is this that makes his works so enjoyable.