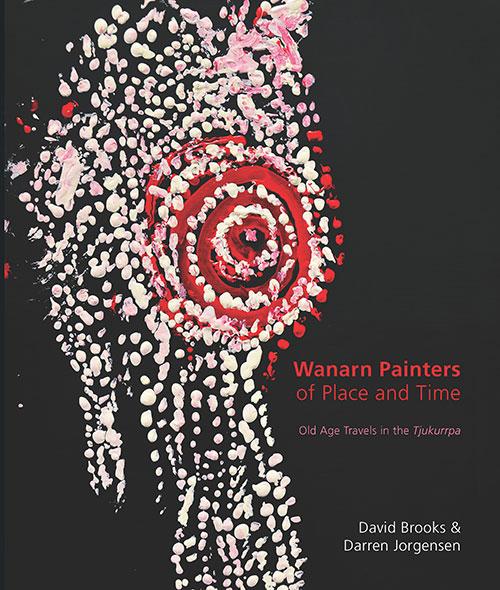

While the mid-twentieth century feud between art and anthropology over the same object of desire, Aboriginal art, still reverberates in some quarters, a productive tension between the two has animated discussions on the subject. A good example is The Wanarn Painters of Place and Time: Old Age Travels in the Tjukurrpa. Jointly authored by an anthropologist, David Brooks, and art historian Darren Jorgensen, anthropological insights add a depth to its art historiography, and art historiography provides an edge to its anthropology.

This short book shows how good these two disciplines are for each other. I read it in one session and it felt like a classic – a complete and singular vision, and a new way to think through Aboriginal art. With only 20,000 words it struggles to fully take us there. But it does point the way, which is also perhaps the vital ingredient of a classic. The book’s success in part derives from its interdisciplinary reach beyond the discipline-specific themes and tropes of anthropology and art history to ones they share, such as philosophy, the psychology of old age and ruminations on relationships between universal and culturally specific aspects of culture.

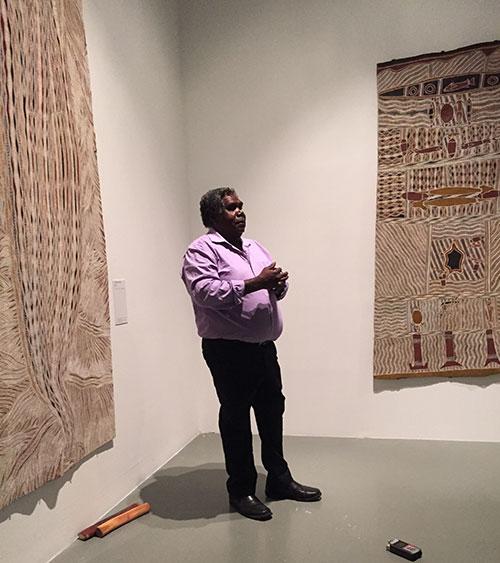

These themes allowed for an inaudible shifting of gears between the disciplines: the fracture between the two disciplines is relatively seamless despite the tropes of each being easily discerned. More importantly, they added new dimensions or layers to the book, giving it a depth and sense of purpose beyond its apparent innocuous subject: art made at an Indigenous aged-care facility in remote Australia, most of it by little- known and in some cases unknown artists.

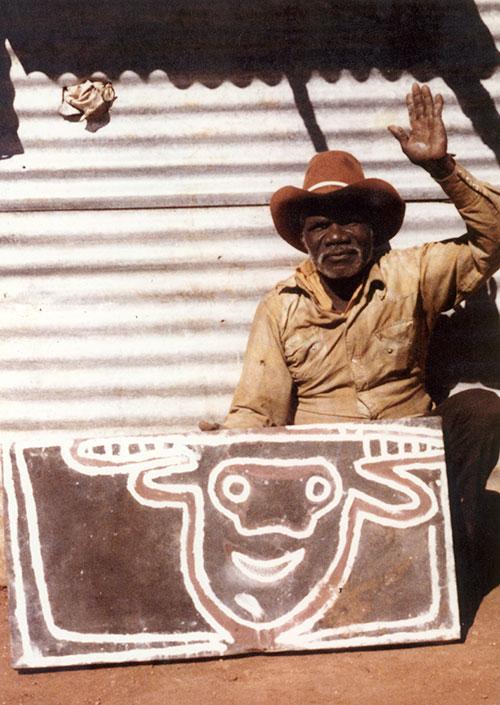

Despite its subject, Wanarn Painters is not about art therapy, which is the main purpose of art programs in aged-care facilities. Rather it addresses deeper existential questions about what drives Indigenous people to paint. The only artist (I know of) ever to commence and conduct a highly successful career entirely from an old person’s home is the Mornington Island artist Sally Gabori. This book is not about her, but it goes some way to explaining what drove Gabori – who had never painted before – and what gave her the energy to paint so many large and vigorous paintings. Her works have their wobbly moments but by comparison the works discussed here tend to be much smaller and more rickety affairs – not tentative but thoroughly shaky. Some might even think them bad Aboriginal art, so rough is their manufacture.

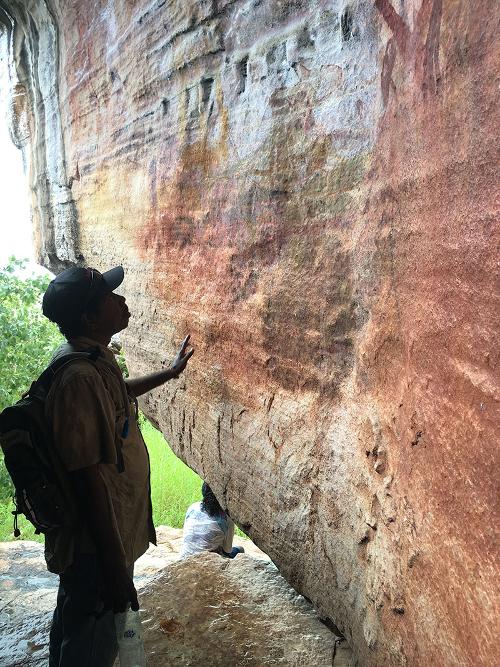

In putting a range of seemingly disparate ideas into a new Gestalt, Wanarn Painters casts new light on conventional understandings of Aboriginal art. While a classic must do this, it must also, as this book does, welcome and even seduce the reader into its flow as if a third participant in its conversation. It is not a perfect book. Like looking out the window of a speeding train, some views too quickly race by. Yet there are recurring features in the landscape, the most intriguing being the examination of tjukurrpa. Brooks and Jorgensen chase it here and there in all its twists and turns, and we follow just as eagerly. In this chase, essential aspects of Aboriginal cosmology are revealed: it is a purely existential thing without essence; it comes into being only in its performance; it is not so much a mythography (Dreaming narratives) or a set of rules (law) – the usual explanations – but a way of what the authors call “tjukurrpa-thinking”.

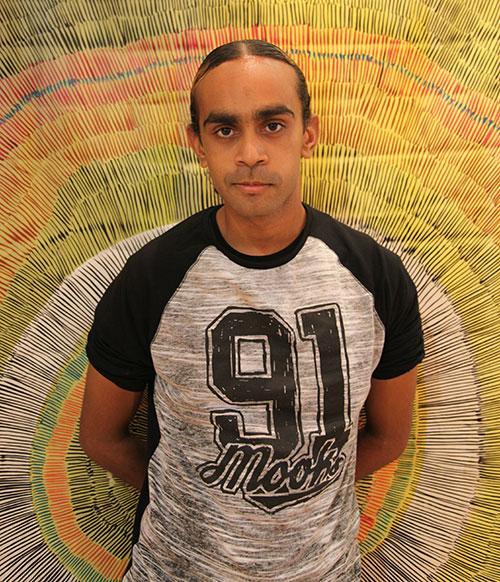

Brooks is an experienced anthropologist with an intimate knowledge of the Ngaanyatjarra people who are residents of the Wanarn Aged Care Facility. Jorgensen is a new generation art historian who accidently landed in the discipline from science fiction studies (in which he did his PhD). He has already contributed a new term, “wobbly”, which names the style of the many old artists who feature in the Aboriginal contemporary art movement, of which a particularly wobbly contingent is the subject of this book.

While admitting that the wobbliness of old people’s art is due to “the necessity of expression that comes with weary limbs and fading minds”, this does not satisfy the authors. Seeking more, the authors – and I suspect Jorgensen is the lead figure here – are not afraid to compare the Aboriginal artists to their Western counterparts, which also has its famed wobblies. They might be few but they are amongst its masters. Examples given are Titian, Rembrandt, Turner, Cezanne and Monet, each celebrated for his late wobbly style. But as the authors point out, this celebration is a modern phenomenon, as if their very wobbliness strikes a chord with how being in the world is experienced today.

The authors’ argument falters somewhat in this comparison in an examination of the details. Cezanne died at the age of 67, which hardly qualifies him for this elect group, and Matisse (who died bed-ridden aged 84) is given as a counter-example, providing the exception that proves the rule as his final paper cut outs are celebrated for their vigour rather than decrepitude. “Instead of the [Aboriginal] artists overcoming their age with new discoveries” like Matisse, Brooks and Jorgensen write, “at Wanarn age remains victorious”.

By implication, the victory is that of tjukurrpa and the earth calling their bodies back from the world their lives had made. And one of Matisse’s last works, the Stations of the Cross mural at the Venice Chapel, is a classic wobbly. Further, the Western wobblies are celebrated for the vigour of their vision and innovation. A similar vigour of vision and intellect is tjukurrpa in full flight in the Wanarn paintings that are also, ironically, all the more apparent for their wobbliness, as if tjukurrpa is never so evident as in this falling or crumbling body.

The main achievement of this book is to transform what initially was a descriptive term for a foundational concept in art history – style, as philosophical discourse. The fragmenting and disintegration of the body as it approaches death, indexed in the wobbly style of aged painters, reveals an essential quality of tjukurrpa – that it has always been molten and in flux. Such art, Brooks and Jorgensen argue, is less about specific tjukurrpa stories and more about the being of tjukurrpa, of how it appears or becomes. Thus they elevate the apparently subjective contingent character of wobbliness as a style into a metaphysical proposition about the nature of being.

The effect of this argument is to give the utmost agency to these elderly artists who, after a lifetime of battling the worldly forces of colonisation and modernity, now face death. Thus Brooks and Jorgensen dismiss Elizabeth Grosz’s relatively popular Deleuzian and romantic excursion into Indigenous art, Chaos, Territory, Art (2008): Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth, arguing that its assumptions of Indigenous anthropological deterritorialisation are too quickly made. It’s a good point but one that might have been pushed further given Deleuze and Guattari’s rather liberal approach to the concept. Do these wobbly paintings evoke, in a metaphysical sense, an absolute deterritorialisation? Or is their imminent return to tjukurrpa a reterritorialisation? Instead Brooks and Jorgensen turn to Heidegger’s metaphysics, arguing that tjukurrpa is the unconcealing of Earth. Indeed, their account of tjukurrpa echoes Heidegger: “to ask any metaphysical question, the questioner as such must also be present in the question” (Heidegger, What is Metaphysics). But if I were Heidegger I would have used Norman Lyon’s Kularta (2010), illustrated on page nine, rather than Van Gogh’s Shoes (1886), to investigate the metaphysical origins of art.

There is much more to this book than the metaphysics of wobbly paintings by old people, if only because metaphysics, as Heidegger also insisted, is always about everything. A sub-theme of the book is gender, and the authors – here I suspect Brooks is leading the argument – proffer an interesting theory on why women dominate Indigenous contemporary art production in remote Australia. As well, there is a fascinating if abbreviated account of the little-known history of these southern parts of the Western desert, including even lesser known early examples of watercolour and acrylic painting before the contemporary art movement in these parts got under way. Besides their historical value, these accounts emphasise the agency of the artists. Of most value from an art historian’s perspective is the attention given to individual artists and their paintings: it provides insights into not just their individual practices but also into the nuances of Indigenous life and the extraordinary diversity that exists in how Indigenous people come to know and articulate tjukurrpa thinking, as if, against the grain of common belief, tjukurrpa is highly individualised.

The book is well illustrated with fifty images, and their order has its own narrative, proceeding from wobbly to a reterritorialisation of sorts and then back to wobbly, ending with a final whimper – these lines of bare existence marking the coordinates of first and last consciousness. My major complaint about this otherwise elegantly produced book is that it lacks a list of illustrations, lessening the importance of the artists and their works. Such big ideas would also have a greater afterlife if supported by an index.