In 2022, the Adelaide Film Festival made a callout for the first Expand Lab commission, bringing together intergenerational visual artists, filmmakers, producers, VR makers and performance artists. Allocated into groups through a series of social interactions and common interests, each creative pitch was developed and presented within only a week. Matthew Thorne, Emmaline Zanelli (both from South Australia) and Susan Norrie all shared a social or political interest in Olympic Dam, the state’s largest mine, its fly-in fly-out (FIFO) workforce and the purpose-built service town of Roxby Downs. Although the three artists eventually separated to make individual films, the contrast between each approach showcases the strength and distinction of their artistic voices. Their requests to film at Olympic Dam were repeatedly denied by the mine’s owners BHP—who bankroll the Tarnanthi Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at the Art Gallery of South Australia, just up the road from Samstag Museum. But this corporate refusal redirected the artists to alternative, wider approaches in documenting the impacts of one of the world’s biggest mining extraction sites of copper and uranium, with smaller deposits of gold and silver. What unfolds across a running time of just over two hours is a moving triptych, interconnected by shared concerns and practical constraints.

Screening upstairs at Samstag Museum [with Archie Moore’s roofless Dwelling (Adelaide Issue) (2024) visible from the mezzanine], each film is located in its own separate space; these viewing chambers are transformed into quasi-cinemas with long black sound baffling curtains and screens illuminating the darkness. The inevitable sound bleed between the works is a reminder that gallery spaces are not custom designed for cinema, but offer something of an in-between space.

In the first gallery, Matthew Thorne’s Extraction (2024) is a sombre and haunting look at the destruction of the land at Olympic Dam and surrounding areas narrated from an Indigenous perspective. Throughout the film, a woman’s voice is heard as if through a phone, floating over the arid landscape. The voice belongs to Kuyani woman Donna Waters, who Thorne met several years earlier on another project. Her disembodied speech guides us, confides in us and warns us. Waters tells us how her grandfather told her, 'you can look at the rocks, but don’t touch, don’t take them away'. The film functions through this ancestral wisdom by gathering information through careful observation during its 61-minute runtime. It’s a meditative yet conscious process of looking, scanning and gleaning the landscape: of what’s there, what used to be there and what might not be there in the near future.

The locations captured are the result of filming around restricted areas of BHP’s dams (Olympic Dam, Oak Dam and Carrapateena). Thorne and the crew travelled from Adelaide to the opal mining town of Andamooka, nearby Roxby Downs, 450 kms north to Coober Pedy, back down to Roxby and then north onto Borefield Road, where the water bores run to Olympic Dam. These areas are highly valuable culturally for First Nations peoples, and economically for mining. As Thorne reveals, ‘From what I keep being taught, all Country is sacred… all is specific… all is part of Story.’[1]

Conceptually, Thorne has been inspired by the films of Jonas Mekas, Derek Jarman and Chantal Akerman, where the 'extracted' voice becomes the guiding mantra.[2] In his previous films The sand that ate the sea (2020) (in collaboration with Derik Lynch) and Marungka tjalatjunu (Dipped in black) (2023), the journey through the remote parts of Country was about finding one’s spirituality and identity in the land. In Extraction the concerns are about protecting and preserving that spirit. Thorne says his original plans and preconceived ideas for this project fell away after he opened up to the work and listened to what the land was trying to say through Water’s voice. ‘This is my ancestors,’ she says as an image of a hefty opal boulder, shining with its iridescent colour, is inspected. Besides the hands that inspect, there are no other visible humans in sight.

As the filmic journey continues, Waters tells us how, when she was a kid, there were hot water springs—'bubblers'—that used to shoot water twenty metres into the air. Now the water levels are getting low. When she thinks of the mining companies planning to expand further into sacred sites like Lake Torrens, she laments ‘that would be the last straw. What will be left when this land is lost?’

Beneath the documentary-like surface of Thorne's film lies the land’s spirit and pain. As audiences, we feel it especially through a haunting soundscape. Dense sub-drones, harsh and violent clanging metal works and the low hum of the earth suggests the mine as an invisible entity in a horror film, grinding away as the town lives, wakes, works and sleeps nearby. This tension between productivity and people is threaded throughout. The tether fuelling the mine’s production is the bore water pipeline, drained directly from the Great Artesian Basin. This scene is the only shaky shot in an otherwise composed framing, followed by a sudden cut to an aerial view of Olympic Dam which reveals the vastness, destruction and monumental power that this mining production holds.

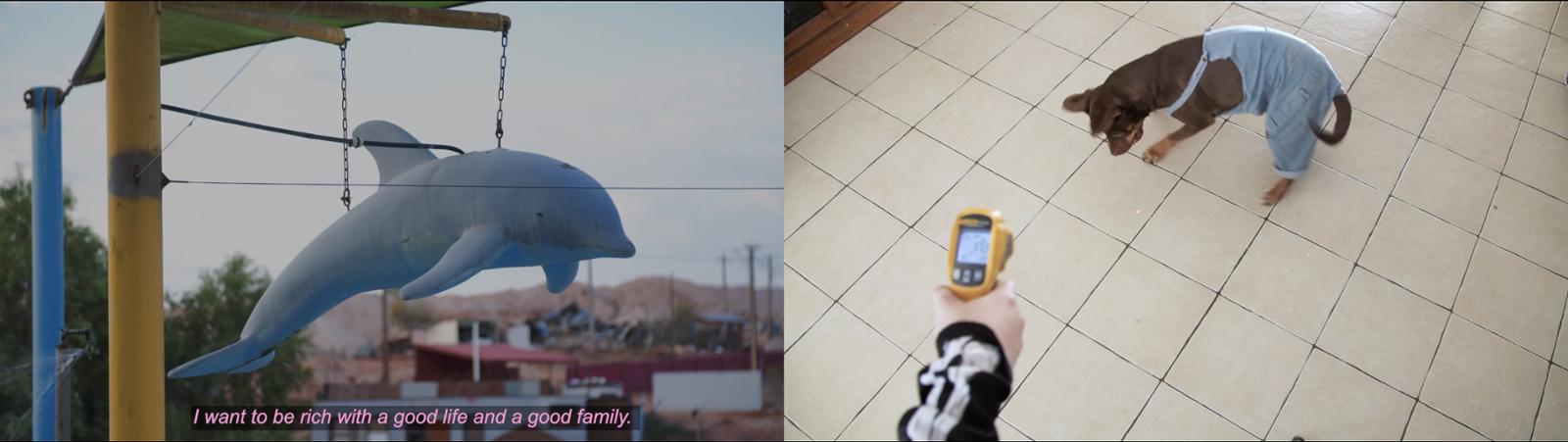

In I take care of what’s mine (2024), Emmaline Zanelli’s two-channel work portrays a fantastical pet-friendly world — a world that isn’t what one might think of Olympic Dam. This is a testament to Zanelli’s long and collaborative methodology, having travelled to Roxby Downs seven times over the course of the project to work with its young people and youth communities. Her brother and cousin were also FIFO workers, a familial connection to Roxby Downs which naturally led her to the social, family and work/life aspects of the town.[3]

It’s a comfy relief to sink into the beanbags stationed at Zanelli’s work, which opens with a quote from Dante’s Inferno and the beautiful things we see on our journey out of hell. We enter the remote town of Roxby Downs, a six-hour drive northwest from Adelaide, led by headlights on a dark road, the silhouette of the town appearing against the red sunset. The soundtrack of squealing saxophone and frenetic drums propels us along, with on-screen text like an adventure role-playing game. Domestic pets are captured in their habitat — fish in their aquatic castles, ducks in their ponds, macaws on shoulders, and a scorpion glowing in the dark. They exist alongside portraits of their young owners in their treasure chest-like bedrooms. With parents and caretakers working long shifts in the mines, these animals become family.

The multichannel screen is not unfamiliar to Zanelli, whose award-winning, three-channel work Dynamic Drills (2019-21) emulated the thrilling feeling of riding a new ‘vehicle’ while she and her grandmother slowly rose up from an adjustable bed. There are strong metaphors in Zanelli’s latest work that elicit similar visceral sensations. As Roxby’s youths drive their cars on one screen, on the adjoining screen we see their journey through the 700-kilometre-long mining tunnels of Olympic Dam. At one point, we are catapulted through an animal tunnel — the POV of a mouse furiously trying to find the exit, the aperture of Dante’s Inferno. The doubling effect of the two-channels becomes more abstract and associative as a young person performs a dance in the blue room of night, while the second screen oozes forth an unknown liquid substance, deep orange like the earth’s crust.

Unable to see inside the mines their parents work in everyday, the youths’ perspective draws from familiar references. For example, the cavity filling foams used in mining is imagined as foaming cream, spewing white from its canister. These creative forms of play prove an effective solution to the myriad legal and ethical frameworks of working with kids. As props and scenography, these everyday materials and objects allude to the greater mysterious and monumental thing they are living next to: the 24/7 mine.

I take care of what’s mine juxtaposes slow-motion high-definition camera work by Liam Somerville with authentic, handheld, grainy footage of daily experience filmed by the young participants. Furthermore, the text throughout the film, developed by Thomas McCammon and Autumn Royal, pushes us further into random associations, sensations and surreal-like dreams. One of the narrators asks their butterfly if ‘she can see my future in her wings.’ Neither complete substitutes for parents, nor everlasting saviours, the non-human animals also have a life and death cycle. But during their time on earth, they provide a glimmer of hope, beauty and guidance for their owners, a temporary star in their life-journey.

The most established of the AFF Expand trio, Susan Norrie has worked extensively in different global contexts. In Japan in 2011, her work Transit was radically changed due to the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which caused the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. Being so close to such a large-scale environmental disaster, she understood the impact of a nuclear catastrophe on the people and the environment. Knowing Fukushima was supplied with uranium from Olympic Dam (the world’s largest deposit of ‘yellow cake’), her interest in this area of South Australia, and the ramifications of the mine, was obvious.

In FALLOUT (2024) Norrie focuses on the impacts of the 1950s and 1960s British nuclear tests at Maralinga and surrounding areas through interviews with Sue Coleman-Haseldine, a Kokatha Elder, and Andrew Starkey, a Kokatha custodian. In contrast to Thorne’s landscape-filled film, Norrie places her subjects directly in front of the camera on location, centring them and their stories. Additionally contrasting with Zanelli’s dialogue-free film (although subtitle-text abounds), we listen directly to their struggles and frustrations over the course of their lifetimes, clearly articulated in these unadorned interviews.

The trust between filmmaker and subjects is paramount here too, developed from shared politics and understanding of Aboriginal Land. Norrie and Starkey met in January 2023 and travelled from Port Augusta to Olympic Dam, Roxby Downs, the Woomera Prohibited Area (WPA) and Ceduna in a total of eight trips. Starkey then introduced her to Sue Coleman-Haseldine. They both have had direct experience of the impact of the British nuclear tests on their family members and on the destruction of their land.

The film reflects these relationships, as Norrie acknowledges, ‘I have been involved in trust that builds over time and the reality that one keeps on coming back to talk more, to understand more, seems to be an important aspect of my work.’[4]

FALLOUT's narrative intercuts between both subjects and their locations. Starkey is filmed at Lake Hart North in the WPA, a fabricated site based on a structure from Afghanistan, and at the Fire Protection Base, a fabricated site based on a structure from the Vietnam War. Coleman-Haseldine is filmed at the Community Sport Centre — a contaminated building brought from Maralinga. She tells us it's in close proximity to the school and kindy where the kids go every day.

The fallout of the Maralinga nuclear tests has often been described as a black cloud that covered the land and people. Starkey tells us it fell on the sheep, and speculates the width and breadth of its reach through the sheep’s circulation in the food chain and distribution of wool.

As is so common, lack of consultation with First Nations people by industrial and mining companies has resulted in the Kokatha and surrounding Indigenous communities still being negatively affected today. In Ceduna, about 400 kilometres from Maralinga, high death rates from cancers, thyroid and heart problems are believed to be caused by the British nuclear radiation decades ago. It is hard to fathom the extent of nuclear radiation, spanning geography, living organisms of all kinds; time does not conceal but rather keeps revealing these impacts. These testimonial interviews are a warning to future generations of the risks of working with such corporations, and of taking ‘consultation’ at face-value.

The expansiveness of moving-image technologies allows artists to mix various documentary, narrative, and audio-visual techniques and styles, challenging easy categorisation. The hardest balancing act may be more about managing collaborators, handling working relationships and allowing creativity to thrive. These artists also bear a big responsibility to represent and respect the people and the land that they have filmed.

The impending doom around uranium mining, and nuclear power which is being championed by the current opposition leader, Peter Dutton, often leaves us feeling helpless. Yet the connection to land and people in each work at Samstag reveals a strength in humanity, imagination and spirituality by illustrating the invisible. However, the works also raise further troubling questions: How will we remember this land in twenty, 50 or 100 years time? How long will it take for things to change, and will they be for the better? How long do we have before another nuclear disaster? What irrevocable damage is being done as we fuel the world? Have we learnt anything from the past? As Andrew Starkey states to Norrie’s camera: ‘Last thing we want is for the [uranium extracted] to be used to kill people.’

Footnotes

- ^ Matthew Thorne, email interview with author, 21 October 2024.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Emmaline Zanelli, ‘Olympic Village’, PH Museum, https://phmuseum.com/projects/olympic-village

- ^ Susan Norrie, email interview with author, 15 October 2024.

_card.jpg)