Local colour: Dyeing and women’s wealth

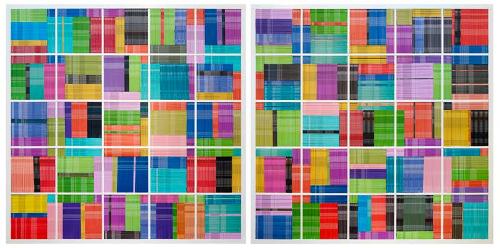

In retrospect, perhaps I imagined it. These fugitive perfumes—earthy, humid, slightly vegetal—were an olfactory epiphany, possibly even a synaesthetic moment. I was visiting Local Colour: Experiments in Nature at the UNSW Galleries in Sydney’s Paddington, surrounded by floating lengths of cloth, a brace of Aboriginal baskets, a row of tiny weavings. Gentle and understated, Local Colour was nevertheless a powerful sensory experience. It addressed the twinned subtlety and intensity of natural dyes married to cloth and fibre, ancient practices being revisited and revised today. Contemporary artists and community-based artisans with generations of knowledge are everywhere experimenting with natural alternatives to industrial chemical dyes and addressing urgent questions of environmental sustainability.